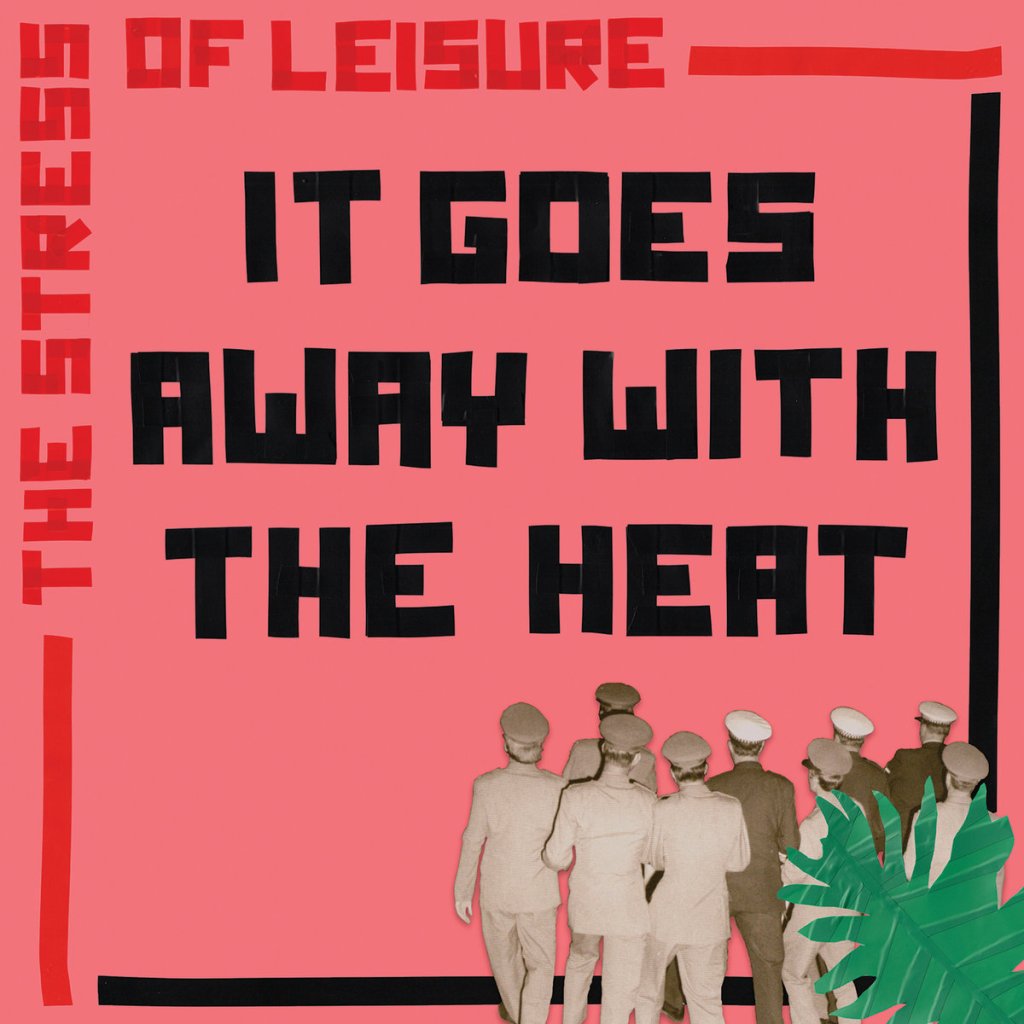

Following the success of their 2020 album Faux Wave, Meanjin/Brisbane’s own The Stress of Leisure return with their eighth studio album, It Goes Away With The Heat. This album sees the quartet dive back into their signature mix of post-punk, faux-wave, and a touch of weirdo.

It Goes Away With The Heat was recorded at Phaedra Studios in Melbourne by John Lee (known for his work with Mod Con, The Murlocs, The Stroppies, Laura Jean, Lost Animal, and Beaches). The band embraced a rawer, more live feel, channeling the energy of early Modern Lovers recordings with minimal takes and a spontaneous edge. The album’s themes resonate with today’s era of hyper-politics, and the world feeling like it’s moving both too rapidly and too slowly at once. The album is full of tension, with brooding heat and simmering between quiet and thunderous outbursts, much like a sub-tropics summer storm. The album also speaks of the impacts we can have on one another.

A few weeks ago, TSOL’s Ian Powne and Pascalle Burton dropped by Gimmie HQ to chat about their latest album—a reminder that in rock ‘n’ roll, having fun and being a songwriting wiz aren’t mutually exclusive. They’re sly subversives, crafting playful tracks packed with sharp social commentary that are guaranteed to light up the dance floor. It Goes Away With The Heat is one of the best albums to come out of Brisbane this year.

PASCALLE: We just launched the album It Goes Away With The Heat,which was really exciting. We recorded it July last year so it’s a relief to have it out now.

IAN: The new songs are fun to play and I’m feeling optimistic about it.

You said that the songs are really fun to play because you wrote them so they’re easier?

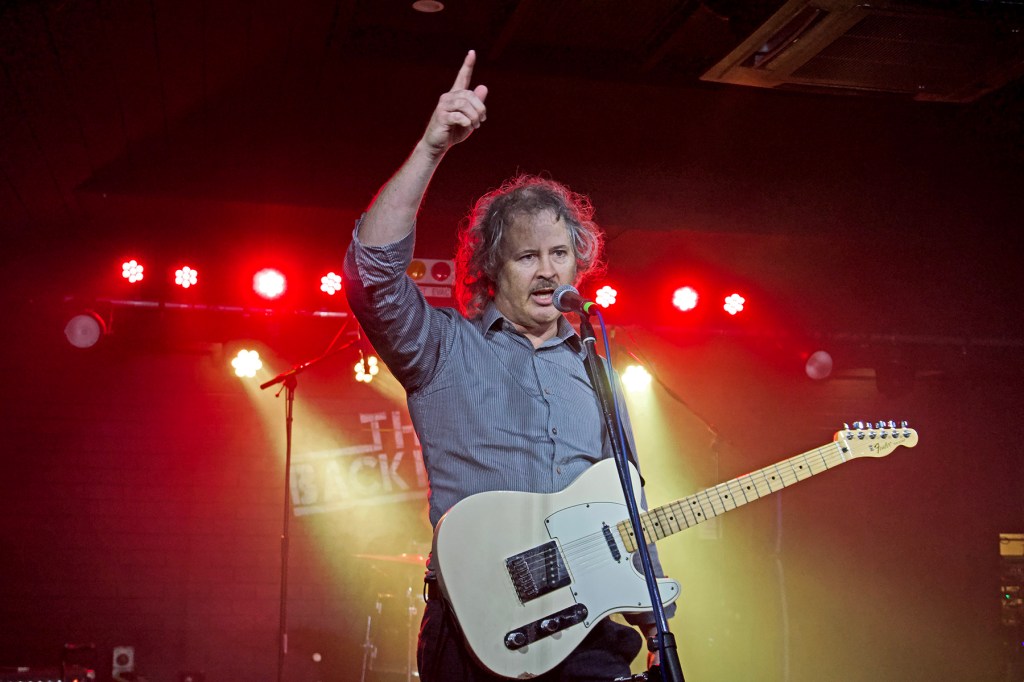

IAN: Yeah, because a lot of the guitar lines I’ve been doing more recently—probably the last five or six years—are guitar lines where you’re playing, and you have to think about the physicality of playing the guitar. Not all, but a lot of them, are guitar riffs or lead lines mixed in with rhythm. Whereas this is more straight-up rhythm, and so I’m more of a rhythm guitarist than a lead guitarist. Lou Reed said that as well. They’re fun to play in the sense that I can just sit in and enjoy the performance more. Usually I don’t know anything that’s going on, in terms of a vibe of a crowd or anything. I’m not nervous, I’m just consumed with the physicality of concentration. Generally I’m getting it 90% right. With these songs I can look around a bit more, which is fun.

When did each of you start playing the instrument you do?

IAN: The 1990s. I was intrigued by music. I had a curious mind when I’d hear songs, and I really loved music. I didn’t have a broad experience of cultures or genres; I just heard the music that I could access. I was always looking for something, that sense of defining ourselves through music—how we identify and what our identity is through it. I was on that road of exploration. My mum played the piano, and she was always urging me to play a musical instrument. I don’t think she had the patience to teach me the piano, but I think she must have planted a seed of musicality. So, it was a combination of curiosity, music, and a desire to identify and have fun. I always had a creative mind, so I was interested in where that curiosity would lead me, in terms of both a musical instrument and the influence of music—especially my mother’s.

What about you Pas?

PASCALLE: I started playing keys in The Stress of Leisure. I had always been singing, and that was a constant thing, whether it was just as a hobby or in a project. I remember Ian asked me to sing backing vocals on the album, and I had always really loved The Stress of Leisure’s music. This would have been album two, Hour to Hour. As I watched the process a little bit more and was listening more deeply to the music, I said to Ian, ‘You should have synths in your band.’

[Laughter]

He said, ‘Well, who’s going to do it?’ I said, ‘I’ll give it a shot.’ And that was the first time I really started playing. So, I started learning while I was in the band. I feel like I always had a feel for music but just not music theory. That can be an advantage because you don’t know the rules you just know the feel.

But you’ve done a lot of performance art and poetry before, so you were kind of used to performing?

PASCALLE: Yes, used to the idea of a creative space, and very interested in creativity, poetry, sound. I really loved playing with sound, with poetry as well. As I kept playing in The Stress of Leisure I increased that in my poetry as well.

I’ve always wanted to ask both of you what kind of music were you listening to growing up? We’ve talked about music a lot but never that.

IAN: I grew up in Western Queensland, and I remember the influence of Countdown in the ’70s. I was always really into watching it, even as a four-year-old. Through that show came artists like Sherbet, ABBA, Bob Seger—I’m not even sure how they came through Countdown—but there were all these artists of the ’70s: Dolly Parton, of course, Kenny Rogers, and Slim Dusty, who was everywhere. There was a strong country music influence; Slim Dusty and Johnny Cash would play on the rodeo speakers. At community events, you’d hear a lot of Slim Dusty, Johnny Cash, and others of that ilk. So, you’ve got that kind of music embedded in you.

It was exciting watching shows like Countdown and seeing glam artists, people in glam suits like ABBA, which contrasted with what you were surrounded by. Then there were the country rockers, like John Denver, Kenny Rogers, and Dolly Parton. So, there was this multitude of different influences. When you looked at AC/DC, for example, they might seem cartoonish now, but as a kid, they felt dangerous and masculine—songs like ‘Jailbreak’ and ‘Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap’ really stood out.

I remember listening to a lot of compilations, like the Bullseye! record. It started with John English’s ‘Hot Town,’ which was, in a way, like a country ballad mixed with glam disco. It was weird but unforgettable. And then there was the Bat Out of Hell album by Meat Loaf, which was a big discovery for me as an eight-year-old. All that ’70s music just seeped in. It was a long way from London or New York and the kind of universe we inhabit now, but that was my ceiling back then.

How then does that childhood music go to where you ended up?

IAN: It’s a respect for the fun of music, because a lot of people get really serious about what music is. But when you think of it as a kid, you’re looking at the fun angle—like ABBA. A lot of those songs are just outright fun, like ‘Money, Money, Money.’ I used to walk around singing that song. Maybe I was a young capitalist! [laughs]. But I guess the idea is that there’s fun to be had in music, and it’s a shared experience when everybody likes a song.

What I find really interesting is that even people who are deeply involved in underground or indie scenes will unite when a popular song comes on. That’s what I think is the fun element—it’s recognising that music can be, at its core, a lot of fun.

Totally!

PASCALLE: My mom was really into music, and she was a singer who put a lot of value on singing quality. So, the artists we listened to were people like Kenny and Dolly, Linda Ronstadt, Air Supply, and Anne Murray. I remember thinking that if you’re a good singer, that’s really important.

The radio station we would play in our house was 4KQ. We weren’t really wealthy, but we had a few tapes—maybe the Grease soundtrack and Annie the musical. With cassettes, it was that whole thing of playing them over and over again: stop, turn it over, and play again. I knew these songs by rote or by nature because we listened to them so much.

I remember our neighbour, Nava, introducing us to The White Album by The Beatles, and it just blew my mind. I thought, ‘Wow, this is amazing!’ Throughout my life, it’s been a gift when someone says, ‘Have you heard this?’ or ‘Have you heard that?’ I remember hearing the techniques and just going, ‘Oh my god, they’re amazing!’

It’s that whole experience of people in your life randomly giving you the gift of opening your mind. That’s pretty exciting.

Yeah. I grew up listening to a lot of that too. I had four older siblings, and my parents, who all listened to music. When The Highwaymen came out, my parents went to see them. My mum took photos of Elvis on the TV when he performed. A sister started a Bay City Rollers fan club. I’d watch Annie, The Wizard of Oz, and The Rocky Horror Picture Show after school everyday.

PASCALLE: And theret’s something about repetition that is important maybe to a childhood journey.

IAN: It’s interesting because our family used to come down to the Gold Coast for holidays around the summer, and I always remember a record shop in Pacific Fair that I was really excited about going to because I had a record in mind: Racey’s Smash and Grab. There was also KISS’ Dynasty. I remember really wanting those records. They’re some of my earliest memories of my passion for music—buying, actually being a consumer of music.

PASCALLE: I was more of a mainstream consumer, loving Gloria Estefan, Mariah Carey, and Salt-N-Pepa. There was no real exploration beyond what I was being fed. Then, there was Mojo magazine and things like that; you would go there, and that was kind of setting you up to be a music lover. The first thing I bought myself might have been Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

IAN: I bought that as well.

PASCALLE: Knowing that completely off by heart, and Whitney Houston.

IAN: My buying habits in 1982-83, when I was in upper primary school, included Michael Jackson’s Thriller, Prince’s 1999, and Hot Chocolate’s Greatest Hits. It really blows my mind to think about my taste because those are the things I really wanted to buy.

We own them all!

PASCALLE: There’s that story about you, Ian, and Billy Ocean’s ‘When the going gets tough’ song.

From Romancing The Stone.

IAN: You’d listen to the Top 40 late at night on your pillow. I remember the song ‘When the Going Gets Tough’ was like number 38. I turned to my mate Steve and said, ‘Mark my words, this is going straight to number one.’ [Laughs]. And next week, it got to number one! He turned to me and said, ‘You were right, Powney. It went straight to number one.’ It’s the only time I’ve ever predicted a hit. Yeah, and it was from Romancing the Stone.

I love how we all listen to all kinds of music.

PASCALLE: I’ve never had that thing of anything is out of bounds from listening to I might not love it but I’m open to and have a initial you know fundamental respect that people make music whether you know whether it’s my cup of tea or not .

That’s why I hate reviewing stuff. It’s just one person’s opinion, and often—at least with the reviews I read—the writer is uninformed, has limited reference points, tries to get too fancy or intellectual, or attempts to be gonzo, or doesn’t really try, like parroting the press release. I always think that anyone who makes something deserves credit. It’s hard to put a lot of yourself into something, put it out there, and be vulnerable. The attitude that someone else’s preference shouldn’t exist is rubbish. I’ve seen a lot of reviewing that is more about someone trying to have power themselves than actually anything of value.

PASCALLE: I have a pretty strong attitude when I read someone rubbishing a piece of art. I go, ‘Why’d you do that? What’s the point in doing that?’ There’s more value in someone telling me, ‘I love this for this reason,’ than in saying, ‘This is bad. I agree with you that “good” or “bad” shouldn’t exist; it should just be art.

IAN: I guess the theme is open-mindedness. You can go into creating stuff and be very closed, holding on to your ideas really tightly. I kind of did that initially with songwriting and, as it’s gone on, I’ve found that the fun side of making music is giving up all those preconceptions of what you bring and being open to other people’s perspectives within the group you’re working with. That’s fun, even though there’s still an imprint of yourself in the lyrics and guitar lines and stuff. It’s kind of coming to terms with one’s own ego.

PASCALLE: And what happens when you let go to see what happens when people take on different ideas?

IAN: Pharrell Williams talks about trusting a producer. I think he had a chat with Rick Rubin or something, and they talked about trust. He goes, ‘When you’ve got your partner, you trust that. When your partner says that you snore, you snore.’ So, if you’re working with a producer and they say that your voice would sound better in this context, there’s a level of trust: do you trust what they say to do it like that? That’s what I mean when I say being open-minded is about listening to other people and saying, ‘Yeah, I will try that.’ Just be open to it; that sense of openness is quite scary, I think. There are some artists who are really courageous in going there, but there are also artists for whom that would never work. But, yeah, I just think that the older you get—especially for me (though that could be a generalisation)—it’s just about being open to, ‘Hey, you’d sound good doing this; why don’t you try it?’

PASCALLE: Often, when you try something, it can lead to something else, and that something else wouldn’t have happened had you not tried the idea in the first place. So that whole ‘let’s explore what happens when we do collaborate.’

When we saw you out at a show, you talked about how you’ve been jamming and writing these songs, and mentioned that this album is more of a collaborative process…

PASCALLE: That was the last album.

IAN: Yeah, definitely the case with Faux Wave. It’s still collaborative with this one, but I was talking more about how there are more guitar shapes, and they’re easier to play. I brought in more of those sorts of guitar lines instead of what I was doing previously, where I was playing off everybody. This one’s a bit more about the idea than expanding.

PASCALLE: Faux Wave was purely collaborative and Ian would say bring in a line, bring in a line, we see where it goes and we jammed our way to those songs on that album. We didn’t do that this album. This album almost, if you go back to the Stress of Leisure discography, it kind of has ties to Ian’s songwriting in those earlier albums because this one seemed to me that Ian brought more ideas.

IAN: I was fighting against that because I like the collaborative model of what happens when you do this.

PASCALLE: We still collaborated in bringing the songs to life, but this album, in particular, is more Ian’s songwriting-driven.

I’ve noticed that there are different themes and imagery that carry over through your albums Obviously, politics is a big thing.

IAN: Yeah, I’m heavily invested in noticing what’s going on.

Your songs seems to be more observation than super personal. But there is personal too, you mentioned a song your wrote that was inspired by you walking in New Farm Park.

IAN: ‘Unhappy Wedding Photographer’. People smile or laugh when they hear that title because they can relate. They’re painting the picture already for themselves with that title. It came out of, I was living in the UK and came back to Australia. I was already aware of the politics of Australia and where it was, but with how it is, and that Liberal Government had been in power for, six years by that stage. You could see there was a change to the country; it got a bit meaner.

It was really interesting because it came from that era of [Paul] Keating around ’96, where there was sort of, progressive hope. Then when I came back, I was coming from a really cosmopolitan place full of so many different people, such as London, and coming back to Australia and just looking at it. You get this knee-jerk reaction because you’ve just been in a big city in the world, and you’re coming back, and you’ve still got those thoughts. But just looking at the entitlement and the small-mindedness of what this country can be, I’m saying it could be so much bigger.

I was thinking, and it was kind of judgmental. I don’t like to be judgmental, but I couldn’t help but feel it. It was definitely a feel of the country. So when I’m writing that song, I’m going right back to that point, and it feels like it’s at the start of what the Stress Of Leisure is. It feels like that’s where I started. A daily walk through New Farm Park, seeing people do whatever they’re doing, and just total ease with what the country was like.

You’ve had the children overboard thing, and all that stuff was in full swing, so all those politics were really rife and vicious. So just with that, I’m looking at a different life, feeling like an outsider, and I guess that’s where it comes from.

PASCALLE: For me, ‘Unhappy Wedding Photographer’ is very cinematic. I feel like it’s the narrative of the subject of the song, it unfolds and I feel like that’s a real style of your songs.

IAN: It’s intentionally grotesque. But it’s cloaked in the humour of it.

I like that your songs are about heavy or important issues but there is a humour, which makes them more palatable and relatable so people will kind listen more.

IAN: Mm-hmm. Yeah. The country’s changing again from what it was then but I definitely feel like it’s an inception song For The Stress Of Leisure.

PASCALLE: And then, It Goes Away With The Heat has many songs on it that are responding to the world right now.

For example, the title track. It was inspired by something Donald Trump said?

IAN: Yeah [laughs].

PASCALLE: He was saying that COVID goes away with the heat.

IAN: It was such a good title because it’s got a local reference: we’re living in the subtropics, it’s hot, and then it’s got the global references, such as global warming. You look at all the temperature graphs, and they seem to be going up from all the different readings. You’ve got a good way of putting it, Pascalle.

PASCALLE: I feel like It Goes Away With The Heat, capturing a local experience as well as that global experience—the tensions of the world at the moment, which are just almost unbearable; the climate is unbearable.

IAN: I had a friend remark to me—he’s not at all political or interested in politics—and we were just driving somewhere. He said, ‘Yeah, it feels like everything in the world, like something that’s happening on the other side of the world, matters to us now, and everybody gets really upset about it at one time.’ I went, ‘Wow, that’s really interesting; that’s actually true.’

There are a lot of things happening in the world that we feel way more connected with than we may have three decades ago, and maybe that’s the insularity I was talking about. We’re at a weird moment in the world where there’s been this globalisation, but I think there’s a knee-jerk reaction against globalisation in terms of the way economies are going—tariffs and being closed-off economies—while at the same time being influenced by everything that’s happening. So it’s kind of this paradox we’re in at the moment.

PASCALLE: I also feel that you’ve got the media and politicians really wanting us to have blinkers on certain things. But we can’t have blinkers on certain issues because they’re visible to us. We can see what’s happening in Palestine and Lebanon; we can see what’s happening in the climate crisis all over the world because it’s being covered.

IAN: We can see what’s happening in the Northern Territory.

PASCALLE: The other reference is the heat, which is police.

IAN: Queensland has the Fitzgerald inquiry and the whole white-shoes gang of the Gold Coast, and everything has always been what I’ve grown up with in Queensland. The whole Joe Bjelke-Petersen government, the influence of which still permeates Brisbane to this day, I believe, and a lot of people who were involved within that government—observers, participants, critics—are still alive and active. It’s still a real history, and it feels like it still has a way to play out in terms of where we are in the world. So it’s forever interesting.

Before, you were talking about how, when you came back from the UK, you were observing everyone going about their business and doing what they do, while all these other terrible things were happening, and people kind of just accepted it. That’s something you still see now with everything happening on a global scale. But then it’s also hard because sometimes you feel helpless in the face of such massive events, like the genocide and wars that are happening.

PASCALLE: I wonder if things like, you know, people taking photos of their food and having this social media presence is a coping mechanism for the trauma of the world today. It certainly could be a response to that, a coping mechanism.

IAN: It’s the stress of leisure.

It’s so interesting that we live in an age where we can see what’s really going on in places by everyday people posting about the situations. I find it very hard to trust mainstream media.

PASCALLE: Yeah, I feel the same way. I feel that it is really hard to ignore the fact that the media is biased in its representation.

Yes, you have to just look at the language they use.

PASCALLE: We’re critical thinkers. You have to look through the language and see, if you’re positioning this person as not human or dehumanising someone in the way you’re reporting, then it’s very important for us to hold them to account.

IAN: I’ve got a heavy blanket of cynicism but I’m also a wide-eyed optimist. I think that communities can work together really well, and I’ve seen what happens in disaster situations, like the floods that occur in Brisbane. People come together, and those who don’t normally talk with each other want to connect; they want to help. There’s inherent good in a lot of people. We’re just continually distracted by stuff which we don’t need [laughs].

PASCALLE: And we’re controlled by the systems in place as well.

IAN: There are countless tensions and distractions that often keep us from living.

Musically a lot of songs on the album do have tension and tell a story, you’ve captured that feeling in sound.

IAN: I always felt we’re always adjacent to some sort of discomfort or hostility, and that’s been an ongoing thing. There’s something happening, and it’s kind of very uncomfortable. I think that’s part of life: dealing with discomfort and how much we attenuate that.

PASCALLE: Maybe musically, too, the bands, as a style, tend to fit into each other, not over each other. We don’t tend to layer over each other; we fit in the spaces in between each other. So, there is a tension in that as well, in between the instruments.

The second track on the album is ‘Expectation Confrontation.’

IAN: That actually came from, I guess, being around a lot of anxiety, and it’s really a song about— it stems from hyper-vigilance and reacting to potential future situations. It’s also like references to bullying and everything in that song, but I feel I come across more people who sort of struggle with the day-to-day.

PASCALLE: The stress of what is potential.

IAN: Being around people who were blanketing and putting a filter on stuff, which, you know, this is a potential thing, and negotiating the world through that. At once, it’s humorous, but also it’s real for a lot of people in the world [laughs]. Especially when you go online now, and it’s full of outrage and tension, and people are brought to your attention who you normally wouldn’t have any contact with. All of a sudden, we’re exposed to the person in the dark corner of the web, whereas we’d usually have to go to a bar and sit near them to hear their theories, but now they’re telling us off on the online thread. Sometimes, you put something out there and you go, ‘Well, I’m expecting some form of pushback with this.’ This constant experience of hyper-anxiety, when you actually do say something, especially in the media space, comes back against you.

PASCALLE: I was seeing that Moo Deng, the hippo, and the absolute joy Moo Deng is bringing everybody. Then I saw a post from another zoo, kind of competing, saying, ‘Our hippo is better,’ and I was like, that is typical internet—to go from something nice to challenging them.

IAN: A hippo confrontation.

[Laughter].

The internet is and technology is another theme often in your work.

IAN: If you drive around this city, any city, and you look at the passengers in cars, nine times out of ten, they’re on their phones. It’s just uncanny. It’s just what people are doing now; it’s like everybody is living these online lives. Next time you’re out and about and you happen to be a passenger, look at the other passengers.

PASCALLE: But we write about the internet, not only from the users perspective, but also from the tech bros. Looking at those who are controlling that space.

IAN: References to Bezos, Musk, and Branson—though he isn’t really a tech broker; he’s rich. There’s this thing that’s increasingly being referred to as techno-feudalism, especially in something like Amazon, which is basically just charging rent for doing nothing. It’s like the old form of feudalism. It can be described a lot better than I can by other intellectuals, but that word is kind of part of my thinking in that song. But also, it’s the fact that it’s coupled with the simple joy of enjoying a coffee. For me, I love a coffee, and it’s that meditation of 15 minutes before the tech world ruins it. You’re kind of like you’re online, and then your high is slowly disintegrating into some online fight that you’re looking at, and it keeps you engaged for another 10 minutes or something.

It’s an unusual chord-y song for us. Another fun song to play cuz it’s got all this space in it. Pardon the pun.

[Laughter].

But there are stops and elongated spaces within it, and it works in that sense. It’s an odd song structurally. John Lee, who runs Phaedra Studios and has probably recorded a lot of bands that are on Gimme, is a really good listener. If he’s not vibing on something—like if he doesn’t feel it—because we knew him after working with him once, we came in quite prepared. If we did a song and we got all the way through and John didn’t make any notes on that song, it was a clear signal to us. That’s great. We got we got another one through! It was the only song where he said, ‘Let’s try stuff.’

PASCALLE: He picked out that we wrote it really close to going down to record it. He picked that it wasn’t fully formed yet.

IAN: He basically stretched it out. It was this enclosed, dense song, which he then basically helped us craft the space in it. So all those elements were there.It’s fun to play now because of that.

It was recorded over five days?

IAN: Yeah. We recorded 11 songs in five days and so 10 songs made the album. Most of the vocal takes are all on the last day, so it was kind of pretty heavy going.

Your vocal is different on this record. You’ve still got all the character but it sounds like you’re almost at peace with it. Maybe you’re more confident?

IAN: It’s the first album I’ve listened to where I can hear my vocal and go, ‘Oh yeah, got that right.’ Maybe it’s all about doing it in one day, and that one day I was in the right headspace. We inhabited these songs for a long time, and they were the songs we built over the pandemic. We were kind of arriving at them over a long period of time, so spending a lot of time with them helps. But yeah, I see where you’re coming from because I look at it, and it doesn’t feel pushed or out of place or like it’s trying to vibe on something that isn’t already there in the attack of the vocal.

PASCALLE: Because there wasn’t time to waste as well, you were a powerhouse that day.

IAN: It was just bang, bang, bang, bang.

PASCALLE: That might also suggest that you felt really comfortable with the lyrics as well?

IAN: Yeah.

Comfortable in what way?

IAN: Like, ‘Unhappy Wedding Photographer’. I have inhabited that song for a long time. The other songs just felt right, syncopation-wise, because a lot of my vocalising is, like everything, I guess, syncopation. It’s hitting the mark at the right time, and I think it just happened that that mark wasn’t—it’s kind of felt in line in every song. It wasn’t complex.

PASCALLE: My experience is that when Ian and I write lyrics together, it has to feel right in his mouth. If I’m writing something and in the past that’s been difficult to write for his mouth.

IAN: Pascalle really developed the melody line for ‘It Goes Away With the Heat’. She wrote out a whole lot of phrases, and that kick-started it, working out the syncopation of the melody in that song. Pas is an experimental poet; she can deliver lines and uses a lot of cut-up techniques, where she combines different phrases and rearranges them. I think ‘Expectation Confrontation’ was largely Pascalle’s work and I’ve added little things like ‘Maybe take the long way home.’

PASCALLE: When we’re rehearsing, Ian improvises like…

IAN: Like, I’m speaking tongues.

PASCALLE: He’s speaking gibberish, and then we record the demos. I listen to how he’s phrasing, and I feel like that’s something I’ve done better this time. When we do that, I’ll go, ‘We’re keeping that line!’—like, I’ll hear something and think, ‘That’s in!’ So I make sure it stays. I think it’s pretty fun to listen to the gibberish and try to work out what might fit in there.

IAN: We’re heading for an Elton John/Bernie Taupin writing relationship.

[Laughter]

Just kidding!!

PASCALLE: Yeah, no, no.

Where did the title for song ‘Man Who Make A Racist Comment’?

IAN: I’ve had for a long time and that would predate even probably around Achievement time that would have come out.

PASCALLE: It sounds like a Betoota Advocate headline.

IAN: You read it as a headline. It could be a Courier Mail headline, really [laughs]. But that’s where the starting point for that song is, and the words kind of flowed out when we were playing it. A lot of the building blocks for that song just came out spontaneously. We worked on it a little bit at home, but yeah.

We face the situation where, if you go outside the inner city and actually venture into some regional areas of Queensland, you might find yourself in a situation where someone will come and say something…

PASCALLE: However, having said that, the inner city does racism in a very different way. So, the song is not about any particular context; it’s about the micro-aggressions, the different oppressions that are found in day-to-day life.

IAN: But what I’m trying to say is that it could be the outer suburbs. The inner city is very cosy, and it can be very comfortable with the sentiment that it’s great and all that sort of stuff. I’m generalising—it’s a big generalised thing. What I’m saying is, you go out into a situation where you’re confronted with racism, and a lot of people are in shock. In that situation, you do nothing, or whatever.

PASCALLE: Or if you do say something, then that person has that white fragility response of objecting…

I find that a lot of racist people often don’t even realise they’re being racist.

PASCALLE: Yeah, that’s right.

IAN: Once again, the song is observational. I’m trying to take judgement out of it, even though it’s a big judgement in the sense of what it is. People can take extreme exception to it straight away, as soon as you say the title. I realise the tension in that, but the tension is within the song—these micro-situations you encounter, but then there’s the macro. So the first verse is the micro, and the second verse is the macro. You know, corporation charity balls—throwing them under the bus, why not?

[Laughter]

It’s being adjacent to hostility that we face. It’s something that is continually in the culture, unfortunately, and there’s a lot of world-weariness to it as well, because it’s something that’s been there—it’s just existed for eternity.

PASCALLE: It’s such an easy take to to cry about being called on your behaviour you know. I like the song because it does point that out, it points out that sometimes people resort to calling themselves a victim when they been out of line.

IAN: It feels like a long bow, but I think of the title as something like the Jam’s titles, such as ‘Down in the Tube Station at Midnight’ or ‘A Bomb on Wardour Street.’ In the same vein, it’s a really strong, descriptive phrase that you can repeat, and it becomes something. So there’s that as well, in terms of the songwriting. They’re not a group of words you would expect to be drawn into singing as a refrain.

PASCALLE: Because it’s quite a catchy song, I think. People have come up to me and said, ‘Oh, I can’t get that song out of my head.’ And it’s kind of like… that’s a funny phrase to be the thing that’s going around and around.

IAN: I love that thing of starting a song with the chorus. I know a lot of Chic songs, and Nile Rodgers would always start songs with that. Starting with the chorus sets up what the song is, and I’ve always loved when you try to flip the script—starting with what is the hook, or if there ever is a hook, and then going from there.

There are all these references, I think, when you’ve been writing songs. That’s the element of fun we’re talking about before—there are so many fun elements when you’re a curious music listener. You listen to something and think, ‘Oh, that’s fun. I like the way they did that.” At the end of the day, they’re all playful. I know we’re talking about a serious subject here, but the songwriting, in the sense of where you place particular things, is playful.

You made a video for the song!

PASCALLE: We filmed in our community space with Ben Snaith (Orlando Furious) and Asia Beck. Phil Usher and Beáta Maglai were a big part of tit too. Bea played the guitar, and Phil also helped with camera work and creative input. It was pretty low-fi. We got the silver backdrop and taped that up, and the masks we had in mind already. I found them online, and you had to buy a bunch of them to see if they were going to work—and they did the trick. Ian had the wig on, and it reminded me of those 70s variety shows, where very inappropriate things were said.

IAN: It was like Tim Heidecker.

[Laughter]

PASCALLE: Throughout, we weren’t trying to point the finger at ‘this is what racism looks like.’ We wanted to keep it wide open and try to say that racism can look like anything. We were looking for this extra thread to kind of go through it, and Ian thought of the pillow, which really symbolises that fragility.We’ll be right back.

IAN: Poor guy. Hugging his silver pillow. The red writing is meant to be distraction, that’s the heart of racism as well. We don’t want to go too much into it otherwise you sound too much like art wankers.

[Laughter]

I didn’t get to ask you about the imagery of ‘Unhappy Wedding Photographer’ before; where did it come from?

IAN: I love the rose beds in New Farm Park. People are getting photographed over there, so you immediately get the sense, and I’d observe people in the park. There’d be all these guys just standing around together, and they had all their sunglasses on their heads. I went, well, there you go. That’s where the title comes in—it’s just observation. You see these scenes playing out, and they happen too many times to count. So, you’re in these elaborate suits, and they’ve got sunglasses on their heads. That’s just the detail… nothing’s quite right when you look at the scene.

PASCALLE: It makes it like a movie because then he introduces the unhappy wedding photographer after setting that up. So it’s kind of almost like stage directions—enter this character, enter these characters.

It leads back to the idea of the wedding, what the wedding represents as well. You know, it’s supposed to be the most perfect day of your life; you spend a shit ton on it, and the photographer is accountable for capturing everything of the best day of their life.

IAN: It’s a lot of pressure on the photographer, and it’s not a stretch for them to be unhappy, yeah, because of all the demands made on the day and the tension and stress around it.

PASCALLE: Whenever there’s a big family event, like a big family event, it has its own drama. So, Ian talks about it being in the eyes—it’s in the eyes of the photographer, it’s in the eyes of the subjects of the photos. You know, there’s a lot of drama going on.

IAN: You get a lot from people trusting their intuition about micro-expressions in people’s eyes and faces, and the camera can capture that. The camera can capture that micro-expression when you’re looking pretty upset with somebody. That’s what I think the fun is—focusing in on the eyes.

What can you tell us about song ‘Dead Man Golfing’?

IAN: It’s another Trump reference. It still goes on, he’s still golfing. It was a phrase from a newspaper article that Paul Curtis texted to me. I thought, ‘what a title!’ We went to rehearsal and it just came out and that was it, like, wow, the system works. It was a real collaborative effort where everybody’s got a different line and they had these ideas and they just kind of meshed together, bang, done. At the end of Trump’s presidency, and there’s that shot of him walking back from the chopper or on the golf course where he’s really quite forlorn. That’s where it comes from. There’s the whole thing about golf and the prestige of golf.

The song ‘Hot Lawyer = Hot Song’ carries through a theme you’ve explored on other albums, that of a lawyer.

IAN: We’ve got something for lawyers, and hot lawyers [laughs]. It’s fun to play with these concepts because it’s all about the idea of contracts. Whenever you’re entering into a contract, it’s immediate and unnatural. You used to have your word, but now you can’t rely on that anymore—you have to write it down and sign it. This need for written agreements is what stems the legal profession. The legal profession is making so much money.

PASCALLE: And, in absurd ways, like the defamation cases where it just actually makes that person look really bad.

IAN: It’s related to the continuum of the music industry. Whenever lawyers are involved, things aren’t great. I think of Ian MacKaye and Dischord Records—he doesn’t do contracts with people; it’s just an open agreement. I reflect on that in terms of the music industry.

PASCALLE: What would it be like if we operated that way?

IAN: Yeah, and like getting a lawyer to look over an agreement that you’re making with somebody and I guess whatever you have digital aggregation like with Spotify or iTunes, we are signing agreements ostensibly but it’s just the relationship of you and your music within the legal…

PASCALLE: Talk to my people.

IAN: Yeah. In order to be really big, you need a hot lawyer because if you’re going to be in that business model, that’s where you get the big songs. I guarantee all the big songs of the world, there’s all legal representation behind it. That’s the way I’m looking at it. It’s my next Big Sound keynote.

[Laughter]

You gotta get a hot lawyer, everybody! [laughs].

On this album you’ve done an R.E.M. cover.

IAN: It just made sense. We’ve played that live multiple times before, but we thought, because Jane has this really moving bass line, it would be good to capture it since it feels a bit different. It’s taken it from a minor to a major kind of key, and the attack of the song, along with the bass, moves around. It was interesting, and I think if you’re ever going to do a cover version, you should deconstruct the original and do your own thing. This is a great example of deconstructing the original, and we enjoyed the result. It has these Television-esque guitar lines mixed with a funk guitar line.

PASCALLE: I guess it’s disco kind of.

IAN: The skeleton of the hook in the R.E.M. song is great—just throwing that little line in the chorus. Those little things in the open space felt very New York disco, kind of— not no wave, but it has that underground vibe to it, which attracts us.

PASCALLE: Ian and I love covers.

IAN: The lyric is about a sociopath, and the times are right for sociopaths. This is the time!

[Laughter]

That lyric is a really simple, direct lyric, and it’s not about love. So that’s what I like, because we don’t really do love songs, and this is kind of like not a love song either.

PASCALLE: But also known for being played in contexts where people play a lot of love songs.

What about your song ‘Silent Partner Jam’? I took that to be a love song.

[Laughter]

IAN: A silent partner could be a business relationship too.

PASCALLE: Well, there is love in every one of the songs.

IAN: I think of ‘Silent Partner Jam’ as being about the guy who has a silent partner and runs a law firm in the suburbs. They eat at restaurants by themselves, disconnected from society, and there’s a lot going on as they try to connect with the world.

My interpretation was so much more lovelier and romantic than that.

IAN: Stay with that.

PASCALLE: But also like it’s a slinky little song and I think that’s enough if it brings the slink, then that’s a love song [laughs].

IAN: That song, I feel, has a lot of the humidity of Brisbane in it. I feel the darkness and the humidity in that song in the subtropical locale. I feel very embedded in it. Meanwhile, ‘Unhappy Wedding Photographer’ is in New Farm Park, while ‘Silent Partner Jam’ could be in The Gap—somewhere lush, green, and sticky.

I love that, as we were talking about before, the heat can be so many things throughout your work.

IAN: I love bands from Athens, Georgia. There’s R.E.M., Pylon, the B-52’s, and Of Montreal too. Neutral Milk Hotel also has an association with Athens, along with the Elephant 6 gang. There’s so much creativity within that scene, and it’s kind of weird, freaky, and full of misfits. They’re people expressing themselves artistically, and they don’t fit in with the mainstream. They’re not doing the same thing as everyone else—they’re just doing their thing.

There’s an idiosyncratic quality to it, but it’s also embedded in the Georgian heat. You think of that place, and I mean, R.E.M. had the kudzu on all their album covers—the Murmur album covers, with that plant or shrubbery, that vegetation. That feeling of the southern heat. I relate to that. Like New Orleans has the humidity and stickiness, and the musicality, and Brisbane has those elements too. It feels like we all share this experience in different ways around the world. What is that? How does that humidity and heat and location embed itself in our music?

PASCALLE: I’m going to go in a completely different direction in response to your statement about the different meanings of heat. The other day, I was boiling the kettle, and our kettle is one of those see-through ones. I was just standing there watching it, observing the water move from still and room temperature to a rolling boil, and then the steam coming out. I had this little epiphany—wow, that’s like an emotional range of what we go through from moment to moment. We move from stable to heightened, to elevated, or even ecstatic. We go through all of those different levels of heat.

Follow: @thestressofleisure. Check out thestressofleisure.com and listen to their music HERE. Watch our TSOL live videos HERE.