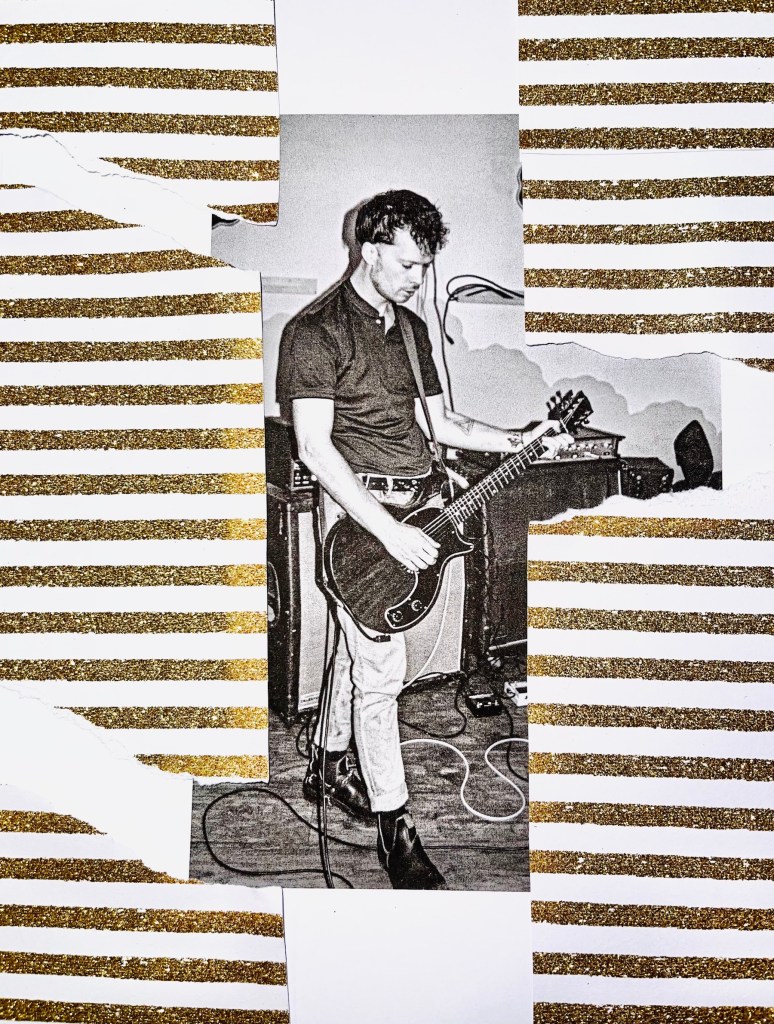

Naarm/Melbourne-based anarchist punk band Punter exploded onto the scene in early 2020 with a scorching demo, released on cassette by hometown label Blow Blood Records. Fronted by vocalist-guitarist Nathan Burns, Punter’s music challenges societal norms, with thought-provoking lyrics. Their 2023 self-titled debut full-length quickly became a staple on the Gimmie turntable, offering an eclectic mix of songs that delve into anxiety, fear, death, grief, boredom, and class politics. We caught up with Nathan just before he left Australia to tour Europe with Punter and travel indefinitely. He’s since explored Greece, the underground catacombs of France, and Spain, with his latest stop being the UK.

NATHAN BURNS: It’s been nonstop since Punter got back from tour with Rat Cage because we’re going on tour in Europe in three days. The space in between two tours is about a month and a half. Two weeks of that are taken up by me, realigning myself and working out who I am again, and adjusting to the fact that I have a lot of shit to do, but it can all happen on my own schedule.

Prior to that, I’ve been working a lot, for about six months, and doing band stuff all day, every day after work. I’ve been floating in a kind of timeless continuum in a way, but it’s full of deadlines in another way. I’m wrapping up my life here as well—moving out of my house and getting rid of my shit. I sold my car. I’m going travelling indefinitely after the tour. So it’s a lot at once, changing stuff.

I read a list recently about stressful events humans go through and death of a loved one, losing a job, and moving house or country, were all up near the top of it. So much is happening for you right now.

No one in my family or immediate friendship group has died recently, but you’re on the periphery and it’s always going to be constant once you get to my age, 30. It’s funny, these nexuses where everything happens at once. All that energy.

It’s exciting you’ll be travelling indefinitely. Not a lot of people get to do that. Do you know where you might end up or are you just going to wing it?

I’ll be lurking about in Europe. There’s options for me to get a visa until I’m 36, in France and Denmark. They’ve raised the age in those countries for Australians. In Switzerland, you can maybe get a permit to stay as an Australian now. It’s easier than before. I quite like Spain and connected with a few people there. I haven’t sorted out visas or anything yet. It’s all been too manic with the tour stuff, band shit and recording.

Have you been to Europe before?

Yeah, my old band, Scab Eater toured there and I lived there, the cycle is repeating now. I lived in the UK after the Scab Eater tour in 2016 for about a year and hung about there and did little trips to the mainland, to the continent and back. The band had fallen apart over there and I came back here and started Punter. I’m ready to not be in Melbourne anymore.

Why did Scab Eater fall apart?

We did two months of touring; it was stressful for certain members, to be honest with you. I felt like I was living the dream, but there was definitely struggling to cope with two months and 50 shows. We tried to tee up some other gigs in the summer, a year later from there, but by that point, a lot of people’s plans had changed, and we bailed on those gigs, which was pretty embarrassing, as far as I’m concerned. It had gotten pretty dysfunctional as a group. It can be really stressful when people are out on the road; you’re in such close quarters, and you’re basically living with each other the whole time. It can be really stressful for them. We pushed it further and further and further until we found out where our limit was.

Did that experience affect how you do things now with Punter?

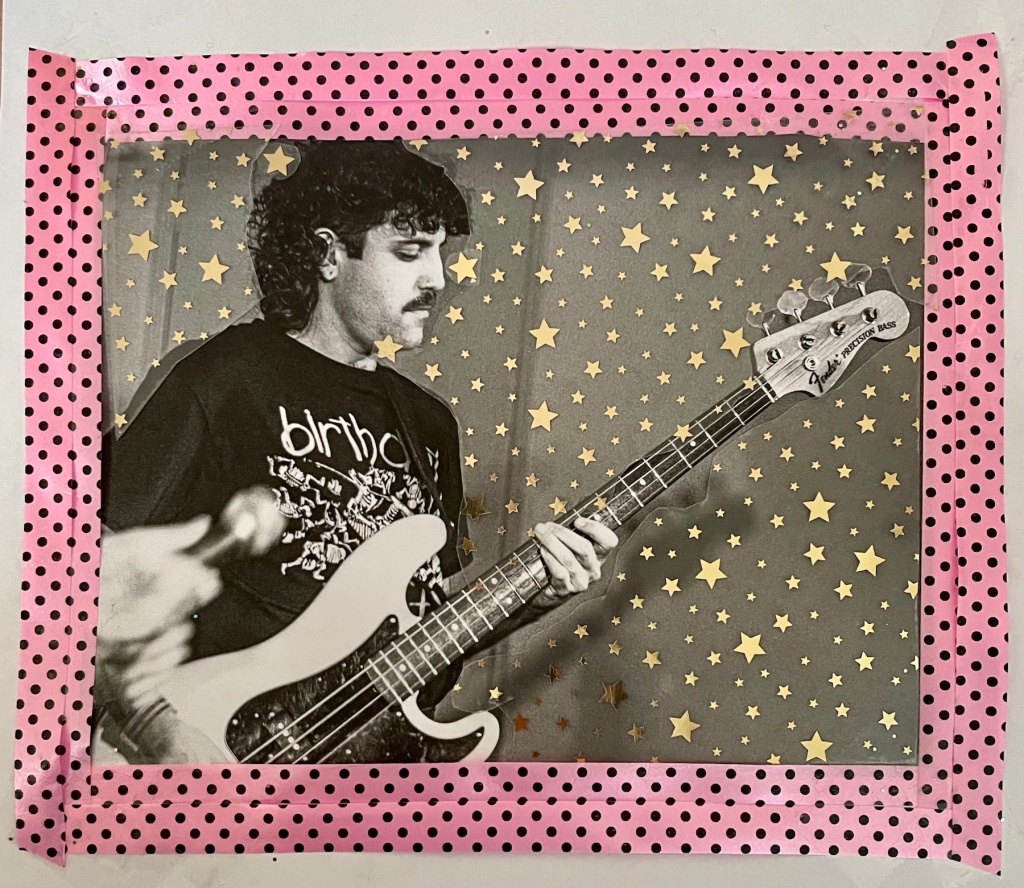

Kind of. The personalities are slightly different with us. It’s a bit different playing in a three-piece. Jake, who played drums in Scab Eater, is also the drummer of Punter. In that way, we have that dynamic still as old friends. Then there’s just one other person, Bella, the bass player.

Scab Eater was a big rowdy boys club, and we’d fight like brothers, argue and be really stupid little boys together. You bounce off each other. With Punter, things are more chill; there’s less huge personality stuff and egos bashing their heads against each other. There’s probably more drinking and a bit less adventure as a group.

And I’m certain that although we are about to go on tour for a month in Europe, I don’t think two months on the road would ever be on the cards for this band like it was for Scab Eater. Everyone were travellers in that band, either on the dole or people were on their big holiday to Australia from the States. There was a lot of transients with that band. The other members of Punter are pretty settled in Melbourne for the time being.

What do you enjoy about travel? The adventure?

Absolutely. That’s what I’m in it for. I always want to improve myself through it somehow. It’s very easy to walk around sticking your beak into other societies and going, ‘Oh, that’s pretty, isn’t it? Oh, you’re pretty poor, aren’t you?’ Or how does that feel? And then you kind of get disillusioned. But the aim of long-term travel is to seek experiences that improve you as a person or connect you with other people you can learn from or offer what you have—skills, wisdom, or experience in an area—to whoever you meet along the way.

I enjoy that about travel too. You can actually see how other people live their lives firsthand. Lots of places in the world are very different to Australia.

Yeah. There’s a fair bit of phobia that sort of infected Melbourne society, particularly in the last few years. In the punk scene, I’ve noticed a distinct lack of traveling punks or whoever coming through and being put up by people here.

When I was a teenager, let’s say like 14 years ago, I was hanging out at a big punk house, and there’d be six Europeans that had come through for the first half of summer and then another six had come through the other half, and they’d all crash on the floor or the couch. Everyone was constantly meeting people from different parts of the world. That exchange felt really vital to me because it showed us, our little squat in the suburbs, that if we ever went overseas, there was this whole network of people that we could connect with, and that gave us mobility for travel in the other side of the world.

Hearing people’s stories was inspiring. Learning about the ways in which we differ because of where we come from was also really important. I don’t see as much of it anymore. It’s very easy to feel daunted by the experience because it’s almost like that culture is really not in my sphere anymore and certainly not really in the punk culture that I’m a part of here right now.

Is there anything that you like like about European culture that’s different from here?

It’s hard to say without coming off slightly insensitive because there are so many little cultures. Broadly, I guess what interests me with Europe is a twofold thing that’s sociopolitical. In that, it’s not colonised land in the way that we think of it being colonised land here in Australia. It’s also a place that has experienced vast amounts of political turmoil and change in the time in which Australia has been a British colony.

So, the average person there, between them and their parents, in certain countries, may have experienced really radical political change from regime to regime, to democracy, to fascism, or whatever you’ve got, within 60 years or something. They really have an ingrained understanding that politics matters. It affects your life, and it affects everyone, and that there are certain things worth fighting for.

I don’t think it’s as easy for Australians as a whole to feel passionate about political change because we’ve pretty much never seen one since the British came. There’s definitely things that we benefit from as workers or whatever, like the union movement from the 50s through the 80s, that now has resulted in quite high wages for certain parts of working-class society. There’s this narrative there. There’s the Eureka stockade. There’s all this stuff, but the system has remained the same, and its goals have remained the same. The exploitation of the country and the society that has resulted from that have remained the same. It’s very hard for us to imagine something being different, and there’s a lack of imagination there.

To go on a little bit, the struggle against capitalism or the state or whoever it is at the time that the people have essentially mobilised against in a popular movement, like right now, it’s in France. It’s [Emmanuel] Macron because he’s raised the retirement age. Those struggles are uncomplicated by this extra element we have here, where the European descent people or other migrant families that have come since, we have to fight for our rights as working-class citizens, or let’s say, working to middle-class citizens, anyone who’s not part of the elite. We have to fight for change.

But we also have to keep in mind that it’s not our country and that there’s this underneath that struggle, that shit’s the tip of the iceberg. That decolonisation is this huge other part of it that we have to learn to unpick as people who aren’t First Nations people. We have to work all that out and work out how that relates to our goals. A lot of our goals, let’s just say, like white activists or whoever, might have more of a relationship to things that we actually don’t like about colonisation than we admit.

And that’s saying we want the political change that we see in Europe. We want the radical political, we want their type of socialism or anarchism or socialist democracy. But to want that stuff here could be, at points, in direct opposition to what decolonisation actually means for First Nations people in Australia. In Europe, it’s likely that the movement is always going to be a bit more straightforward, and we’ve got a lot more to try and work through and learn here.

As a First Nations person, I know that many of us have immense intergenerational trauma that filters through everything, in ways that you wouldn’t even think it does.

My grandfather lived in a time where after 4 PM and on Sundays, Aboriginal people were forced to vacate the town centre beyond the boundary posts; this wasn’t even that long ago really. The society that he lived in made it seem shameful to be Aboriginal. A lot has changed but it’s such a complex and hard thing trying to navigate and process—to just exist. Being a First Nations person, just existing can be a political act. Everything you do is so often looked at and scrutinised.

It must be hard knowing that that’s the stage where it’s at, because that’s a long road from simply just existing.

It can be. Every time I walk out the door, I have so much to think about and protect myself from.

What was your first introduction to punk?

Superficially, my first introduction to punk would have been borrowing a Good Charlotte CD from the library when I was about 11. The lady at the library was like, ‘Oh, that’s that punk rock band, isn’t it?’ I was like, ‘I guess, maybe it is.’

Then I wound up in Borders Books one time. They had CDs and CD players on the wall that you could sample your CD with the little scanner and play what was on there. I found all these CDs, like the Punk-o-Rama compilations and Rock Against Bush CDs. I was pretty into all that pop-punk and ’90s skate-punk stuff. Through those compilations, I was exposed to a great variety of things that were happening in the mainstream. There was stuff on there, like Madball, which for 15 years, ever since, I’ve been like, ‘This just keeps getting better the more I listen to it.’

I liked all that kind of stuff until I was about 16 and wound up going to shows, finding out about gigs through meeting people around the neighbourhood. I grew up in Brunswick, which through the 2000s was the place where you went and lived if you were a punk on the dole because it was cheap. You could afford to live there. Back then, it was a rundown, working-class neighbourhood, and there were heaps of abandoned buildings everywhere, so everyone was squatting. There were lots of parties happening all the time in them.

I went to school across the road from a block of squatted warehouses; they were all artist warehouses that weren’t all even necessarily punk. There were unicycle-riding, circus-hippie types and all that kind of stuff. You’d run into people, and that sort of autonomous, anarcho-punk culture was right there. Anything else like hardcore or metal was all happening between Brunswick and the city too. I was very lucky geographically. It was a really exciting time.

At some point, I realised when I was 18, ‘Oh, shit, I think this is actually better than most places. We’re kicking ass over here in Melbourne.’ It’s not the same anymore; it’s more expensive to live there.

How did you learn to play guitar?

I had the benefit of guitar lessons through school when I was about eight. Like your foot on the stand and reading the music off the page. That kept going until I was like 12 and I was starting to try and learn a bit of flamenco. About then was when the punk started happening and my folks got me like an electric guitar. I started to learn how to play power chords.

I had a band, some friends at school that we knocked about with when I was about 14. Classical guitar lessons was really important to the way I play now. I learned to be nimble and expressive through that.

I can see that, you have a unique style of playing.

I don’t really know scales and keys very well, standard nuts and bolts. In the last four years I started playing leads. I stopped really being concerned with music theory. As a player, I was in a state of arrested development that I’m only really just emerging from now. It’s this kind of awkward, clunky stage where I think a lot of original sounding things happen by accident.

Are there any songwriters that are inspirational to you?

As a child, I was totally into The Living End. The sort of songwriting conventions that Chris Cheney has, crept into my songwriting decisions. There’s a lot of changes from minor bar chords to major ones.

Also, AC/DC and The Clash. When I was about 18, I was obsessed with Tom Waits. Hard to say how much of that ended up in my music, but I spent, endless hours with Tom Waits records.

King Crimson was another. They have an attitude towards creating music in a progressive and original way. Although to compare oneself to the King Crimson is pretty presumptuous. More recently, I became obsessed with The Jam and Paul Weller, his lyrics were observational and depicted scenes as he saw them in a way that said so much about who he was as a person without having to delve into his own personal feelings in an explicit way.

I was attracted to that in Sleaford Mods as well. It’s so accessible and witty. I remember when I was with them a lot around 2015 or 2016, those guys have this way of making everything sound like actual conversation. I’ve strived to replicate that a little bit because I’m good in conversations and not as good as a poet. I try and make the lyrics of a song more like having a conversation with me. I get across what I’m trying to express uninhibited.

Do you think your involvement with punk, helped shape a lot of your political views or how you see the world?

It’s a chicken and egg situation. Yes, it did. Unequivocally, it did. But I was raised in a pretty political family, a decently educated, lefty, middle-class family in Brunswick, so that shit was all around, it was constant. John Howard here’s this guy, he’s on the newspaper, he runs the country, he’s a prick. Every day swearing at the newspaper, this guy’s a prick and he’s in charge. So when you get raised in that kind of environment, I was raised into anti-authoritarianism.

My grandmother on my dad’s side was a Labor politician under government. They were, as a Canberra family, academics and so forth. My dad went on to work as a solicitor in Native Title. So that was obviously something he’d come home and talk about all the time. For what it’s worth, he got terribly jaded by it, which I’ve heard happens to almost every Native Title lawyer. For those that might be reading this, that are new to the concept of Native Title, it’s the attempt by the Victorian or State Government or whoever to resolve disputes between different mobs who claim traditional ownership of the land. The state attempts to mediate between the different groups that lay claim. It’s vastly complicated, obviously, by The Stolen Generations and genocide and who can actually trace their lineage back during all the chaos of what had happened in that time.

And then on top of that, you’re trying to apply the white man’s legal system to this other culture that has their own way of doing things. And since you’ve come in and fucked it up and now you’re going to use your legal system to try and stop them from tearing each other apart over the land that you’re, oh so graciously, giving them back. My dad did that for a bit because he wanted to feel like he was doing a good thing while putting food on the table. He would have tried his darnedest. It sounds really, really hard to me.

The politics in punk appealed to me as a kid because there was already conversations happening in my house all the time. On the other hand, my dad worked for the institutions of government, so I could be a bit like miffed about that if I wanted to on the odd day.

The more I listened to punk music, the more political bands always stuck out to me. Growing up around the sort of autonomous DIY and anarcho-punk stuff informed me on so many things that my parents wouldn’t have really held as their own political beliefs as well.

I noticed in the liner notes for your self-titled album, you mentioned that Punter are Anarchists. What does that mean or what does that look like for you?

Anarchism – there are different sorts of strains of it and different beliefs that people choose to express through that word. But the most pragmatic way to look at it for me is to try and establish a society which is not based upon structural violence or institutions whose sole purpose is to punish or inflict violence on other people.

So the idea is that everything that we’ve created as a society, let’s say, Western society, over the thousands of years, is built to rest on these pillars of enforcement, where the principles of the society must be enforced. That the only way to make things fair and just is to punish the few people that disobey. Institutions that have violence at their core are unnecessary.

From there, you could hope to build a somewhat utopian civilisation whereby people didn’t need to be punished and where bad things probably still happen, but maybe in much less frequent amounts.

In your liner notes you were also talking about, the trauma and the collective trauma, we experienced through the pandemic and lockdowns. Melbourne had the longest, most harshest lockdown out of every everywhere in the world—you mentioned you felt like it changed people’s brains. What were the changes you saw in yourself?

I feel regularly more afraid—not just of the future and what’s going to happen broadly in a political sense or anything like that, but just afraid of taking risks on a day-to-day level. I feel more withdrawn into myself. I feel like the instances where I speak my mind in a confrontational way, maybe where I tell someone what I really think, even though it’s going to be hard to say, have diminished greatly. It’s hard for me to imagine change in my life or the lives of the people around me. You know that thing they say about depression – it’s impossible to envisage happiness or the change that’s going to, step by step, bring you out of that. It seems all-encompassing.

I feel like everyone went through that a little bit. There’s like a fog beyond the city limits here. And because Melbourne’s been such a self-absorbed cultural town anyway for so long, we’ve been up our own ass for ages. Then we got forced into the isolationism of Melbourne and I suppose a lot of people probably just went, well, yeah, that’s alright. What do we need the rest of the country for? Bogans. Whatever.

Do you kind of get tired and overwhelmed by all the shit that’s happening in the world?

Currently that’s the case.

How do you deal with this feelings?

Just try and launch myself into it. That’s what I’m hoping to do when I hit the road after the band does our tour.

Because you’re taking risks? It’s a risk not knowing what will happen or where you’ll go. You’re running headfirst into all these things that you’re afraid of or scared of, and going to do it. That’s a big leap.

I hope so. Look, let’s be honest, there’s definitely been riskier things than an Australian citizen travelling in Europe and having a little holiday that he saved his money up for. But I’m hoping to engage in some risk taking behaviour whilst I’m over there. Hopefully it will make me a more fortified character when I do, because I know I need to break myself out of the rut that I feel I’m in and that I feel like a lot of people that we know down here are in.

European societies, whilst being superficially similar to the Australian society here, it’s different, it’s older, there’s far more people, there’s more poor people. The systems in place for people’s health care are different. A lot of people died during the pandemic and it just gave me a bit of a different perspective on that.

My mother was in a coma in the Royal Melbourne Hospital during the first outbreak of the pandemic. We weren’t allowed to go there for months at a time. She was coming out of it and she’d had a stroke.

I’m so sorry you had to go through that. It must have been brutal nor being able to see her because of COVID. That’s full on.

It was crazy. Obviously when someone in your family is sick or in a health crisis or in the fucking ICU, that’s this whole thing, it takes over your world. Then suddenly the pandemic happened out of nowhere on top of it. It was something that we obviously didn’t really see coming.

Before, you were talking about a fog and depression and not being able to see happiness sometimes; I was wondering, where do you find moments of happiness?

Being able to lose yourself a little bit can be the closest you get. Happiness is probably a bit of a misrepresented overused word. The place that people commonly find happiness is in the arms of their lover. That to me is closest to the definition of happiness. But there’s all these other forms of release that we have and music is a really obvious one that allows us to transcend the happy/sad dichotomy because there’s so much melancholy in happiness, don’t you reckon? Sometimes sad songs make you real happy. When they’re singing about heartbreak or death or grief, all these things like that. Whenever I feel quite happy, there’s always got to be a little bit of a blue note to it, otherwise it wouldn’t be legit.

Jamming is a big one for me. I don’t mean jams in rehearsing the songs from start to finish. Jamming when you’re actually improvising or writing a new song with everyone in the room contributing parts and it’s coming together and everything outside of that room does legitimately go away because you’re building in there.

I tried to take up surfing in the pandemic. I fell off a lot. I was raised boogie boarding, so maybe I had some kind of base layer of knowledge for what waves to take and things like that. Unfortunately, I busted my shoulder, six months into the whole thing. I couldn’t really touch it for another nine months. But floating around on the surfboard just made me feel grouse. It was nice being on the water. That made me really happy.

It makes me happy too. I find Punter songs to be mostly observational. Is there a particular song on your album that’s more personal?

They’re about broader things that we all experience. Look, when you say ‘personal,’ like something that I feel like I’ve really gone through just me… no, not really. I was trying to reach out into the pool of emotions out there amongst me and my peers and just the people of Melbourne. At that time, when we were stuck in Melbourne (where a lot of the lyrics came from), the closest it would get would be on our song ‘Curfew Eternal,’ is about grieving during a time of upheaval or change.

That’s when my mother was in a coma following a stroke or recovering from the stroke. It’s a bit of a blur. There were moments in which we didn’t know if she was going to survive or if she would want to survive, if that was available to her.

That song, whilst being set against the backdrop of the pandemic and lockdown, was really about these golden clichés – like embracing life and seizing the day – and trying to say that we’re heading into an era of increasing social instability. The powers that be are going to try and do whatever they can to make you feel like you cannot take risks. The greatest risk that you can take is to express solidarity with the other people in your community, and that as soon as you do that, you are giving up your only opportunities to make money and achieve security for yourself.

The song is desperately trying to push back against that concept and say that the only hope that we have is to constantly throw our lives into turmoil together to try and make it through and to push back against all authoritarianism. The really severe brand of authoritarianism that I feel is looming in the not too distant technocracy that’s coming quite soon.

I’ve always, like my parents were, been very anti-authoritarian too. Most people teach their kids that if something goes wrong, police are there to help you, well, my parents were always like, ‘Don’t trust cops.’

My parents eventually developed that position after I got arrested enough and they had to deal with them. But before that, it was very much like, oh, you know, the cops are all right, the Salvos are all right. They’re trying to do what they can.

What did you get arrested for?

Kid things; graffiti or drinking. There was a couple of instances where I was involved in direct action stuff that wound up in criminal damage cases and stuff. I was in court. But generally just getting picked up by the cops and my parents would get called up.

Around 2015, wasn’t Scab Eater in the news in connection to an ANZAC War Memorial being graffiti? How was that time for you?

I’ll start by saying my parents were not particularly phased after everything they’d already gone through up until that point. That time, I’ll be quite honest here and say that it was terribly exciting for me, having grown up as a punk rocker as a little boy, as a teenager, and getting into the really up-against-the-system kind of political punk stuff. Suddenly I was public enemy number one. I felt great…

It was a good opportunity for the scene to have an argument with itself because there were so many people who were way more offended than they should have been. Also, a lot of really reasonable people that got to pick it apart for what it was.

It was a thing that happened in response to the 100 Years Centenary of ANZAC, which at that time was everywhere. They spent more money somehow on the 100 Years Anniversary in terms of billboards and bus stop advertisements, like ramming this glorious soldier shit down your throat. At some point, there was going to be this sentiment expressed in one way or another. These ANZAC memorials get defaced every year; this just had the band name on it.

Regardless of your opinion on the Australian Government or the Allies, or what’s become of the world since World War II, or whether or not we should have been involved going into World War I and II, it was deeply unpopular with working-class people. It was divisive. It wasn’t this one-sided thing where the working class all went off to war and then people like me, 100 years later, shat on them for it.

ANZAC was invented to stir up patriotism and militaristic patriotism at that. There was a lot of debate about how much money should actually be spent on it—millions and millions every year. It’s this huge amount of money for people to glorify stuff that we shouldn’t have been doing. There’s a way to still grieve the exploited people that wound up being tricked into going to war and killing each other. Everyone should just listen to Discharge on that day [laughs].

How was your show last night?

It was killer. It was a mixed bill. Over 100 people through the door on on a mixed bill always feels like a success.

We love mixed bills!

They’re always so under-attended. This is the only reason that all bills are not mixed because people know that they’ll get a crowd with five things that are the same thing. It’s a commercial decision every time you see it. And that’s the kind of artistic landscape, the heavy-handed over regulation of live music creates, less mixed bills in the city of Melbourne. What the fuck is that?

Punter’s self-titled album is out via Drunken Sailor Records (EU) and Active Dero in (AUS/NZ) – GET it here. Punter have no socials.