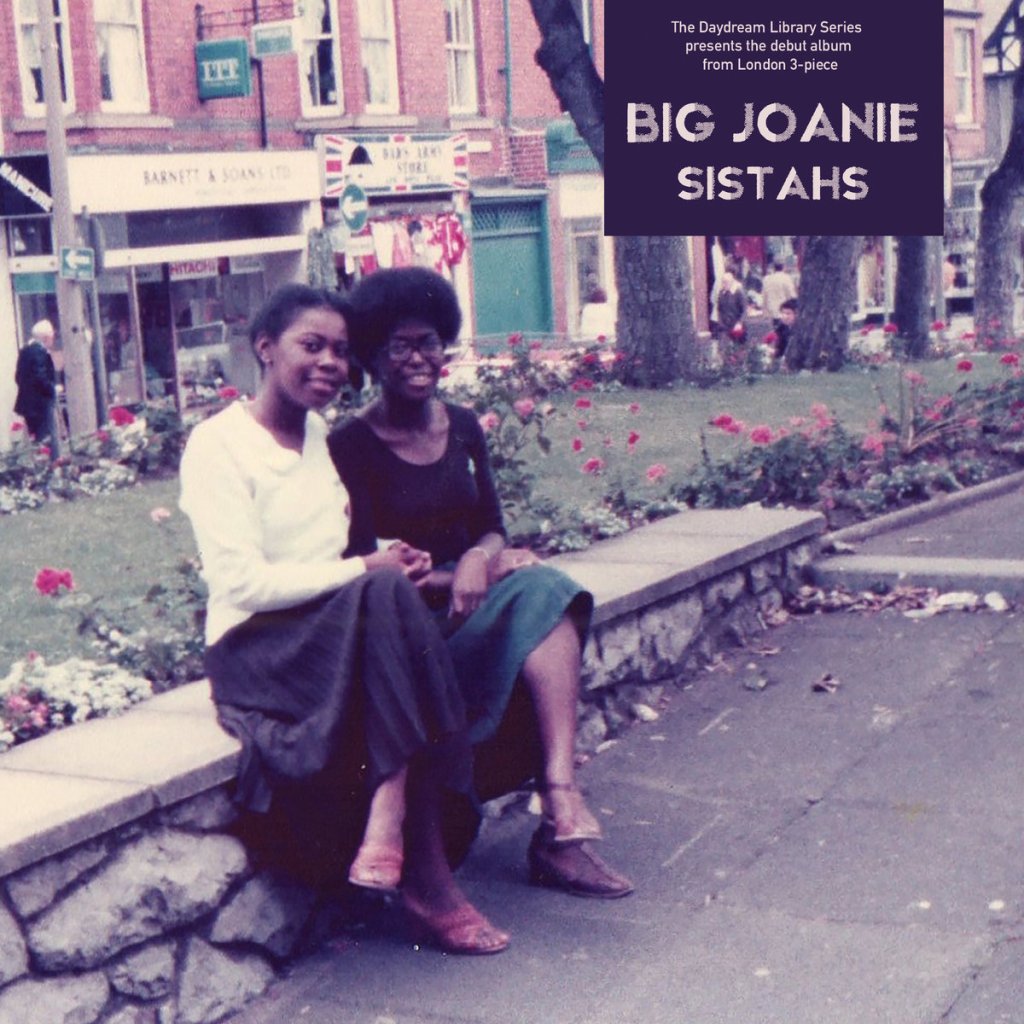

Big Joanie are a Black Feminist Sistah Punk band from London and one of the newest addition to the Kill Rock Stars label. To celebrate their signing they’re releasing a split 7-inch with on KRS with Charmpit and are working on a new album for release in 2021, following up their acclaimed 2018 record Sistahs. Gimmie’s editor interviewed guitarist-vocalist Stephanie Phillips for her book, Conversations with Punx – featuring in-depth interviews with individuals from bands Ramones, DEVO, X-Ray Spex, Blondie, The Distillers, The Bags, Bikini Kill, The Slits, Black Flag, Bad Brains, Fugazi, Crass, The Slits, Subhumans, Le Butcherettes, The Avengers, Night Birds, X, and more. Coming soon! Follow @gimmiegimmiegimmiezine for updates – we wanted to share some of the interview early here with you.

STEPHANIE PHILLIPS: I remember when I first found Poly Styrne, it was a really opening moment it was so weird to find out there was this Black girl doing all of this stuff in London in the ‘70s. Finding her when I was a teenager was really important for me.

Same! I had that same feeling all the way over here in Australia. You listen to the lyrics that she writes, she’s such an amazing writer and creative person.

SP: Yeah, yeah. I’ve spoken to her daughter [Celeste Bell] at Decolonise Fest. I really enjoy her work, it’s miles ahead of everyone else at that time.

Why is music important to you?

SP: It was always my first mode of expression, it always allowed me to connect emotionally with the world in a way that I couldn’t really get through other outlets. Music allowed me to envision an idea of myself that was based on the people that I really loved. I really loved Yeah Yeah Yeahs so I could imagine myself as Karen O, imagine myself having that kind of confidence. I loved The Distillers and wanted to be Brody Dalle. It was like living my dreams through these different frontwoman.

I think we all have wanted to be Brody Dalle!

SP: Yeah!

Did you grow up in a musical household? Did you always have music around?

SP: No, not really – my dad sometimes had some reggae CDs – it wasn’t really that musical. The only thing is that my brother could sometimes play the keyboard or play trumpet at school but he didn’t really pick those up. It’s really just the kind of thing that I was interested in and wanted to pursue on my own really, it was my own hobby. I would go through music magazines and look at new bands, find new CDs. Eventually I asked my mum to buy me a guitar for my sixteenth birthday and I started learning and playing Riot Grrrl songs on the guitar, that’s how I started.

When you found Riot Grrrl did that open up new stuff for you as well?

SP: Yeah, definitely because I guess that was my first introduction to feminism; that was my first introduction to using music as politics and enacting politics through your art. It was really important to have those kind of role models at that time because even though I was quite a shy teenager it was nice to have some place where I could find that outlet for expression and anger, everything like that. It reminded me that even though the world was a bit weird… growing up there was someone that thought like me somewhere in the world and there were other people that listened to the bands like me, it wasn’t that unusual at all.

What inspired you to start Big Joanie?

SP: When I started Big Joanie I was already in a feminist punk band. I was in the London punk scene but it felt very, very white at that time. There wasn’t really any conversation about race or racism or white privilege or anything around that. I was sick of being in punk spaces and having community there and then going to my Black Feminist meetings, different anti-racist meetings and having a community there but never having them meet up, never having them link up. A lot of what I’ve done over the years is working through finding community and creating community. I knew that there was no way that I was the only Black girl that liked punk, I thought there must be someone else. It was something that I wanted to do, to have a band that was of Black punks. I didn’t really envision how long it would last but I just wanted it to happen at some point.

When I saw an advert for “First Timers” on Facebook, which was a gig where everyone plays their first gig as a band and everyone has to be playing something different to what they’d usually play or playing a new instrument, it’s a great opportunity to start a new band. I put a shout out on social media and found our drummer Chardine [Taylor-Stone] and our original bassist Kiera [Coward-Deyell]. We got playing and we played First Timers and at that gig we got a second gig and we just keep going, that was in 2013, it was a long time ago.

First Timers sounds like a really cool thing. When you’re playing there, everyone is on the same level, like you said, everyone is starting a new band or playing a new instrument. It sounds like a really encouraging kind of space and concept.

SP: Yeah, that’s definitely the idea. They’re still doing them now. The idea is that the crowd is as welcoming for you as you would need them to be on your first gig. It’s trying to get more marginalized people to start bands and get involved in DIY culture. For our gig it was really welcoming and inclusive. People were ready to hear whatever you created because they knew you only just started a few months ago, it was meant to be quite haphazard and rickety, that was the whole point, you don’t really know what you’re going to hear. I still go to First Timers gigs when I can now, it’s always a really fun event and really heart-warming.

I wish we had one of those here.

SP: It’s one of those DIY punk things that someone starts it and then maybe someone will start its somewhere else, there’s no copyright on it.

Last week you were really busy; I’m assuming it was with Decolonise Fest that you do?

SP: Yeah, yeah. We’re part of the Decolonise Fest Collective. We had an online version of our annual festival last week, it was quite a new thing for us. We were busy trying to organise everything, get it all ready, because it was running for a whole week. It went really well and we really enjoyed working in this new format. It’s kind of weird to have a festival online, I guess that’s where we are today.

I imagine it would allow more people to participate in it as well?

SP: Yeah. It was more a global audience. People often have said they can’t always get to London or they’re in a different country but have heard about us but they’ve never been able to get to the UK. Having it online has shown a lot more people that Decolonise Fest exists and shown them what we’re doing.

For people that might not know what Decolonise Fest is; how would you describe it to them?

SP: Decolonise Fest is an annual festival based in London, England and it’s created by and for punks of colour. It’s a festival that’s created to recognise the history of punks of colour, recognise the input that we have made into the genre and to celebrate the punk bands that are around now so we can hopefully inspire more people to create punk bands of tomorrow.

That’s such a great idea. It makes me want to go out and do those kinds of things here in Australia, it would be amazing to have more of that kind of community here. So many times I’d go to a punk show and I’d be the only person of colour there and people would say things like, “It’s so good to have a Black punk or a Brown punk here” meaning me and I’d just be like, what?!

SP: That’s a weird thing to say. The good thing about Decolonise Fest is that we can create a community for punks of colour so you can talk about those weird interactions and create your own space. We want to create the idea that people can set up their own Decolonise Fest, hopefully take our idea and make it their own. Hopefully there could be a Decolonise Fest in Australia and different countries around the world.

I know there must have been many great ideas talked about and experiences shared at this year’s fest; was there anything that stuck with you or something important you learnt from the week?

SP: That people are really open to finding ways to connect and create community. I was worried that having things online would feel too impersonal but it felt like people really wanted to find different ways to chat and connect, and talk in the chat boxes when we stream video on Twitch, be able to start conversations in that way. It’s reaffirmed that what we are doing could create a support network and community for different people.

I wanted to talk about Big Joanie’s songs, your songs; I’ve noticed lyrically a lot of them seemed to talk about love, relationships and the human experience.

SP: Yeah, yeah, I guess so [laughs].

When you write; what’s your process?

SP: It depends, it’s everything in every way. You can start with a guitar riff and then try to find a melody for it and try to mouth words and see what fits. Sometimes I keep lyrics in my phone and sometimes I write them before I write the melody or have the guitar line. It happens in every way possible.

What is writing songs for you?

SP: It’s about the process of writing. I really enjoying not knowing what’s going to happening and surprising yourself—that’s one of the most important things. I don’t set out to write about a particular theme or an idea, you play and see what comes to your mind and circle around the idea and keep going deeper and deeper—you create a stream of consciousness piece of art in a song format.

Do you have any other creative outlets?

SP: No, not really [laughs].

I really love your song ‘How Could You Love Me’ it has a very Ronettes-feeling to it.

SP: Yeah, I was feeling very Ronettes-y.

I love your Ronettes poster on the wall that I can see. It’s the best. They’re the best!

SP: Yeah. I really love The Ronettes, it was quite a big inspiration for the band when we first started, of just really loving those Girl Group harmonies and that feeling and sensation that comes from that era. I guess it’s really hard to recreate because it’s the sensation of people being young and not having any cares really. It so invigorating and interesting, I always want to listen to it and hear what’s going on.

Same! I really love Sister Rosetta Tharpe too! I think people forget or might not even know that she was a pioneer and started playing electric guitar and rock n roll before rock n roll.

SP: Yeah, yeah, exactly! She’s such an interesting guitarist, she kicked that all off. People don’t always know the real history of rock and what was actually involved and going on, they think Elvis [Presley] just did something and the Beatles did something and that’s it.

[Laughter] Yeah! That’s why it’s important to have conversations about these people and to look into history. As well as making music you also do music journalism and interview people.

SP: Yeah. I’m a trained journalist, I started off in journalism first, I’ve been working as a journalist for over a decade.

What attracted you to journalism? Was it telling stories?

SP: I guess, yeah. Telling stories and having the ability to create a narrative is very important and interesting to me. Being able to communicate is really interesting, that’s why I centred a lot of things around writing in that way. I wanted to write music journalism because I was interested in music. I wanted to be involved in it in every way, that’s why I’ve done everything [laughs].

I know that feeling. I first had the feeling when I was a teenager and there were so many great bands in my area and all the music papers and magazines weren’t covering them and I got a zine from a friend and had the realisation I can do this! I went straight to my bedroom, started listening to music and started to write my own zine. From there it keep going and I haven’t stopped.

SP: That’s amazing! I haven’t made my own zine yet but I love the idea of zine culture, creating your own platform, surpassing the usual kind of press and publishing industry, it’s really interesting.

The way that the music magazine/publishing industry works, I hate it! I don’t really care for the music industry either. I like existing on the outside of that. I find things to be the most exciting not in there but on the fringes where people can totally just express themselves without censorship or compromise—creating your own community is far more exciting to me.

SP: Yeah, definitely. That’s where things start. There’s so much going on… I think about the scenes that I’ve been involved in in the UK, they’re hardly ever reported about but there’s just so much interesting music being created here, there’s so much interning music being created in what feels like predominately female and queer punk scene as well. If you looked at the average music press or what is being reported as the “band of the moment” you would think its all CIS straight white guys. That isn’t whose making the most forward-thinking music today… it’s not white men [laughs].

I’d love to read a zine made by you and hear all about what’s happening where you are.

SP: It’s a really interesting music industry here and there’s a lot going on. There’s so many different scenes even though it’s a small island, there’s so many different scenes in London; there’s multiple punk scenes that never actually intercept and never really know about each other. It’s hard to cover it all I feel.

What’s Sistah Punk mean to you?

SP: It was a phrase that we came up with to describe ourselves with for our first gig. They asked us what we wanted to describe ourselves as and we said, Black Feminist Sistah Punk, just because it’s a very literal description; we’re Black punk woman, we’re into punk. It can also be something that people can use to find other Black woman that are into punk and other Black Feminist punks. There weren’t too many women in punk bands in London at that time, we felt like we needed to specifically say that we are Black Feminists because it was important to us and we thought it would be to other people.

It’s still something important to you all these years later?

SP: Yeah. It’s still literal because we’re still Black woman and Black Feminists. It’s still important to declare who you are and who your identity in a world where being a Black woman and being a black Feminist and having an opinion is still not the done thing [laughs]. It’s still important, it’s still punk to be Black and female and opinionated!

Whenever I read interviews with Big Joanie you always get asked about feminism and race; do you ever get tired of speaking about these subjects?

SP: It all depends on the context of the interview. It could be from the context of someone not knowing about feminism and race and just wanting to ask the generic; what’s it like to be a woman in music? What’s it like to be a Black woman in music? That’s not really very interesting because the question is aimed at a white male audience in its nature; it’s trying to open up what’s it like to be a Black woman for people that aren’t Black woman. Is it’s discussing the inherent nature as who we are as individuals and why it’s important for us to talk about ourselves in the way that we talk about ourselves then I don’t mind. It’s about us taking the reins of the conversation and taking control, explicitly stating, what we do and why we do it.

You have a new release out ‘Cranes In the Sky’ a Solange song that’s on Third Man Records and I know as a young person you really loved The White Stripes; how did it feel for you to put out something on Jack White’s label?

SP: I really loved The White Stripes when I was younger, I guess everyone did! I can’t remember what the first record I had was, maybe it was Elephant. The last two years of Big Joanie has been a lot of strange happenings every day, bumping into people that you just read about in magazines and having to be normal people around them because you have to do a job [laughs]. We just bumped into Thurston [Moore] and Eva [Prinz], it was like, oh that’s Thurston from Sonic Youth [laughs] he looks like Thurston, in real life! …which is very strange, I can’t remember the first time I heard Sonic Youth because they were an omnipresent force around all the bands that I liked and listened to, people wrote songs about him. It was weird to imagine that he was a real person.

With Third Man it’s a strange connection between what raised you and what brought you up into the musician that you are today and circling back and meeting those heroes. It’s a really strange experience but we’re really happy that Third Man are interested in putting us out, that they liked the single!

It sounds so amazing! Why did you decide to do the Solange song?

SP: I don’t know if we ever discussed why we’d do it, we all automatically decided to do it one day [laughs]. It was a song that we we’re all listening to and that we loved, everyone we knew was listening to it and connected so deeply to it as an album, because it spoke specifically to the female experience. We thought it would be a fun song for us to cover. It took us a while to figure out what was going on in the song, it’s a weird jazzy song and we don’t do jazz we’re punks [laughs]. When we figured it out I think it became one of our best live songs and people always love it. It’s nice when people recognise it when it gets to the chorus.

Have you been writing new things while at home because of the pandemic and lockdowns?

SP: Yeah. As with most freelancers I didn’t get any furlough, there was a furlough scheme for people who lost their jobs in the UK, I’ve been working all since. I’ve been working on a book on Solange Knowles, I’ve finished that now and it will be out next year. I’ve been writing lots for different places, different music magazines, content writing, those kinds of things.

What’s something that’s really important to you?

SP: My morals [laughs] and sense of self. As you move into different arenas in life I think you can get tested maybe, there are some things that can through you for a loop. I guess it’s one thing that I’d never want to give up on is my idea of right and wrong and doing things for the best. That’s not always a good way to go into industries like the music industry because there’s going to be a lot of being tested and people trying to brand you and make money off of you; staying strong on that is what I would want to do and what I believe in.

That’s why I’ve stayed on the outside of things and why I’m putting my book out myself. So many times people try to change what it is or they’re only interested in the “big name” people or this or this… I’ve interviewed so many bands and it’s been the first interview they’ve ever done, sometimes that can be the most interesting interview and can have the most interesting ideas.

SP: Yeah, that’s true! You can get a lot from people that are just staring out and need that help or need that conversation with someone like you. That’s the thing, people always go up to people once they reach a certain level and they just forget about everyone underneath. The people coming up are the ones that need more help really.

Please check out: BIG JOANIE. BJ on Facebook. BJ on Instagram. Decolonise Fest. Big Joanie on Kill Rock Stars. Big Joanie at Third Man Records. Check out Stephanie’s writing work.