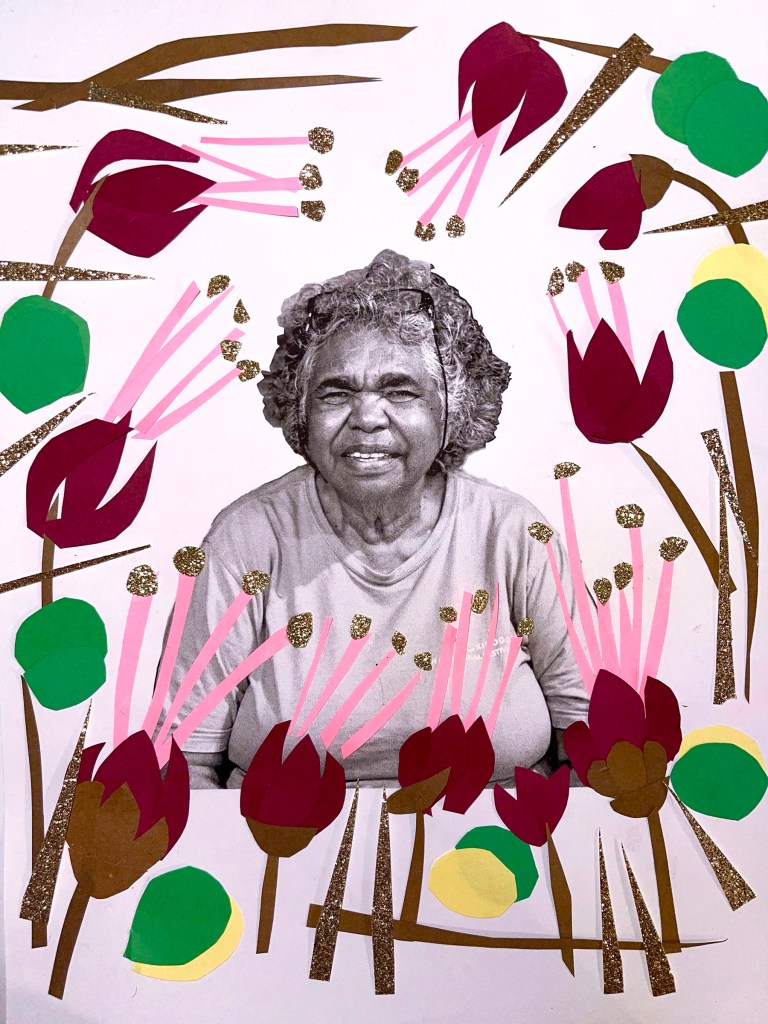

Kankawa Nagarra has inspired generations through her music, writing, and activism. To sit down with her for a yarn is a profound experience—one filled with laughter, truth-telling, and the generous sharing of wisdom. A Walmatjarri Elder from the Wangkatjungka community in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, she is a beacon of positivity. Known affectionately as the “Queen of the Bandaral Ngadu Delta,” Kankawa has dedicated her life to bridging worlds—whether as a translator, community leader, tour guide, or tireless advocate for Indigenous rights, community health, and environmental preservation. Her music, a blend of gospel, blues, and country, carries the spirit of her people and her Country.

As she recounts in her memoir, The Bauhinia Tree, Kankawa’s journey has been far from conventional. She survived a threat to her life at birth due to her mixed heritage, lived a traditional nomadic life in the Kimberley sandhills until the age of eight, and endured the injustices of the Stolen Generations. Taken from her family and sent to a mission, she was introduced to hymns and gospel music through the mission choir, later enduring the harsh realities of cattle station servitude. Kankawa rebelled against tradition—at the time, touching a wooden instrument was considered Men’s Business—to play the guitar, and in her 40s, she discovered the transformative power of the blues.

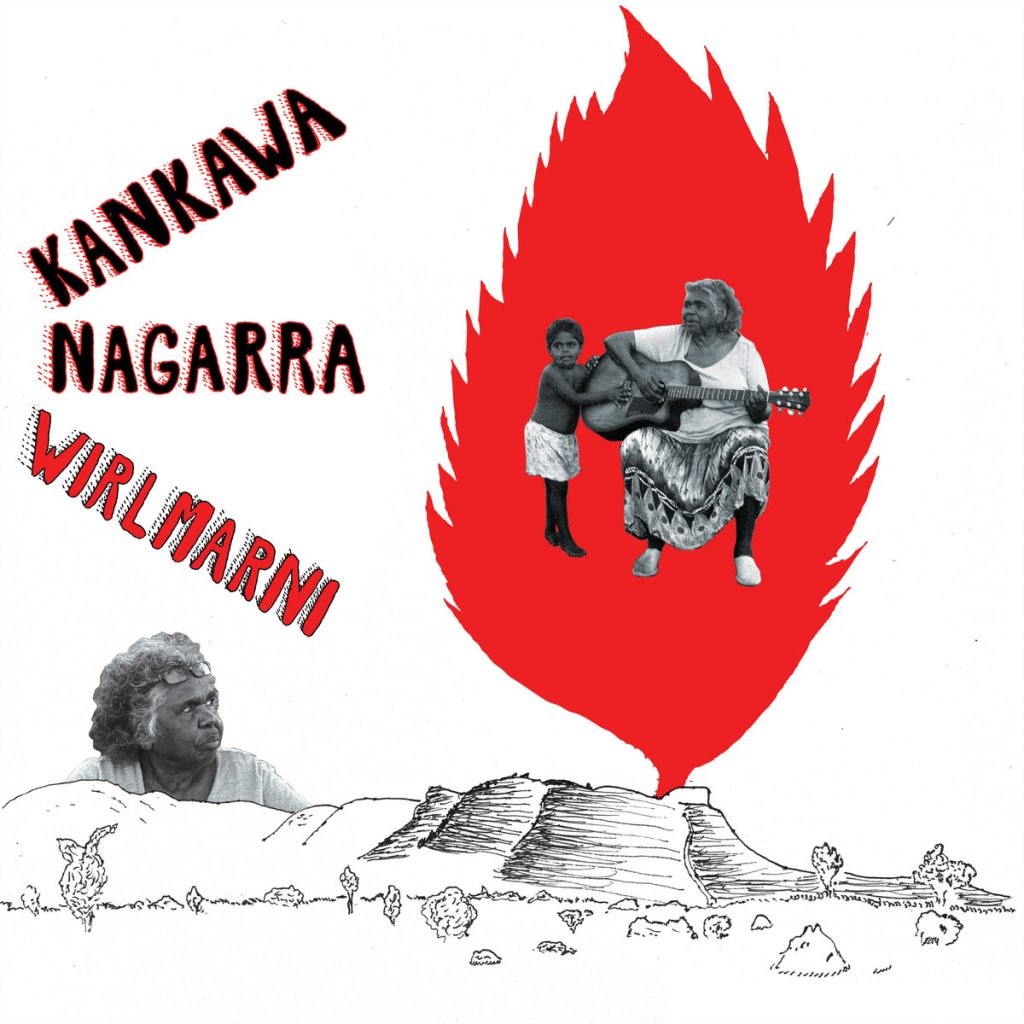

Kankawa’s contributions extend beyond music: she played a pivotal role in developing the Walmatjarri dictionary to preserve her language and toured globally alongside actor Hugh Jackman in a Broadway show. Her storytelling and songs celebrate thousands of years of culture while addressing modern challenges, from community health to substance abuse awareness. In 2024, she was awarded the prestigious Australian Music Prize (AMP) for her debut album, Wirlmarni, a record that beautifully captures the sounds of her Country and daily community life.

Gimmie spent time yarning with Kankawa in the car driving through Meanjin peak-hour traffic to get her to her show with Darren Hanlon on time, also while driving her back to their apartment, and sitting around the dinner-table after the show. She was very generous and kind sharing her story, knowledge, and laughs with us.

Previously, you’ve mentioned lyrical spirituality in relation to how you write your songs.

KANKAWA NAGARRA: Yes, that’s right. That’s the name I gave it. We Indigenous peoples have this thing called the lyrical spirituality, because most of it—you look at the Dreamtime and the Dreamtime stories, you know—there’s a lot about lyrics and forming lyrics and singing. Singing life or death to yourself. Because the Dreamtime story tells—in my Country—how Dreamtime people made up lyrics, in their minds. Suddenly, they either sing themselves to death or sing themselves to life. That is what I thought I described. That’s what we are. We are song people. Because—like I say to a lot of people—we are spiritual people.

I run this project—well, I’m starting to—I want to present it in retreats, where a lot of people—Westerners—come and learn about the spirituality of us. We Indigenous people have two components. We have this one to listen to [motions to ears/mind], and then there’s another ear here [motions to stomach/heart]. My project is called Ears of the Heart.

Most people only got this listening here [motions to ears again]. But they don’t convey the story down here [motions to stomach again].

To listen with our heart, not our head, if we are to truly know Country. To have open minds, open hearts and an open will wherever we are.

KN: Yes! A lot of people ask me about the last referendum, how that happened. Had they listened more here [touches stomach] and conveyed the story it could have been different…Because of those fears—these people will steal your backyards—people had fear. But had they listened to the story more closely, they’d learn that the land owns us, we don’t own the land—we are only custodians of the land. How can we steal something that there’s no ownership of. We look after it. That’s right, we’re custodians only. There’s no fear. We would’ve had a different outcome had they listened more, you know?

Totally. Being mob too, I got asked about it a lot by non-Indigenous people. The simplest way I could break it down for them was that we need to keep the conversation going. To do that, we need to vote yes. If we don’t and vote no, that will stop the conversation and make things harder for relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in this country. We need the conversation to keep going and we need to work together, not against each other.

KN: Yes, that’s right. The conversation has to keep going so that people in this country can learn.

At the moment I work for my daughter, she runs a tour guide business in Fitzroy Crossing. They hop on that bus of 20 people and they’re from all over the world and from all this country.That is what I say to them. I bring cross-cultural awareness and this listening and hearing the story. They nearly always talk about the failed referendum. I say to them, Australia listened only with these components, these ears here in the head, but they didn’t convey the story down here in the heart.

When you’re writing music it comes from there?

KN: That’s right. That’s someone here from the spirit, from here [motions to stomach]. I have to listen to the stories. I’m thinking of writing a few more since I joined, this little record label [Flippin Yeah/Mississippi Records] with Darren [Hanlon]. There will be lots more, I want to write more songs and create another album.

You sing in in Walmatjarri, other traditional languages of your family, Kimberley Creole and English.

KW: It doesn’t matter anymore, which way I switch, English or my language. When I was younger, you grew up with your traditional songs and dances, like when people put out ceremony and all that.

What is one of your first musical memories?

KN: Western music came when I was working, because I heard Slim Dusty and all of those country greats. That’s when I began to be quite interested in the Western music, and was all about the instruments that they played then, you know, like the guitar. But then there’s the music, the old music, the corroboree, dances and all that, songs—that’s what you’ve grown up with, with all of the instruments they play and how people play it in the east part of us, the territory and all those other places. But my desert people we were only used to tapping the boomerang and the null nulla for instruments.

I know that you really liked Buddy Holly!

KN: Buddy Holly, yes, oh dear me [laughs]. After I started listening to country and western, then rock and roll came on the scene in the ’50s and ’60s, and then I started doing a bit of rock and roll. I even mimicked some of the songs of Buddy Holly.

But you didn’t really like Elvis, right?

KN: [Laughs] No, not much, yeah. Only Cliff Richard and Buddy Holly, and then I discovered the blues afterwards. I thought, this is more like me. The blues, it’s very repetitive. Many songs are very soulful and heartfelt. More story, more of what Black people suffered over there [USA]. You related to it more.

I understand that when you first wanted to start playing guitar you weren’t allowed to because it is made out of wood and that was Men’s Business, and it was forbidden for a woman to go near something like that.

KN: Yeah, that’s right, a cultural thing. Yes.

I’m glad you broke the rules and started playing guitar.

KN: It’s just something I wanted to do so much. I love it very much. I’m going to make music, I don’t care who tells me anything [laughs].

Your first guitar was made from a tea box?

KN: Yeah. There was a friend of mine, he was my uncle. He was a blind man. We were working on this sheep station. We get together and he’d tell me that we’re gonna build this guitar. He told em to go and get us a tea box, nails, and copper wires. It’s quite funny [laughs]. And he made the tune himself with his mouth like ‘da da duh da da’ [laughs]. But later on when he really got a hold of a guitar, he didn’t learn to play.

One of my songs is a very sad song for my uncle who removed from my family from the desert there. They were the last remaining people who roamed the desert in Western Australia. But the government took them, placed them in communities. Most of them have passed away, and there’s only one or two people left. I sing this song ‘Pain O Pain’ it’s such a sad story. That’s the one I had a struggle with it when I first wrote it. I was still doing tour of the desert at the time with another music group called Desert Feet. We went to this place where all those old people were taken from the desert and put there. And I started writing this whole idea of music. I had a hard time trying to, and thought, should I ever sing this song? I kept crying a little, being emotional. There’s another song that I was telling them, the band, I have written it, but I’m having a hard time trying to sing it now. It’s a story of the suicide of my grandson.

I am so sorry for your loss, Kankawa. That’s no good. That would be hard for everyone.

KN: Very hard. The mother is still suffering. He was beautiful, he was a musician, he played bass for his brother’s reggae band.

That’s so wonderful he played music too. What songs, that you play, bring you a joy?

KN: I’ll do one tonight it’s not a very good story though, it’s about land being taken away by the mining company in Western Australia. The iron ore. It is ‘Train Train’. I try to get people to do a conga line, so at least they can sing with it and do some dancing and that gives joy. I’m glad the little children do it. It’s so great just to see so many generations of people there. Very nice.

Another dance and happy song, talks about the land where my place is, there’s plenty of food there, like turkey, goanna, emu, and vegetable food.

What are you most looking forward to doing when you get home from tour?

KN: I just go back to the community and while away the time. Time ends. No more time, no [laughs]. The sun rise and sun set, that’s it. Put your watch away. I’ve got 11 greats (the grandchildren), but some of them are going on holidays.

Do you have a favourite spot where you just like to go hangout and relax?

KN: My place there’s a flat outside where we all congregate, sit down and tell stories. So that’s a nice place for us. And sometimes we go hunting sometimes. You can sit down whenever you are.

Holiday season is the time for ceremony. There’s lots of beautiful ceremonies for boys.

Do have a favourite blues musician?

KN: Yeah, there’s a few of them. There’s one that influenced my style, Big Bill Broonzy. Jessie Mae Hemphill, that’s a style I use in ‘Train Train.’ I’d love to play Mississippi John Hurt, my way, but I can’t, you know. I’ve got a fright playing the guitar; it’s difficult to think of picking stuff.

I don’t see myself as an entertainer but I see myself just sharing, about me and about our people.

We love how you do a Q & A session before your sets? It’s nice that you get to share in that way.

KN: One place we performed, Darren gets message from this person complaining about him singing his new song, saying it’s all to do with fascism, Trump-style and all that sort of thing. The person said he was feeling uncomfortable about it. So he gets this horrible message from him because of the redneck towns that we’ve been through, they weren’t too happy. He was singing something that really touched the nerve. It’s because of all that hype that’s going on in America with Trump and. It looks like this country is going that way too, do you think?

Unfortunately, yes.

KN: Like, what’s going to happen to our flag? What’s going to happen to the Indigenous flag? You’ve got, what’s his name…

Peter Dutton?

KN: Yeah, Dutton. It’s terrible. Because he said straight up, he won’t be standing in front of the Aboriginal flag.

I know, it is terrible. He is trying to further divide people despite his guise of uniting. With all of the terrible things going on in the world, is there anything that helps you stay positive and hopeful?

KN: I do my best. I’m a Christian person because I believe in God. That’s the compassion that Jesus Christ himself taught. It exceeds beyond all the horrible things to me, because this is a way of now finding God through the Spirit. Because we are Spirit people. In the past, when I was removed, it was all to do with religion. Religion has been really pumped into us. But our people need to learn that we are Spirit people. We are comfortable. We can approach our God that way, through our Spirit. And that’s why I’m comfortable. It doesn’t matter who I speak to tonight, whether there are redneck people there or not. As long as I share myself and be happy.

Do you think people sharing their selves helps the world?

KN: Of course, it does. That’s what I see in myself and how that giving feeling is of yourself. The world is a mixed-up place. You never know whom you touch or whom you influence in any way. Who am I to keep myself to myself and say, I’m not going to be out there, I’m for myself, not for them over there—it’s not me, I can’t do that. I’m here for the world. The world needs me. If I have to give to the world, let me do it, as much as I can in an honest way.

That’s how I feel too! Is there anyone like in your life that really touched you?

KN: Yes, many have touched me. I feel a lot of people have been part of this journey with me. I’ve learned a lot. I am in a place where I’m still learning, even in my old age [laughs].

For instance, I carried a lot of prejudice because of my past, because of all the discriminatory laws and all this sort of thing that were happening. I carried that burden a lot. I thought, well, I’m not going to change. kartiya is kartiya with their white faces. I thought, well, I’m going to judge them that way. I’m not going to judge them by the spirit, whether they’re different in their spirit. So I did that a few times.

But then I met an Irish musician, who was white and red-faced, with red hair and a red moustache and all that. I was sitting opposite him at this little thing we were invited to—drinks, I don’t drink anyway. They were all Irish people in Perth, and he sat opposite me. I just judged him by the looks. Freckle face, white face, red hair, and red moustache. And I thought, this guy hates me. He hates the Black people [laughs]. I was very discriminatory.

He sat there, and my niece was there with me. He didn’t talk all night. He just played music with another nephew of mine. And I thought, my word, this guy is so prejudiced, against Black people.

Anyway, the very next day, I get a friend’s request on Facebook. I ask my niece, ‘Now, who is this guy? Who is Ciaran O’Sullivan? He’s sending me a friend’s request.’ And then my niece says to me, ‘That is the guy that was sitting opposite you!’ [laughs].

I added him to my friends list. And since then, we became really, really good friends. We bonded, and we shared music together. Now it’s a different thing, as even our spirits are bonded.

I thought, well, I’ll never judge people by the looks again. That’s a good lesson for everyone. I saw a lot of things that really, really touched my spirit with him.

There were times when he and I went out to a party after our music, after doing my show. He said he felt so isolated because he doesn’t like Irish jokes or people who say stuff like that. There were people in there, real kartiyas, Australians, and he felt out of place when they made these Irish jokes. The Irish were very discriminated against. He nearly cried.

Another time, someone was—one of the kartiya, an old lady—grilled me about my life. I was beginning to tell her about it, and he was just sitting there at the table next to me. And noticed how this woman, was like as if she didn’t have a feeling, was there asking me about my life. I told her that I felt suicidal a lot because of all the pain that I went through. He was sitting next to me, this Irish friend of mine, and I could see his face got red. Then he started crying. He just stormed out from the table and went into the bathroom and cried because, how dare someone do that sort of thing to me, his friend?

I had to console him. I said, ‘I know, look, come here, let me just hold you, because I’m used to these things. I mean, it’s not a problem to me now. I’m over it. I’d like you to feel that way too.’

Where you born in Brisbane?

Yes, I was.

KN: Lovely. I’d like to meet all the people here. At the shows, I wanted people to welcome me to the Country. Because being a different tribal person I like to be welcomed to other places. I want to help people to welcome us to another place, where you traditionally don’t belong there. Because I hope people will welcome our people from another place. They do smoking ceremony. My daughter does smoking ceremony, it’s lovely. She does cross-cultural awareness too.

I am a truth-teller. That’s all I can do for society.

Is there a lot of musicians from your community?

KN: All of my nephews are, they do country or rock. Then there’s heavy metal, but mainly reggae. One of my grandson’s was a reggae singer. But he’s in prison at the moment, so when he comes out I want to help him connect to Darren and the stuff that I’m doing with Mississippi Records and Darren’s label [Flippin Yeah].

Why is music is important to you?

KN: Music is healing. Music is important; it’s a spirit thing for us. Because it touches that part of you. Passing the healing to people is important. That’s how our people approach music.

The Dreamtime people were lyrical people; we are lyrical people. We sing life or sing death. If you’re going to be strong in your spirit, say, ‘Well, now I’m giving music for spiritual health.’ Be strong so that people can go on and live in this world. Be a contributor to the world rather than be someone who takes from the world.

That’s what it is, I think.

Yes! I love that. I love too, that throughout your Wirlmarni album, there’s lots of nature sounds.

KN: Yes, that’s right. It’s mainly all the wind and the birds, especially the wind when it’s blowing through the trees, you can feel the land. You can even feel the groaning of our Ancestors, when it blows through the trees. I live in that Country. We know all of the birds names

Do you have a favourite bird?

KN: Yeah, a butcherbird. Good sound. And then there’s another one called Jirntipirriny that’s a Willy Wagtail. When what happened to my grandson happened Jirntipirriny hung around my daughter lot. A couple of them visiting my daughter’s camp. We were thinking, what are all these birds doing? Jirntipirriny is close to my daughter, so there must have been something that they felt that they needed to be near, after he went.

That’s lovely. I had a Jirntipirriny that would visit me when I lived at my parents’ house every time I was depressed.

KN: That’s good. When I hear it in the morning in my community, I think, oh, thank God you’re back, and I talk lot it. I’ve written a lot of things about it, reflections about the butcherbird.

We hear them in the morning in the park across the road from where we live. When I hear them I know it’s time to wake up, it’s when the sun starts coming up. If I wake up and I don’t hear them, I know it’s not time to get up yet.

KN: [Laughs]. Yeah, that’s right. You know, when you hear it, it’s time to get up.

Do you do anything that’s like meditation?

KN: I pray and, of course, read the Bible. I love Country. I just sit there and listen. That’s why I’m with this project, Ears of the Heart. I tell people to walk barefoot on the ground and feel the heartbeat of the earth. Listen.

This one exercise I did with all the kartiya, I tell them to go out there on Country and stay for at least more than an hour and listen to the sound of the crickets, the birds, and all that. Then I’m like, ‘Right, what you heard? What did you hear with those sounds?’

Doing that, you know, so more. They need to have this spirit connection with things that they hear or when they tread on the ground.

Yes, it’s important! Your album’s dedicated to your brother?

KN: Yeah, it’s dedicated to my brother, his name is Frankie. He had a bit of a problem. He had this mental problem, schizophrenia. But he’d visit this recording crew. There were four of them doing it, and they all lived in my house in the community while we did it.

He’d visit them every day. He said, ‘Give them a good feeling.’ And one of the men, he noticed, you know, it’s a fashion now where they wear jeans with torn knees. He came and said to this man, ‘Nah, he shouldn’t be wearing that. I’ll go and get new clothes for you.’

He went to his house and gave him the new pants and new shirt. [Laughs.] Ever since, he’s been wearing it now. He’s a bit of a hippie type of guy; he lives out in Melbourne. My brother felt a pity for him that he shouldn’t be wearing a torn jeans. Even though it was a fashion choice.

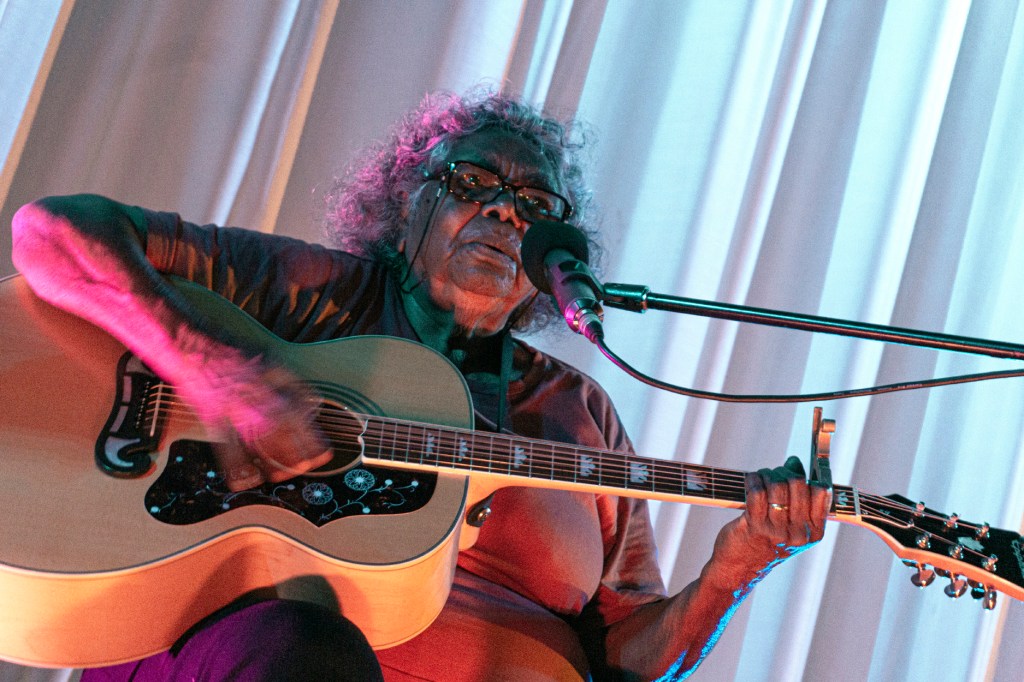

[Laughter]. How do you feel when you’re on stage?

KN: I feel strong. I feel good. I feel that I’m giving. II feel I’m giving to people. You could tell the audience felt happy from that. When I looked down at the back there was a dad holding a baby and they were dancing away. And that made me feel really good that I can give that vibe.

You’re literally moving them!

KN: Yeah!

You were giving to them and they were giving to you.

KN: Yes—that’s it. That’s how I see it. It’s a cycle. It makes me feel happy. The last song was very, very sad of course. It makes me feel about the Old People.

You were singing with your eyes closed.

KN: I wanted to cry. I’m so used to it now, though. I try to sing the song about the Old People who are gone. I want to write more. I’ve gotten inspired for more. More storytelling, so the kids can hold on to things. Stories are lessons for us to learn and take them on.That’s why it’s important to me to do Ears of the Heart.

When I do this program, last time we did one in Canberra camp, my part is to tell the Dreamtime stories at night in this painting that I did; a couple of paintings that are metaphors. But they look like they really, really don’t care for that, but I talk about that and tell them, look, this is a story about systems change. Thinking how they need to think. We say to them, this is all about finding you, finding yourself. Where are you? What has happened to you? Indigenous people are spirit people, our spirituality is consistent with this land and everything about us. So when you see how they’ve lost it, I say to them, Guess what? You’re an Indigenous person too. Because remember you came from a Celtic origination in that day, that’s an Indigenous part of you. I say to them, go back and find this spirit, find your Indigeneity way back there. Where did you lose it? I go through all that sort of thing in this project about listening, and hearing, hearing themselves and find yourself.

My kids used to ask for Dreamtime stories. Their father, he passed away in 1985. But they’re old men and women now. The two boys, two men, used to always bug their father and say, ‘Oh, tell us that Dreamtime story about the spear and that singing man.’

Like, seeing people, a doctor, where they fix people. But this man wasn’t fixing people. He had a good friend, a spear, but they were evil, both of them—they were cannibals. Every night, they’d travel from one tribe to another, all for the fact of eating those people.

That man would sing them to sleep. This is the way our camps were, with the fire in the middle. The singing man told this lot to go and sleep in a line, but they didn’t realise what he was doing. Then he’d run to the bushway, get the spear, and say, ‘Cousin, come out, they’re ready now.’ To eat.

And so, when I told that story to them, it was quite gruesome, actually. I’d say, ‘Well, you listen to the story tonight over this campfire. And overnight, write it in whatever form—poetry or any other form—and tell me the next day what you heard here in your spirit.’

The very next day, with the song of the cannibal spear, they said, ‘What is lulling me to sleep?’ That’s what they picked up from there. And being a climate change advocate, this is great, I thought, because what is lulling us to sleep when the earth is dying?

We need to be more aware.

KN: Yeah, more awake. Because the cleverman was putting them to sleep, so they can eat them, see. So our earth is, what are our people doing to us? Killing the environment.

Not paying attention to it at all sometimes?

KN: Yes, not paying attention, and it’s putting us to sleep. We’re being put to sleep by so-called cleverpeople—they sing us, these corporates and all that—what they’re doing to the earth.

It’s good when we start telling people that, educating people. And they’re listening, right? They start to take notes.

Yes! Is there any kind of song you’d like to write that you haven’t yet?

KN: Yeah, there’s a lot of songs. There’s one song I try to write; it’s called ‘Dancing to the Firelight of My Dreams’. It’s dancing around the campfire, but it’s my story of getting old. How the fire is like a metaphor of my youth. The flames went and rose higher and higher, and over the years, the embers died out [laughs]. What I’m telling you about is my youth going.

Does your youth going bother you?

KN: No, no, no, nothing. A lot of people seem to worry about it, you know? [laughs] They want to live forever. How much longer I’m mobile, I don’t know. God knows, that’s all.

He’s given me this gift for all of you. Come on, share it. You make the most of it.

There’s a lot of people who, in my Country—Fitzroy Crossing is a Black town—but a lot of them, they don’t feel brave enough to be out there and tell their story, maybe through music or coming out there, be brave and all that about everything.

So it seems that there’s all these restrictions, these inhibitions, that keep people sort of in prison or shame to be out there. Lack of confidence.

What gives you your confidence?

KN: I’ve grown a lot, with being overseas and then travelling—with Hugh Jackman and all those sorts of things. I’d be performing to over 80,000 people every night because they love the man himself. The confidence just builds up—it’s no end.

When we played in New York, Hugh asked me to name anyone famous—he had all these people in his phone—I’d like to meet, and he’d try to get them to the show. I said, ‘Ray Liotta.’ I like his films, but not from his gangster ones, though. He sent him a message, but he didn’t come.

At one show, I saw a fella coming down the stairs and went, ‘Spartacus!’ It was Kirk Douglas.

[All laugh]

That’s fun! So you’d encourage your people to get out there and give it a go? To be brave and just try it.

KN: That’s right, try. True. My daughter—when she started her tour guide business—she’s got five people working for her, she says to them, ‘There’s three buses coming today, there’s 20 people on board in each one of them. Go on those buses and take someone else with you who needs confidence, so they can watch you, how you do it.’

That gave me confidence no end, talking to these different kartiyas from all over the world. She lives with this one girl that’s drinking, and she doesn’t feel confident enough with herself. She says to her, ‘Guess what? You’re building confidence with all of us now, when we talk to these people.’

So this job you got is something—it’s helping us build more and more. It’s helping the younger ones too, when they feel so inhibited. We gotta help each other.

LISTEN/BUY Kankawa’s music via Flippin’ Yeah Record in AUS or Mississippi Records worldwide.