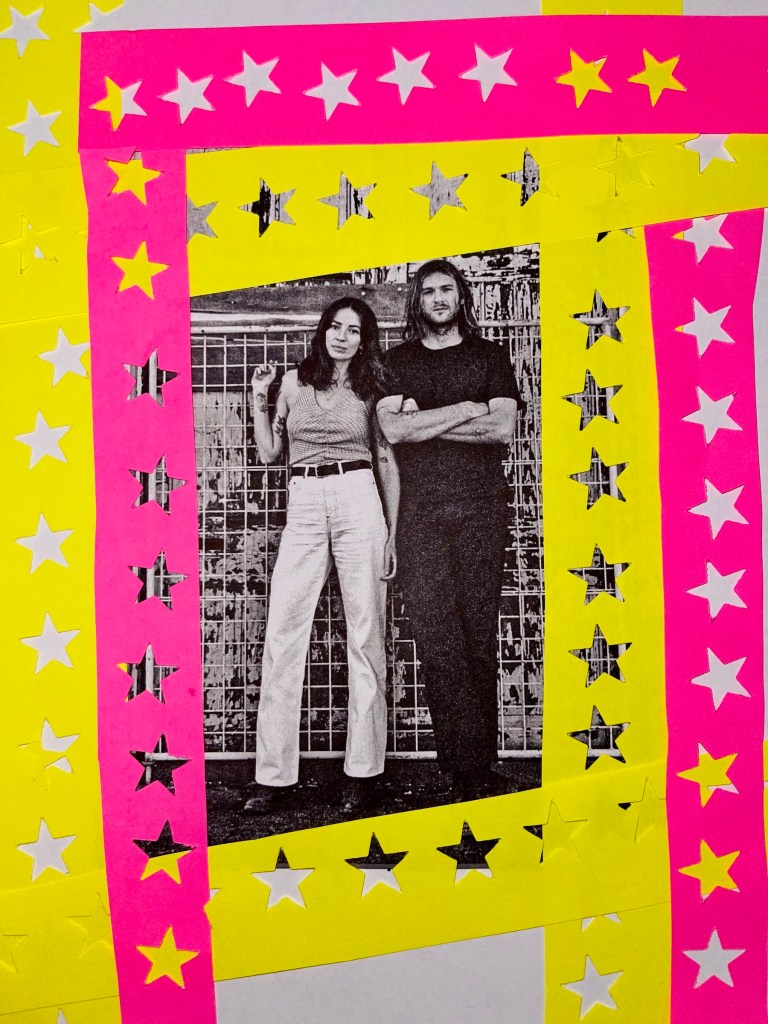

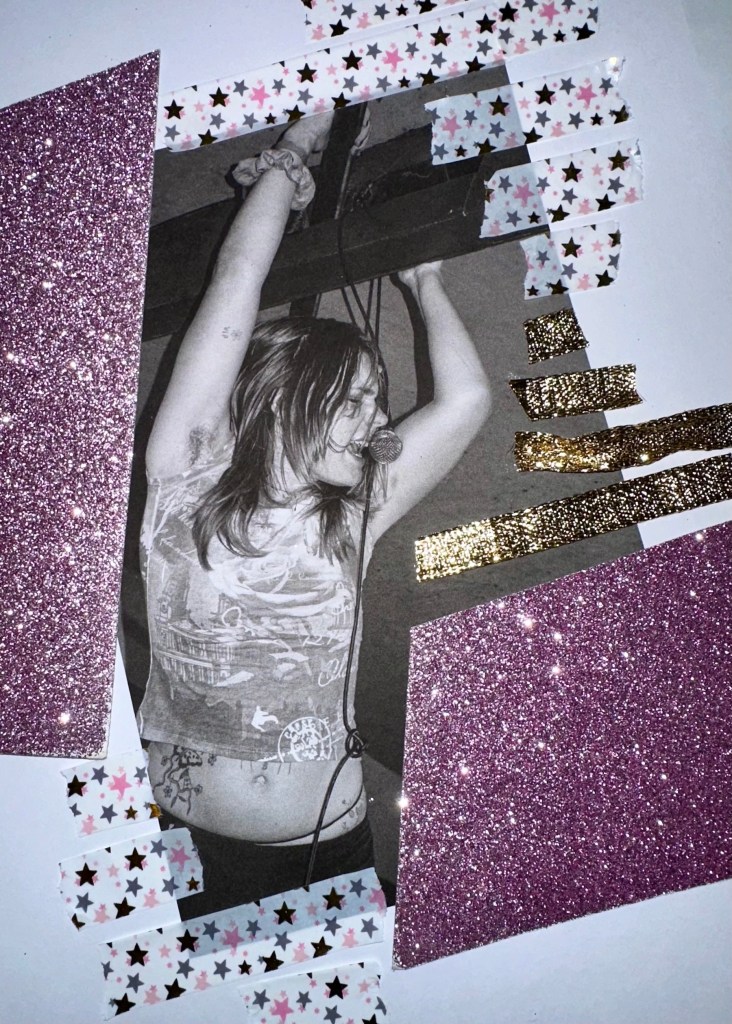

Optic Nerve from Gadigal Country/Sydney aren’t just a band you listen to, they’re a band your feel. A band that defies the worn out tropes of hardcore punk, and expands its boundaries. Reimagining it, to gave us one of the standout albums of 2023, Angel Numbers. It flew under a lot of people’s radar; if you haven’t checked it out, we recommend you do. They’re a glow-up that uplifts the communities they speak to and care about. Vocalist Gigi is deeply sincere, and claims her power on the record, which is lyrically inspired by a French mystic, anti-trans violence, and exploring signs. We caught up with her, last year just as the album was being released, to talk about it. It was meant to be the cover feature interview for a print issue we had pretty much ready to put out last year – but life happened, and things were rough so we didn’t get it out. Finally, though, we get to share the chat with you.

GIGI: Our record [Angel Numbers] indexes a few moments of really intense transphobic violence. It felt pretty emotional to put out our new record, given the context of the last few weeks. Having it come out while there’s Nazis gathering in Melbourne and in Sydney. And Kimberly McRae [an author and trans sex worker], the man who killed her, didn’t get a murder charge. A bunch of friends have been feeling… [pauses]—it’s been a really bleak time for transsexuals. With everything happening, I sort of forget about the record. I didn’t even realise the single was coming out the other day. It was weird to return to some of the ideas or hopes that the record had in what is a really heavy few weeks.

I’m so sorry that it’s been such a challenging time. The craziness of the world seems to feel overwhelming a lot of the time. It’s been great to see the songs from the record live recently. We saw three Optic Nerve shows in three different states.

GIGI: It always feels like such a privilege to go to a city that you don’t really know and have people care about the music. The Optic shows often have a different energy. At punk shows, it’s mostly bro-y dudes. Often, when we play, those dudes move to the back, and all these younger, more interesting people move to the front. There’s space for that, which is really nice. I actually got really emotional playing Jerk Fest. At the front there was all of these really wonderful young, queer and trans people who were shouting out for songs that hadn’t come out yet.

I know that the Decline of the Western Civilization documentary had a really big impact on you.

GIGI: Definitely. When I was really young, I wanted to be like a lot of the bands, particularly The Bags. I drew a lot of inspiration from her [Alice Bag]. Being so defiantly, an outsider. Also, that music seems way more interesting to me than a lot of super self-serious punk music. I emailed Alice a few times after the first Concrete Lawn demo came out and had this really sweet correspondence. I sent her the band’s demo.

I feel like in a lot of the Optic songs, I always try and channel the Big Boys. They were a Texas hardcore band. They were all skateboarders and drag queens, and really flamboyant leather BDSM guys writing these cheesy love songs and having fun. That feels way more interesting to me than flexing.

Was there anything specific that you wanted to do from the outset with Optic Nerve?

GIGI: I’d always wanted to sing in a hardcore band. The first demo and all of the earlier songs are a lot more straightforward hardcore music. Moving forward, the record is quite a bit more spacey. I would say, not really hardcore at all. The intention is to continue on that trajectory of getting a little bit more studio with it.

Joel, Joe, and John, who was the original guitarist in Optic, they had all moved from Canberra at relatively the same time and all started writing songs together. Then, they just asked if I would sing. So, I came into it with a bunch of the songs already written and did lyrics over the top. It was nice to ease in because at that time, I was playing in three or four other really active bands. To have almost a ‘burner project’ where I could turn up to practice and, I don’t know, be on Twitter on my phone [laughs], and write lyrics. Then, we started to play shows. It’s become a really fab, more creative venture for us all together!

Across the album there’s flute; that’s you, right?

GIGI: Yeah. I played flute as a kid. We were thinking about the flute as this sort of returning-to-childhood thing, which felt really nice. But we were also thinking about the record in parts, in the way you would frame a ballet or a really grand performance. We were thinking about setting up the listener—audience kind of engagement that our shows aim for. We were hoping to use the flute almost as this classical framing device that would bring people in and out of different moments on the record. Loosely there’s flute the beginning, middle and end. It almost provides an emotional structure to the music through flourishes. It was fun. I borrowed my boss’s flute and just winged it. I did it all in one or two takes.

That’s awesome. I love that! The album is playful, like your live show. It’s a cool lighter juxtapose to the heavy themes on the album.

GIGI: That’s it. When we were recording, we set this rule for ourselves that we couldn’t use any synths. We didn’t want to use any digital effects. So a lot of the record was recording a base of the song and then overdubbing things with really fucked up effects on it and then using heaps of tape delays and dubby effects to kind of give things this sort of synth-y ambient flutters throughout.

It’s nice to be playful. With the live shows, I play around and see if I can climb something on stage—like, climb on a speaker. Also, live, it’s worth protecting your energy. If you’re in a crowd full of people who don’t resonate with the kind of violence that the record talks to, it’s only going to be exhausting and exposing to talk about it really explicitly. Leaning into the playfulness of it and trusting that the people who will get it, will get it, was important. I’m glad that you picked up on the playfulness because I think it is.

That’s one reason that I really love your band! It’s hardcore punk but without all the gross stuff—tough guy nonsense, perpetuating traditional gender norms, racism, homophobia etc.

GIGI: Yeah, we’re something else.

Thank you for existing! I love people doing their own thing, standing up for what they believe in.

GIGI: For women and people of colour, anger is a really powerful tool. For boys, I don’t really know if it changes the world very much. There’s a lot of anger and a lot of hatred in the music, but I’m wary that the audiences who engage with it, that’s not necessarily a productive emotion for them to hold on to. Trying to make the shows feel a bit different to that is really important,

From your release Fast Car Waving Goodbye to the new record Angel Numbers, what do you think has been the biggest growth for you?

GIGI: The EP, we were just playing live. It was an assortment of songs; they are all really different from one another, in a nice way, but there’s not much cohesion. This record we wrote it to be a record, it was thought of as being singular, rather than writing music to play shows.

I’m proud of myself because now the music talks more directly to what I want it to be talking about and not just being vague, almost as a protection strategy. That’s how I feel listening to the older Optic stuff.

The newer recording we spent a little more time on. We still mostly recorded it ourselves. It’s a more mature of a record.

It’s one of our favourite albums of 2023! The booklet/zine that comes with it is really interesting and cool. I love that we get more insight into inspiration and thought for the songs. The title Angel Numbers speaks to seeing signs. What influenced that? Did you see signs when writing the album?

GIGI: The title is half a joke and half not [laughs]. I was interested in these practices of divination or magic or whatever that really rely on a kind of politics of faith and really believing in yourself. At the same time, it also thinks that those things are a little bit bullshit. It tries to peddle the fact that no one will ever make the world that you need other than yourself and your community.

I was feeling that at the time the record was made. Maybe I felt a little abandoned, and like people were pinning too much stuff on almost leaving stuff to the stars. It felt like things that were needed in the world were too immediate to pin stuff on hope or fate or the stars. It was like, ‘Oh my god, get your head out of your arse’. But finding structures that can make the world meaningful or powerful to move through, felt really important as well.

A lot of the record is about context and bending the context of the world and social communities that you’re in, or social practices or things to make yourself and other people safe. One of the ways that can happen is creating a structure for yourself that creates meaning in your life. That’s very much what these magical, mystical practices I was looking into kind of do at their core when they’re really successful. They give you a set of structures that can really meaningfully harness your power and bring it to the fore. That’s what the record is talking to in the title.

I picked up on the mysticism—that’s my jam.

GIGI: I was researching Silvia Federici (whom I left out of the citations on the lyric booklet for the album because she’s a massive TERF), this Italian Marxist feminist. She has this really fab book called Caliban and the Witch that talks about the beginning of capitalism coinciding with the mandate for gendered labour, necessarily creating a kind of subjugation of women. That coincided with women who were seen as independent, holders of deep spiritual knowledge, or community leaders being branded as witches.

She writes this really amazing historical overview of the beginnings of capitalism and the witch trials. Thinking about ‘witch’ as this kind of socially condemnable term rather than a cohesive set of magical practices. I found Marguerite Porete, the mystic and author, through that book. I got really obsessed with this idea of this woman totally on her own in the world, trying to make sense of God through her own desire or love or faith.

I got really captivated by this image of her getting burnt at the stake, and she’s just blissful and happy. Her almost giving over to the violence and persecution because it means not compromising yourself. That was a super meaningful image for me to understand. Like, you can never escape the violence or the risk or whatever of this world, particularly thinking about anti-trans violence. You just have to embrace risk and embrace joy in the face of that. It’s the most powerful thing you can do.

Has there been times in your life where you’ve experienced that kind of violence?

GIGI: Yeah. The record speaks to this few-month period where I got jumped four times and was put in the hospital twice. It’s exhausting, so brutal. One thing that I’ve been trying to get into people’s minds, which also feels hard to justify when the record is about a French mystic and angel numbers and all these things, is that there are no metaphors in it, at all. A lot of it is explicitly about the stakes—life or death in a very literal sense.

I am so sorry that happened to you. I can’t even convey words of how much this upsets me to hear.

GIGI: Yeah. It doesn’t feel valuable to list off traumas that anyone has gone through because it does just upset the people who get it, and then the people who don’t get it are just like, ‘Oh, that sucks.’ Instead, honing in on the ways that reverence and grief can exist together and hold each other up is really important to me.

The footnotes in the booklet are great.

GIGI: I thought they would be helpful for younger people to find out more about what I’m singing about. There was a period of time where I really lamented that a lot of the bands that I was getting into as a teenager had the same politics as me, but were really reserved about it. I was thinking that younger transsexual listeners could discover some of the things that are really foundational to my politics, that it would be nice to have a resource for people to go to if they needed to.

Our single ‘Trap Door’ is really powerful to me. It speaks to moments of violence and then moments of going out and having fun afterwards anyway. The other tracks speak a little bit more vaguely about liminal spaces or administrative violence or these kinds of facets that make up the record. ‘Trap Door’ is climatic, it talks about getting jumped. Making the music video was really healing. It was going back to something that has been really hurtful and really violent, and in a way making it beautiful and fun. If that makes sense?

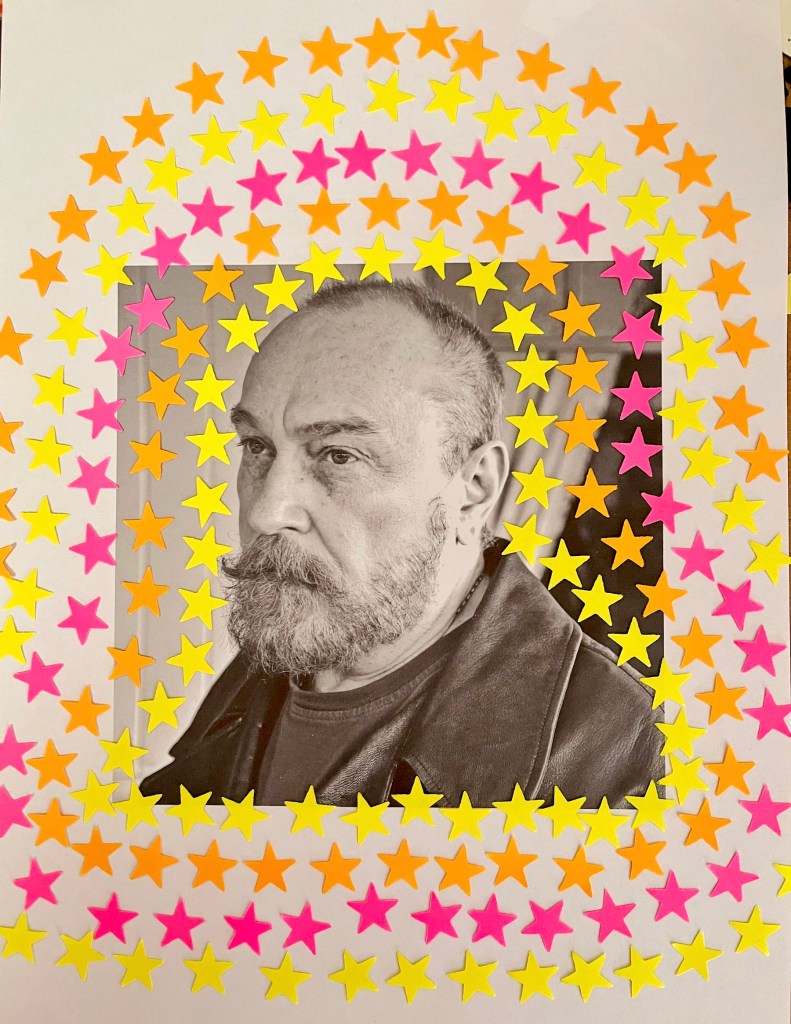

I totally get what you’re saying. I spoke with filmmaker and musician Don Letts a while back. He told me about, how punk was seen as this negative, nihilistic thing, but really, it’s about empowerment and turning negatives into positives. Like what you’re talking about.

GIGI: Yeah. Punk is about empowerment and turning pain into something more joyful that you can share with others. It’s about a commitment to never having to compromise. It’s also very much about community and making a space to feel and process emotion. While songs or bands may not meaningfully change the world that much, they galvanise people to come together, creating a sense of collectivity that is powerful and special. It’s about processing, feeling, and working out what I feel about the world. Allowing that process of feeling emotion to become a chance for connection.

Where are the places you find community now?

GIGI: When I was first getting into punk and hardcore, it would have been at Black Wire Records. Tom [Scott] and Sarah [Baker], who ran that, are like my parents. I used to go there every day after school when I was a teen. It was this DIY record store that put on all-ages shows in Sydney. I saw so many of my favourite bands there, and it really gave me my sense of politics as well as my music taste. After that, Tom and Sarah were running another place called 96 Tears that I was helping out at, doing the bookings.

Sydney is a really interesting city because it doesn’t have much creative infrastructure, so there’s not really many clubs or venues that are safe. I feel really grateful for the continuous structure that practising with Optic has. I know personally, for me, a lot of raves in Sydney or the warehouse parties have really been super informative to that sense of community as well.

But it’s always fleeting. The movements or people that this record is written towards, are never going to be the kind that have consistent, stable access to resources, like a venue or a building, or a place to come together. For me, community is always moving and that’s what makes it really exciting. That’s the real answer and also a poetry answer [laughs].

Poetry rules. In the booklet that comes with the record, it’s interesting to see the form of each of song on the page.

GIGI: Yeah, it was my intention to have them read more like poems than lyrics.

When I read them on stage from my phone, because I’m actually so forgetful, I have line breaks every time I’m supposed to breathe. People think it’s a nerves thing or anxiety. I don’t really get particularly nervous when we play. If I was to write the lyrics out how they’re originally written, it would be annoyingly long to write. Some are one word per line. So it was nice to come back and rewrite them as poems. Poetry is a little more contemplative and lets people in more than just like a didactic lyric sheet. I was hoping that people could read it and come to terms with it however they wanted to.

When I wrote the lyrics for Angel Numbers it was pretty much while we were practising in a little studio in Marrickville. I would just sit there antisocially on my phone and write ideas down. With the last song ‘Leash’ on the record, I finished those lyrics two-minutes before we recorded [laughs]; I was really putting off finishing the lyrics. It was nice because the emotion of the record could be really confined to this space with my friends, where it felt safe.

After recording, mastering, and the art was done, we sat on the record for 18 months. It felt like it came out at the right time though, it felt really serendipitous, given the political tensions of the last few weeks.

What else are you up to?

GIGI: I’m playing solo a fuck tonne in the next few month. Optic are really hoping to go back to Europe. Joe needs knee surgery so we won’t be able to play for a bit because he’ll be healing. Hopefully we’ll be able to write and record more songs. I want to sing more and shout less. But I don’t really know how to do that—I’ll work it out.

With your solo stuff, what can you do that you don’t do with Optic?

GIGI: I can make it in bed [laughs]. It’s the same emotions, but a different mode of address. They dovetail each other. Very inward and very much about my emotions: What does it mean to be angry? Or sad? Happy or horny? What does it mean to feel alive?

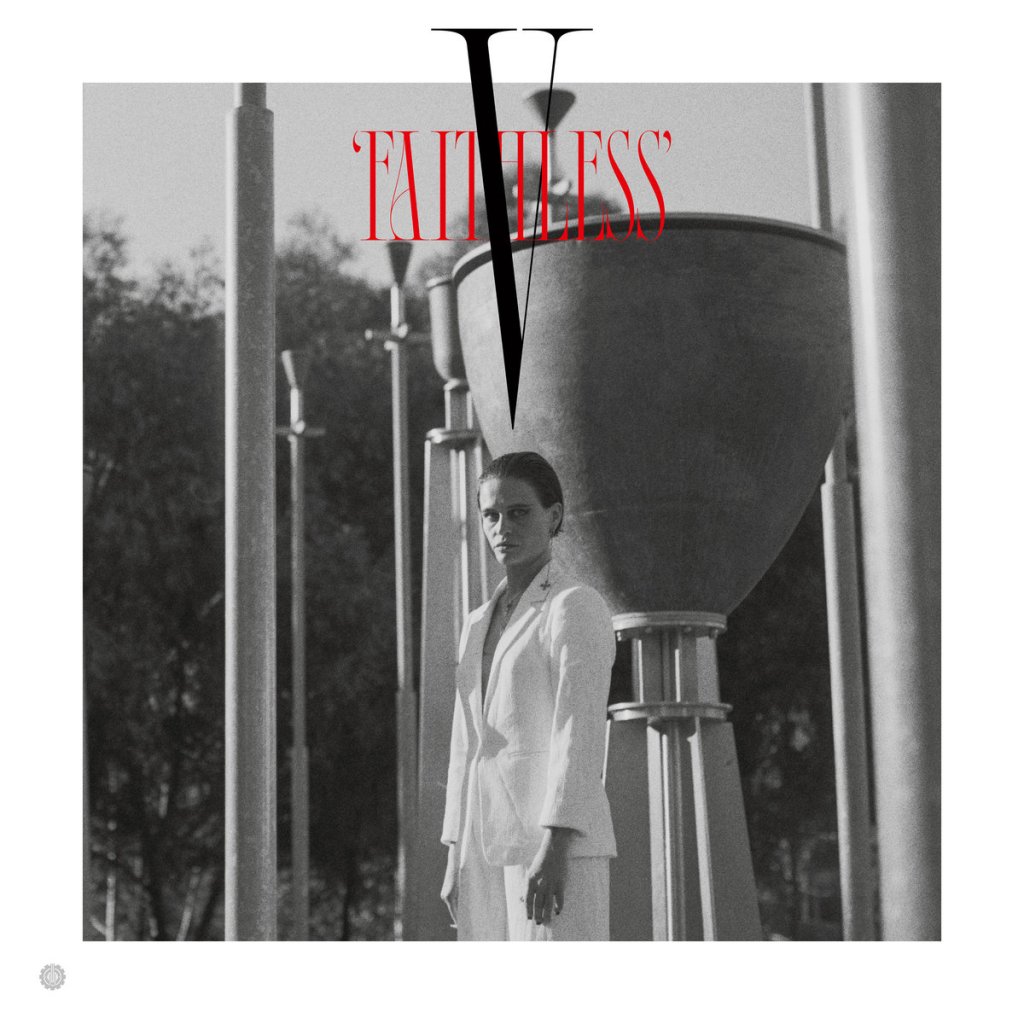

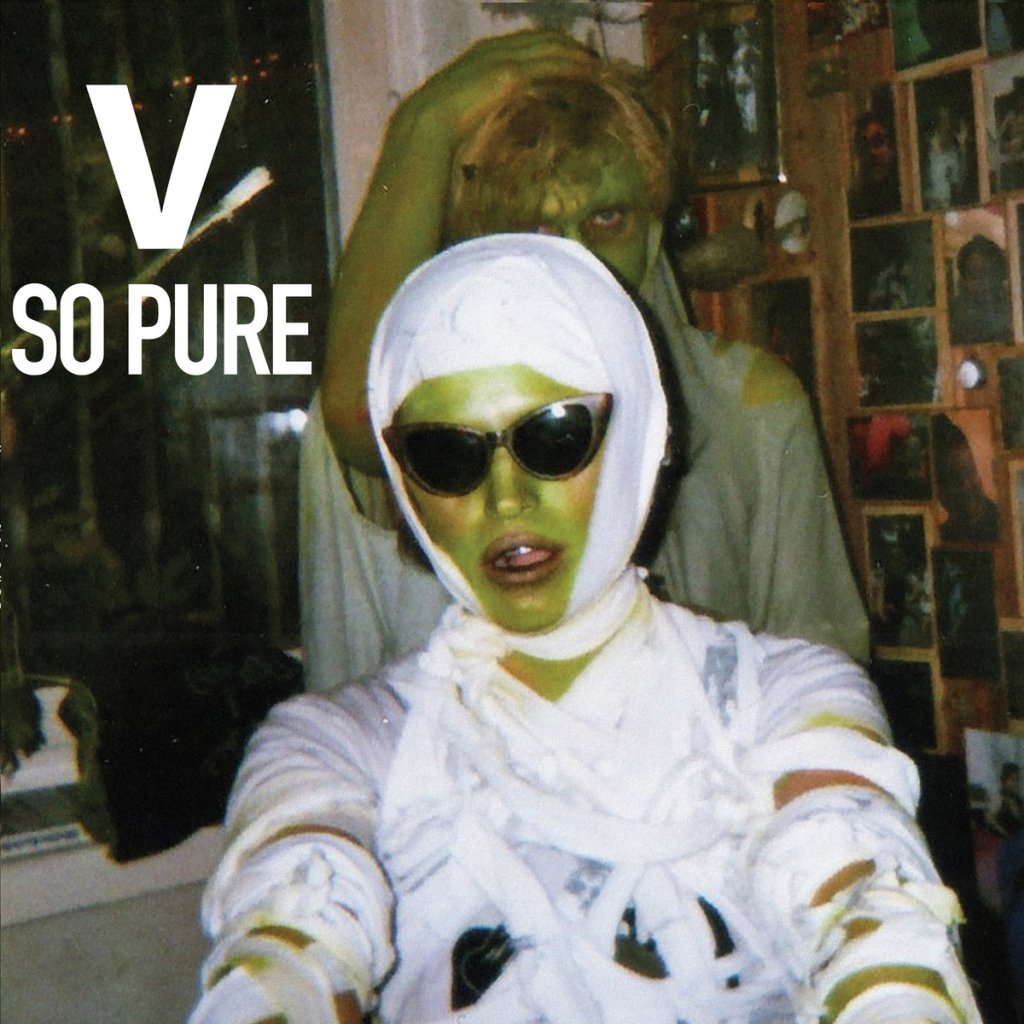

Angel Numbers available via Urge Records HERE. Gigi’s insta. GI music.

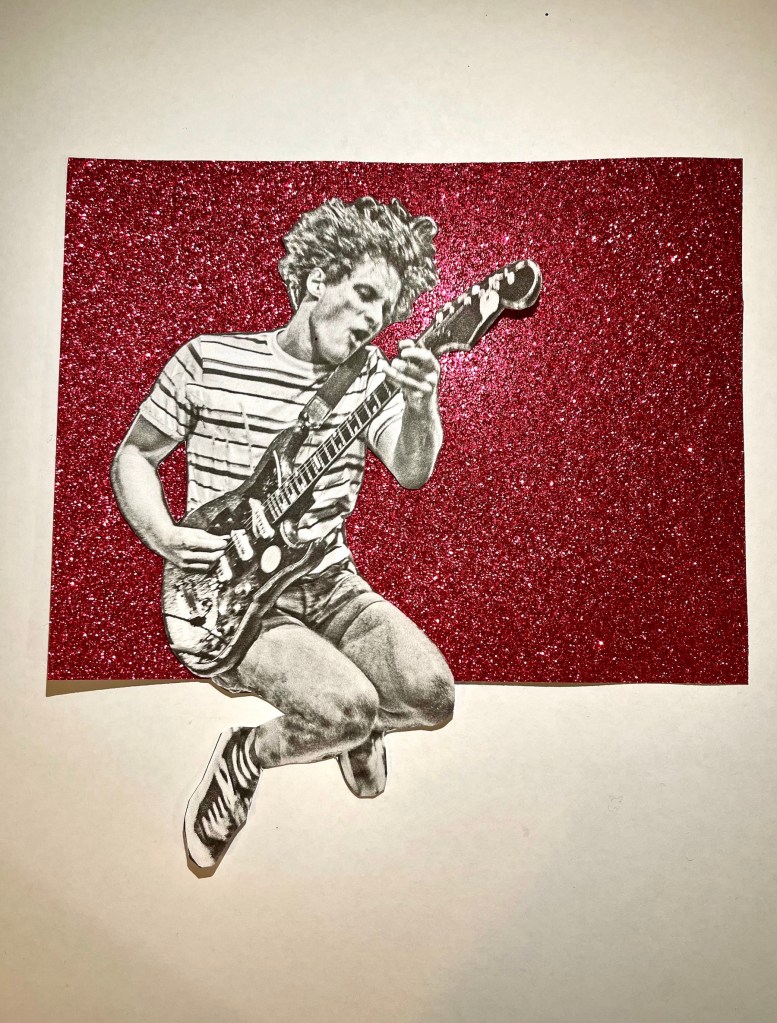

More Optic Nerve live videos – via the Gimmie YouTube.