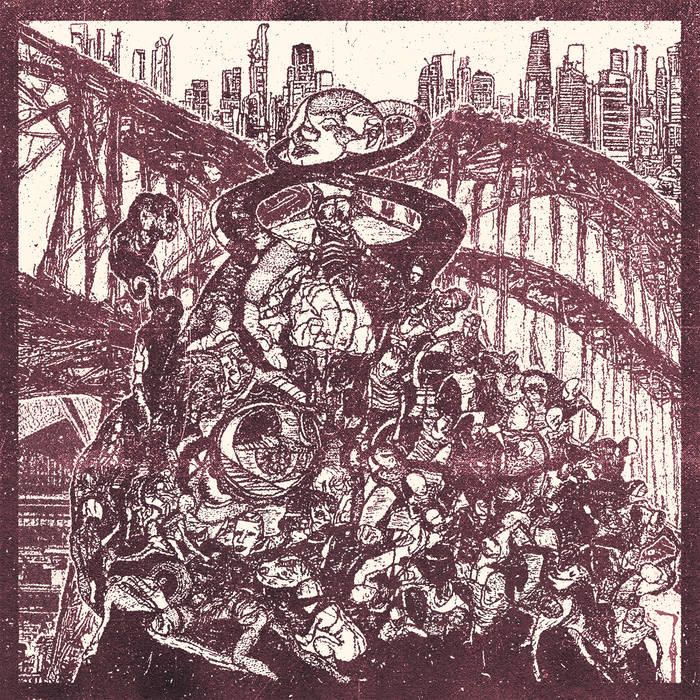

Negative Gears’ Moraliser stands out as one of the most exciting punk albums to emerge from Australia in 2024, brimming with turbo-charged aggression and a time-bomb of tension. The Sydney-based band has crafted a record that not only captures the raw energy and intensity of punk but also layers in thoughtful, pointed commentary on the issues plaguing their city. From selfishness and materialism to a shallow obsession with wealth and status, Moraliser takes direct aim at Sydney’s desire to emulate America—critiquing how this trend often brings out the worst in people. Yet, amid the biting criticism, the album also celebrates the resilience and unity of Sydney’s underground communities, presenting a complex, vulnerable reflection on modern society.

What sets Moraliser apart is Negative Gears’ ability to summon intense emotions while dripping with excitement and urgency. The album resonates as a commentary on the cultural zeitgeist, capturing the frustration and hope that define the band. Drawing from years of personal growth, Negative Gears has found the motivation to push through, finishing an album that speaks not just to their local scene but to broader cultural discontent. Creating with no rules, their music embraces personal exploration and community over chasing status—Sydney has truly shaped this record, both in sound and spirit.

I understand you work at Sydney Theatre Company, right?

JULIAN: Yeah, I do. Four of us do—me, Charlie, Jaccamo, and Chris. Four out of five of us are there [laughs].

It seems like it’d be an interesting place to work?

J: It is interesting. It gets the bills paid and most of the people there are pretty cool. The production end is all carpenters, props makers and painters Everyone is creative to some degree.

It’s such a millennial stereotype to say “creative”. But the irony is that, at our end of the building, we get to make the stuff, take it to the theatre, set it up, and put a set together, or paint it. You get no credit for it. It’s pretty much exactly like the DIY scene, in the sense that you just do it with your peers. Your peers respect you if you’re good, but no one else gives a shit [laughs]. The people who are called the “creatives” are the designers who come in and give you their design, and then they talk about stuff like, ‘No, no, paint that black—blacker’ or whatever [laughs]. It’’s fun. Chris does a lot of painting and Jaccamo, he’s with us in logistics; we run a lot of trucks and help put up the sets.

It sounds a lot like my job as a book editor, you do a lot of work behind the scenes and no one actually knows how much—in a lot of cases, a lot—you’ve contributed to a creatives finished work. And, as you said, you don’t get credit for it, which for me is fine. I’ve always preferred working behind the scenes.

J: A lot of people who are into the underground or slightly outside of art shy away from making that their job. So it’s nice when you can use the skills you’ve learned in your art or your passion and then, effectively, make your deal with society. I remember my mum would always say, ‘You take the skills you’ve got, and as long as the hours and the pay are all right, you make your deal.’ You might not be getting everything out of life; your job might not be what you live for. But if you love the stuff you’re doing outside of work, at least you can be happy with the deal you made.

Totally. I’ve always had jobs to pay the bills and then all the other stuff I do, like Gimmie, we just do it for fun. We do it because we love sharing music and stories with people. There’s quite a few writers out there that like to be unnecessarily critical of things and in fact make try to make a career and persona from that, they think they’re edgy and cool. I’d rather write about what I love than what I don’t, and share that.

J: That’s the difference between things that have impact and those that don’t, in a lot of ways. Like, all that Vice stuff, and all that muso journalism that was BuzzFeed-y, clickbait-y—it’s pretty much all dead. I remember around 15 years ago, that was the main way you’d hear about so many things. Now all that stuff is gone. The only things that remain are done by people who love to do it.

What got you on the musical path?

J: The first underground band I ever saw was Kitchen’s Floor in Canberra. I’m from Canberra—me, Charlie, and Chris all are—we went to school together. Chris and I saw Kitchen’s Floor when we were about 15. They played at the Phoenix with our friends. Kitchen’s Floor was kind of like the moment of, ‘Oh shit!’

Everything else we’d seen up until that point was stuff like The Drones, or various bands playing around pubs. But Kitchen’s Floor had this vibe—we were into The Stooges and Joy Division—so it was the first thing that had a bit of that kind of ethos. It was one of the first things that really clicked for us.

Bands going around Canberra too—Assassins 88, Teddy Trouble, The Fighting League—seeing them was sick. Melbourne bands came too, like Pets with Pets. You look at that stuff and you go, ‘Oh, I could do that.’ We already knew we could play; we’d been in little scrappy punk bands. So we formed a band at Tim from Assassins 88’s house. We were around at his place, and he was like, ‘You guys should have a jam.’ We had one, and he was like, ‘All right, you guys have a gig next Wednesday.’ And we were like, ‘Oh shit!’

Was that Sinkhead?

J: No, no, no, that was when we were like kids. We’re all 32 now. That was when we were 16. Sinkhead was when we moved to Melbourne.

I moved when I was about 18. Did the whole classic ‘go away to Europe for a year, find yourself’ thing, and then came back to Canberra. But Canberra wasn’t very exciting anymore, so I went to Melbourne and moved into a house with Jonny Telafone, a really good solo musician who does a lot of John Maus-style stuff, but without the influence of John Maus. Charlie and I got together, we were 19 then, and she and Chris and I all lived together. And then we met Jaccamo that same year.

Skinkhead was Charlie, Jaccamo and I initially. Chris was playing in another band, but it wasn’t really doing much at the time. And he ended up moving back to Canberra for a bit. But we basically did Sinkhead pretty much only in Melbourne initially, for four years. We only ended up playing three shows in Melbourne ever, maybe five max. Then we decided to move to Sydney after the Melbourne scene had died down.

When we first moved to Melbourne, there were bands like UV Race, Total Control, and so many other good bands playing, like Lower Plenty. By the time we left in 2016, it felt like there wasn’t much to see anymore. The Tote was getting really monoculture. I remember lots of venues were just 98% dudes in leather jackets with full black outfits [laughs].

Then we started seeing all this stuff popping up from Sydney, like the Sex Tourists with their EP, Orion with theirs—both the tapes—and then The Dogging, Low Life record. There was the Destiny 3000 thing going on too. All the videos of the shows happening were really different. The crowd had colour and it was very diverse.

Randomly, Ewan from Sex Tourists was looking for a housemate. I said to him, ‘We’re thinking about moving to Sydney. We might come up and check it out.’ We went and saw a Sex Tourists show that weekend, and we liked that the entire scene was filled with all different kinds of people. It felt way more exciting and a lot more accepting. Jaz from Paradise Daily Records was putting on a lot of shows at that time, and it felt alive! There were really, really good bands, and it felt more like what Melbourne was like in 2010.

Melbourne had now gotten a bit rock-dodgy. People weren’t experimenting as much, or maybe the ones who were had chilled out and weren’t digging as much. Sydney has a really diverse underground scene. I don’t really know why Sydney does and Melbourne doesn’t. Like I said, Melbourne felt really monocultural, it’s the weirdest thing when the scene’s so big when it comes to punters. But it almost felt like it suffered from it. People who were in big underground bands almost started to get an ego. Like, you’d be talking to them, and they’d look past you. In Sydney, there’s just not enough people in the scene for it to be like that. Everyone knows everyone, and it’s got that real community feeling, which is more what we’re interested in. We’ve never had a huge interest in climbing the cultural ladder of Melbourne or wherever. It had started to feel boring. There were great elements too, but Sydney was definitely more exciting for us.

I understand that, I’ve had people look past me how you were saying. I find it funny when people in local bands can sometimes develop a big ego; I wonder if they even realise it? I find they’re usually the ones who are the most insecure and really care about what people think of them.

Congratulations on your new LP, Moraliser! It is without a doubt one of our favourite albums we’ve heard all year. We’ve been waiting for something that’s truly amazing—Moraliser is it!

J: That’s awesome!

We haven’t been as excited about a lot of music this year so far. There’s some cool things that came out but maybe not as much as previous years. There seems to be quite a few copycat bands around. Like, they see certain bands doing well and going overseas and then they decide to replicate the sound and even sometimes copy their look. Our favourite is people doing their own thing, like Negative Gears.

J: Thank you. I really appreciate it. I mean, I’m sick of this record at this point [laughs]. We put a lot of work into it. At the end of the day, hopefully that shows, that’s all you can hope for. It took us so bloody long to get this record done.

So it’s a relief it’s out?

J: Oh God, yeah. It’ll be even more of a relief when everything is done, because right now we’re in the position where we’re organising the Melbourne launch, and we’re going to go down to Canberra, and then we’re going to do a Europe tour in February next year and play all these songs. But the irony is, we’ve actually been playing lots of these songs for years.

Because the record took me so long to mix, it’s like, in our head, releasing it meant it was done, but then all of a sudden, you have to keep playing them, because that’s the first time people actually really enjoy seeing them—because they’ve heard them recorded. We misunderstood how important that was. Previously, after a show, people would be like, ‘Some of these new ones sound pretty good,’ but now that people can hear them recorded, they’re like, ‘Oh, I love this song now that I can really hear it.’

Why did it take so long to make? What was it that you weren’t happy with that made you keep trying new mixes?

J: Man, there’s lots of factors. I’ve got really hectic ADD, and my attention span goes through these wild cycles with creative stuff. I will hyper-focus on something, like, ‘Okay, I made this song sound like this and it sounded great.’ So I would then go back through the whole record and think, ‘I’m going to make everything sound like this song.’ That becomes my new thing—this song is the one that sounds good, and I’m sure of that.

Then I’ll go back, redo everything, and basically overcook the record. I’ll mess with it too much, and then, in a month, I’ll realise I screwed it up and need to scrap the whole thing and start again. That was part of it. But there was a point where I got better at that. About two years in, I kind of stopped doing that. But for the first years, I wasn’t entirely sure what the sound of the record was supposed to be, because it had really expanded.

The first EP was just one guitar, one bass, and a synth. We knew what every song should sound like—it was really stripped back and simple. There was a bit of arty noise stuff here and there, but I knew what I wanted that record to sound like from the start.

This time, we went in with no rules. When we started recording, my focus was, I don’t want to make a record we can necessarily play live. We can figure that out later. We just wanted to put in the stuff that sounded good. For example, ‘Lifestyle’ has six synth parts. Lots of them are really quiet, stereo-panned, but I knew we’d never be able to play any of that live. We were just trying to increase and decrease the dynamics.

Because we had it so open-ended, part of the challenge was not knowing when to stop adding things. We recorded the bones of the record pretty quickly—in about two or three months. But then COVID hit, and that wrote us off for a whole period.

We had movement restrictions, so Charlie and I couldn’t go to the studio. The whole thing was on pause for about six months. After that, it was trying to wind back up and get back into gear to finish it.

Near the end, it started to feel like it had been going on for so long that it became hard to find the motivation to finish. I was really struggling to wrap up the last 10%. After the whole COVID thing, it had been two years of being in and out, with no one playing shows. The whole scene in Sydney changed over that time, and I found it quite depressing.

All these bands we used to play with before COVID had split up. Bands I loved to see. When we started coming out of COVID, it was an unrecognisable environment. Oily Boys were gone because Drew had moved up north, and bands like Orion, and BB and the Blips had split up too.

Bryony from BB, went back overseas. She was in about five bands, she was in Nasho and a whole bunch of other bands that all broke up.

I LOVED Nasho! I love all the delay and effects on the vocals.

J: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Nasho was sick! Bryony is a powerhouse. Everywhere that she goes, she does that. I think she’s in Berlin at the moment. I’ve seen her already popping up in a couple other bands. She’s a total beast. She’s really good mates with Tom from Static Shock, who is the record label for us over there. It was pretty sick having her here for a year, she pretty much revitalised the scene by herself. She really stepped up and made stuff happen.

So COVID hit and then the scene was really different, it was strange. It was like, can you play a show? A couple of shows that did happen everyone pretty much got COVID straight away. I was just struggling to find any motivation. I got it back when we started gigging again.

We met lots of the young people from the Sydney scene. It was like, ‘Who are these new people?’ We were always younger than the big, dominant Sydney scene from 2014 to 2019—the Repressed Records crowd, Bed Wettin’ Bad Boys, and Royal Headache etc. Now, for the first time, we weren’t the young ones.

All of a sudden, lots of good bands started to emerge, like Dionysus (which turned into Gift Exchange) and Carnations. All the new bands gave me a sense of, ‘I’m not over, we’re not over.’ I thought I was dead. I thought everyone was getting over it.

I knew I’d finish the album, but it felt like the immediacy or the purpose for it dropped a little bit. You write the music for yourself, but releasing it is usually something you do because you want to have a party, play some gigs, and go on tour. Like I said, it felt like so many people around us had stopped, and the community was dying a bit.

It wasn’t like that for everyone, but for me, that was part of what I enjoyed, and it felt like it wasn’t there. Then, it built back up again. And, we got enough juice to get through it.

Growing older, I’ve observed that things just work in cycles. Things ebb and flow and that’s natural. When things change or become a challenging it’s good to keep in mind why you do things, like you said, you make music for yourself. Sometimes people can lose sight of that or they can actually be making stuff for the wrong reasons. It’s your job to work out how you can live a creative life that you’re happy with.

J: Yeah. When COVID hit, you start to think like everyone did: what am I exactly doing here? We’re all getting older, and at the time I was thinking, I hadn’t really ever had a job that I enjoyed. I worked for 10 years at complete shitholes that I hated. It was like, what am I doing?

Charlie had it figured out. She’d gone to TAFE, got into this costume thing, and started making costumes for theatre and movies.

That’s really cool!

J: Meanwhile, I had no idea what the fuck I was doing [laughs]. I think that probably played a part too in why the record took so long. Before COVID I was doing a bit of audio engineering for other bands. I’d record bands and thought, oh, maybe I’ll go into audio, work at the ABC or something.

But my passion for that died pretty hard when I was trying to sit in front of a computer constantly, feeling guilty, trying to make myself finish a record. I was like, I don’t want to do this for work as well. I need to get out of the house. I needed to do something physical because I was too wrapped up in guilt. That was the worst thing. Even though it took five years to mix, it’s not like I took massive stints off. I was thinking about it constantly, every day.

I thought, I’m letting our whole band down too. They’d send me messages like, Hey man, how’s the record going? Are you okay? And so it didn’t ever go away. It didn’t take five years because I was lazy. I was thinking about it and working on it all the time. I was cooking myself over it. Doing it again and again—trying to change the tones, overdubbing the guitars, deciding it doesn’t need guitars, pulling things out, putting things back in again, redoing the vocal takes.

Then there was one song where I couldn’t write the fucking last lyric, the last verse in ‘Ain’t Seen Nothing,’ the last song. I wrote it nine months ago. It took so long to write because I didn’t want the album to end on this really negative thing. I wanted it to have this gleam of hope at the end. By the time I’d done it all, I was in a very different mental headspace, and I was like, fuck man, this album is so dark at so many points. That was definitely where I was mentally when I wrote those songs, but I wanted there to be something at the end that was like—but it isn’t that bad.

I noticed that sense of hope on that song. I think the album reflects what a lot of us feel with all the challenges of modern living. ‘Room with a Mirror’ is a really powerful song. It sounds so brutal; was there a lot going on with you at the time it was written?

J: Oh, fuck yeah. It is brutal. It was definitely in that period of self-reflection or trying to get outside of your box and at the same time hating the concept of trying to get out your box in the first place. There’s some funny lines in that one for sure.

Do you find that writing songs and getting all these emotions, thoughts and feelings out helps you?

J: Yeah, for sure. It’s how I process emotion. Like a 100%. I’ve done it since I was 15. I remember writing a song on my 17th birthday about being 17, and how fucking hard it was, which is a joke now, obviously [laughs].

I write plenty of songs that I don’t release that aren’t for this band that will be me just getting shit out. Some of them occasionally get popped out, I did a random solo tape called Goose ages ago.

Living in Sydney influenced Moraliser. In our correspondence you mentioned gross attitudes, selfishness, wealth, status and obsession.

J: Moving to Sydney is a great way to solidify anti-capitalist views. Living in Melbourne, especially in North Melbourne, you’re in this weird little lefty bubble where it’s like, ‘Oh, they make little bike racks so you can go fix your bike, and the council puts on music events twice a week, and they’ll do an organic market fair,’ and you feel like, ‘Man, Australia’s pretty good, it’s not that bad’ [laughs]. While moving to Sydney is a great way to be like, ‘Man, Australia is fucked.’

It’s bizarre here. Everything is zoned into these six or seven different cities: the Shire, Lower North Shore, Northern Beaches, Eastern Suburbs, Inner West, Far West and South Sydney, and the Hills District as well. Every single one’s its own little city with its own rules—social and economic—because the class distinction is so huge. It feels very American to me, very polarised. The wealth gap is huge. The privilege of the coast is huge, like the privilege of the views, because it’s not as flat as Melbourne; every hill is expensive, every flat is cheap.

I used to live in Dunedin for about a year, and Dunedin was like that too. The tops of mountains were the only expensive places. But Sydney definitely shaped the record. I found it pretty weird, especially since I grew up in Canberra.

Nic Warnock wrote a review of Moraliser, and he said at the end of the review, ‘I think growing up in Canberra informed this, even though it’s not in the presser.’ I asked him, ‘What the fuck do you mean by that?’ And he was like, ‘Oh, just your views are probably inspired by those previous places.’ I thought about it, and yeah, he’s totally fucking right.

Canberra is this weird sort of zone outside of the rest of Australia. I go visit my parents, and there’s a little booklet on the table about what the Labour government—which, by the way, has been in power for about 34 years—has been doing for you. You look at the paper, and it’s, ‘Retirees have been getting together with the youth to graffiti,’ or, ‘We’re putting in a tram,’ and ‘We’ve re-greened this whole area.’ Canberra still has its problems, but it’s a bit of a left-wing bubble. Even though it’s gross in some ways, it doesn’t have the money or the display of wealth that Sydney has.

That was really shocking to me. You don’t see Lamborghinis in Canberra; everyone drives a fucking Subaru. It was quite weird to move to Sydney and be like, ‘Oh, we live in Sydney now, let’s go to the beach!’ And then you go to the beach, and it’s not a beach—it’s not Batemans Bay or Brawley. The beach is a park for rich people, a place where they show off designer outfits and spend their lives looking good. It’s a status symbol.

All of that was really confusing and exciting—not that I thought it was great, but I reacted to it strongly.

We live on the north side now, which is the home of the enemy. When we first moved here, Tony Abbott was the local minister.

For example, ‘Ants’—that song is about living in this apartment. My grandma bought this apartment in the late ’60s. She passed away, but she lived here her entire life after her husband died. It’s this tiny apartment—it’s got three rooms. We’ve been living here for a couple of years now, and the whole thing about ‘Ants’ was that we felt weird, like we’d crossed the bridge. We were living around all these fucking rich strangers. There’s a school across the road, and you can see the Harbour Bridge out the window.

The song was about, ‘God, I cannot fucking stay in this place. I’d rather fucking kill myself than be in this place’ [laughs]. But at the same time, understanding that the whole I’m alone in paradise lyric is like, no one knows us up here. We can leave the house looking like complete shit. We can leave the house and no one knows who the hell we are.

It’s basically a sea of old people who are chilling—presumably investment bankers or something like that. And it’s, wow, we are kind of alone in the middle of nowhere. It’s sort of nice being able to not see anyone, not having to interact with anyone, and to just be anonymous.

So where you live is the tower you talk about in the song?

J: Yeah, it is.

We can relate because we live on the Gold Coast, it’s laid back but there is a lot of wealth and status, or at least people trying to portray that, here. Everyone always spins out when we tell them Gimmie is based on the Gold Coast.

J: That’s so funny, isn’t it? Like people think that if you move away from the centre of a culture capital, that your art’s going to be damaged or like that you’re different in some way.

We love the weather and being near lots of beautiful nature spots. Brisbane and Byron Bay are an hour each in different directions. We also get to stay out of a lot of scene politics that can happen in bigger music communities. We feel like we’re alone in our own bubble most of the time.

J: Yeah. Living here reduces anxiety. Charlie, especially hates if we go somewhere, and we see someone we know, even if we love them, even if it’s a really good friend of ours, if she’s not prepared for for the social interaction, she’s not keen on it. Here we get to be on a bit of an island. We’re never gonna see someone we know at the local Coles or wherever. When we were living in St Peter’s, everyone who we work with lives there too. We’d go to the Marrickville Woolworths and you’d see three people from bands and your boss—we’re not particularly good at like living in that environment.

Maybe it is because of growing up in Canberra where everyone’s separated so much in different suburbia. We’re not good at being in a city but this feels like we’re in a suburb.

What was the thought behind the album title, Moralizer?

J: I was listening to the lyrics. So much of this shit is so preachy [laughs]. Listening back, there are a lot of lines where I was like, oh, man, I wish I didn’t sound like I had the answers. That was never my intention. But there was so much fucking preachy shit about people who live ‘X’ way and people who live ‘Y’ way, and all this kind of shit. I felt like the title Moraliser was like a funny stab at what the record sounded like—someone standing on a fucking wooden box being, ‘This is how you should do it. This is how you live your life, and I love you. I’m a fucking false prophet.’ [laughs].

I thought it was funny because it was kind of true. It was a moralising record. There’s so much in there, so much critique, judgment and speculation. That was part of the reason I really wanted that last song to have a little upside to it.

In light of the darker take on living on the album, I wanted to ask you, what do you do for fun?

J: What did I do for fun? God, I don’t know. Oh fuck this sounds lame but the funnest thing for me is every Friday the band writes or we record or we practice together, then we’ll go to the pub, it’s become a ritual. Our band is our closest unit of friends.

I don’t have any other hobby I do outside of this. If I ever have free time i’m probably going to do it do music.

Is playing a gig fun for you?

J: Sometimes. It’s not fun before, like the whole day before it’s—okay, here we go. We’re going to go do this again. But really, are we sure we want to do this? [laughs]. This is our life choices? Are we certain about this? And then when you’re doing it, I get on the stage, I’m like, yeah! Fuck yeah! I’m stoked. Afterwards, feels good and a relief too.

Is there a song that’s on the album that has a real significance for you?

J: ’Ants’. It feels like the most whole song where I feel like everything in it is bookmarked really well. Everything is a holistically completed idea. I’m probably biased here because I wrote that song by myself [laughs]. Jack obviously did all the drum parts, and everyone recorded their bits at the time of the final recording. But, I did a demo version of it in 2019 that’s the same structure and mostly the same lyrics.

‘Pills’ maybe, too. It really feels like the first house we moved to in Sydney in St. Peters—with Ewan. That song was very much about time and a place.

Maybe ‘Ain’t Seen Nothing,’ because the big final ending took forever for us to get to. It’s nice having a little verse in there about shacking up and having kids with Charlie.

Awww, that’s really sweet. How is being a part of Negative Gears affected your personal growth?

J: It’s one and the same. Making music has always been a part of personal growth; it’s never been a thing that’s gone away. Seeing the songwriting actualised—seeing a song that I’ve worked on being turned into real life and then reaching completion—gives you a kick from the goal of it. Exploring the depth of how you feel about something is really good for personal growth. Sometimes you just have a feeling about something, but it’s not until you really dig into it that you understand where you stand on that issue. At least, that’s how I feel.

‘Attention To Detail’ is important. I remember I was fucking furious around the time that song got written, and I feel like I got it all out in that one song. Like, ‘Well, yep, I pretty much laid down everything I’m pissed about,’ and it was really cathartic. It was solidifying. It wasn’t just global lethargy; I wasn’t just over the world. I was very specifically pissed about a lot of things [laughs].

For everyone, I’d say it’s been a long journey. We’ve been a band for a pretty long time; all of us have played music since we were young. We all find it a constant ticking eternal thing. That you work on, that gives you a purpose to get through the rest of the week. When someone has a good riff, you’re like, ‘Oh, that’s pretty good!’ It keeps you interested and excited, and it’s something to fucking enjoy when you get off work.

It’s also something to talk about. We have a group band chat where I don’t think there’s been a two- or three-day gap in messages for maybe seven years.

Wow. Is there any particular directions or collaborations you’re interested in exploring in the future?

J: As far as art stuff there’s a bunch of people that I’ve been really interested in seeing if they can do some work for Negative Gears things.

Music stuff, I was literally thinking about this today. Felipe from Rapid Dye, and Toto who I play in Perspex with, and Charlie and Jac did this band that started in the middle of COVID. It was called Shy Violets, sort of a poppy scrappy band. We wrote an album’s with of songs, 10 or 11. And then it all just flamed out. We never did anything with it. We never played a single gig. I’d really like to get that back together in some way, shape or form at some time.

I get to pour most of my creative energy into Negative Gears, which is a blessing and a curse. It is nice to have a break, though.

We haven’t talked about the song ‘Negative Gear’ on the album yet; it’s almost like a theme song for the band, at least that’s what it seemed liked when we saw you play at Nag Nag Nag fest.

J: Yeah, it felt like the theme song on the record. That was kind of the plan. I fucking love that song. I think it’s one of our best. The coolest thing about that song is we all actually wrote it together.

Lyrically, it’s exactly what I described in some of those other songs. Like I mentioned earlier, I was in a spot where I’d been working fucking shit jobs for years, and I really had no idea what the fuck I was doing with my life. The whole thing was kind of flipping it on the band name, being like, ‘Yeah, I’m in a fucking negative gear. I can’t get anything going.’

At the time, I did have a $4000 credit card debt. And I had this big fucking growth in my throat that was freaking me out. That’s the first line of the song: I got a four grand credit card debt and a lump in my throat. It was painfully obvious when I was swallowing because it would make me puke. This weird fucking thing in my throat—I’d drink some beers, and I’d just start throwing up because it was clogging my throat.

Wow.

J: It felt like I’d hit fucking rock bottom. God, my mum’s going to read those lyrics and she’s going to be sad. She’s going to send me some messages. I’m always honest with her.

It sounds like your mum’s an important person in your life.

J: For sure. She’s a very fucking incredibly strong, powerful force of nature. She was a behemoth of a person to grow up with for sure. And definitely still is. She’s a powerhouse. It was the reason I ran away from home when I was 14. But you know… [laughs]. We’ve been all good now for years.

Can you tell us about the song ‘Connect’?

J: It was a bender song. We had the studio in Marrickville at the time. We weren’t the only ones there. Mickey from Den was recording a lot of bands there, and I was recording bands too. Eventually, the rent got too expensive. We turned it into a rehearsal space, which I think lots of the younger bands ended up using.

I’d pretty much tapped out of it. I was sick of managing it, so I passed it to Chris and was like, ‘Dude, I can’t handle this. Do you reckon you could do it?’ And he was like, ‘Fuck yeah,’ and just started getting people in. I think R.M.F.C. was in there, Carnations was in there, and Dionysus was definitely in there. It was this tiny little room in Faversham Street. We built a little studio, chucked all our gear in, and it became a hub.

It was pretty much a song about getting wasted at this place again and again. In the early periods of recording and writing that record—actually more the writing—we spent a lot of time in the studio in Marrickville, having these nights where the sun was fucking rising, and everyone was wasted. It was like, ‘Well, what’s next?’ There was a desperate sense of wanting to reach out to people, that horrible feeling you get at the end of the night where you’re like, ‘Oh, what’s everyone doing?’ or ‘What’s everyone up to?’ And, you’re realising you’re going to be the person chilling on the couch on a random street in Marrickville, sitting outside wasted at 6 o’clock in the morning.

It’s a pretty straightforward song, not much depth, except for one line I throw in… I’m a master of the diss track. That’s the one thing I’ve got down—every song’s got disses in it [laughs]. There’s a diss in the song, something about buying fake iPhones and checking biceps. There was a crew of guys hanging around at that time, and I was like, ‘Oh yeah, these guys are mad!’ I remember telling the guys, ‘Yeah, bro, I gotta get the latest iPhone and start working out so I can fucking hang out with them—it’s gonna be sick.’ [laughs].

Last question, what’s some things that have been making you happy lately?

J: I was stoked when I started realising that the Sydney music scene had regrown and was in a really good spot.

I’m happy in most senses right now. Me and Charlie have a good life. We spend a lot of our time together, we work together and we play in this band and it’s fun.

Outside of listening to, and making, music, I don’t fucking really think about that much. It’s been many years since I wrote the songs for Moraliser— you grow up. Charlie just said those feelings from the record, it’s still lurking, it doesn’t go away [laughs]. I’m very extroverted. I love talking to people. I come across as a super enthusiastic, excitable person, which I totally am in my life. But, Charlie is right in the sense that, I do still tip every couple of weeks, for days on end it goes and that’s when I write the majority of my music. I find that helps when I’m like that. I tip and I lose motivation. I do what everyone does—you fucking hate yourself and you feel like a piece of shit. It’s just part of my way of dealing with it all.

I do think it’s funny, though, for the people that know me well—my close friends—when they hear my lyrics. Because most of the time, I’m like, ‘Hey, it’s so great to see you! Wow, so nice. We haven’t seen each other since Tuesday! It’s gonna be so good to hang out.’ I don’t seem like someone, I guess, who would have that darker side that’s in my lyrics.

But it’s just that I love people, and I love being around people, connecting with them. I love community, and I love building long-term friendships. That’s very different from how I feel inside when I’m alone.

I’m definitely in a much better place than I was five years ago—Christ! [laughs].

Follow: @negativegears. GET Negative Gears’ Moraliser (out on Static Shock/Urge) HERE.