When you walk into Lulu’s, Naarm’s (Melbourne) beloved underground record shop, one of the friendly faces behind the counter is co-founder Alessandro Coco. Along with friends, he helped establish label Cool Death Records too, that’s gifted the world record collection essentials from bands like Low Life, Tyrannamen, Oily Boys, and Orion. A stalwart of Australia’s hardcore punk community, Coco has played in bands Leather Lickers and Erupt, among others. These days, he fronts Romansy, a band channeling the hectic, spirited energy of Zouo, The Clay, Necromantia, Septic Death, and GISM.

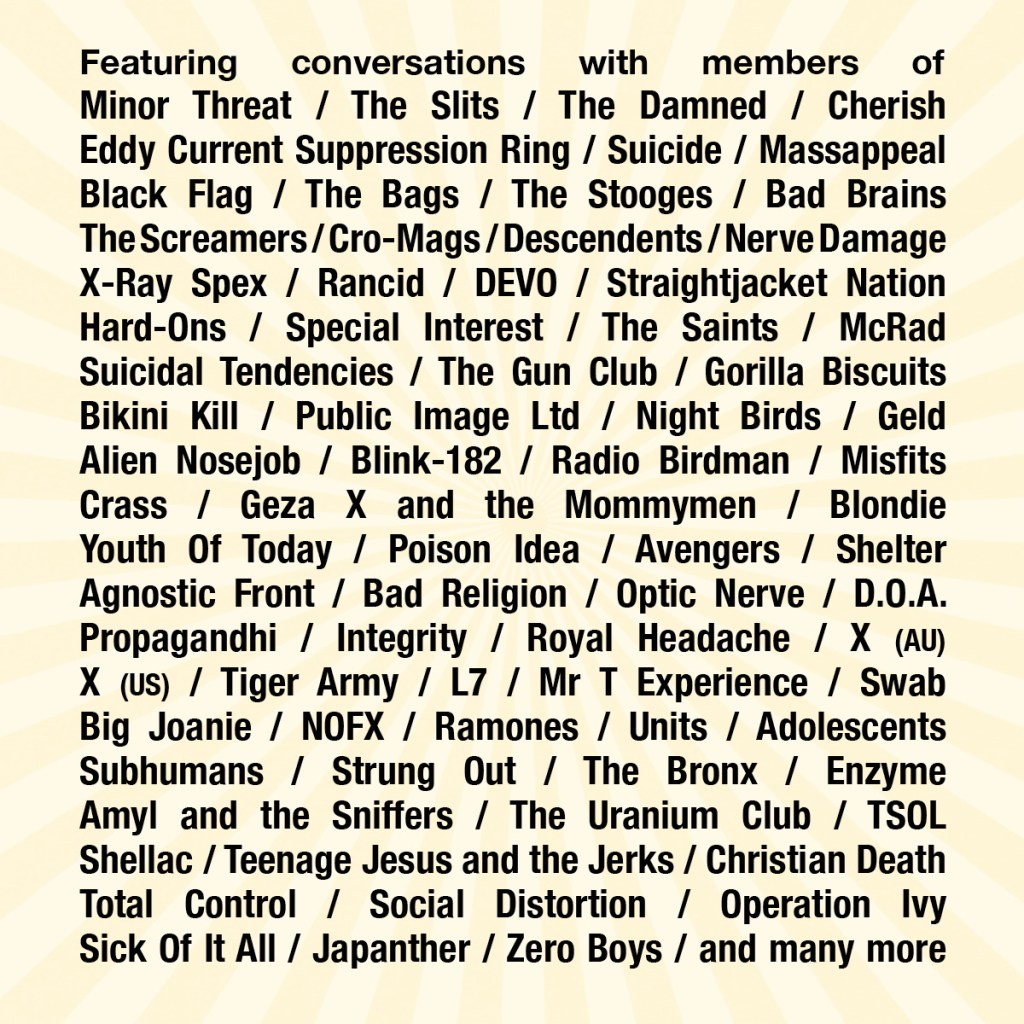

A few years back, I (Bianca) was chatting with Al Montfort (Straightjacket Nation, Sleeper & Snake, UV Race, Terry…) about my punk and hardcore book, Conversations with Punx: A Spiritual Dialogue. Al suggested I reach out to Coco for a conversation—so I did.

What followed was an hours-long discussion that covered self-enlightenment, spirituality, creativity, the DIY ethos, and Coco’s introduction to it all. We talked about the importance of really supporting one another both creatively and personally, navigating struggle and insecurity, and embracing who you are and your own worth. We yarn about the scene and its dynamics, as well as idolisation. Coco also spoke about messing up, owning it, and growing from those experiences.

The initial manuscript for my book was over a quarter of a million words. To bring it to a publishable length, I had to cut it in half, which meant not every full conversation made it in. A few days ago, Lulu’s announced they would be closing their High Street shop. Lulu’s has spent nine and a half years of hard work, creating a hub that felt like a second home for many of us in search of great underground music, connection, and community. Reflecting on Lulu’s reminded me of the chat with Coco—and the timeless insights we shared. Which Gimmie now shares with you.

Al informed me that you’re always talking about philosophical, deeper, spiritual kinds of stuff. So I thought I’d reach out for this chat for my book.

COCO: Yeah, I definitely am. I’m surprised that more people don’t talk about it, but I get it. Everyone has those thoughts and ideas, but they tend to keep it personal. Sometimes it’s something people think, or feel but don’t really focus on. They might not dedicate hours in the day, week, month, or year to hone in on it. It’s just there, part of who they are, which is cool as well. Star signs are back in a big way, which is kind of cute, but that’s where it usually stops with a lot of people [laughs].

It’s obviously something that you focus on?

COCO: For sure. I do my own thing with it. I don’t attend regular church meetings or group gatherings. It’s something I focus on in my own time, putting energy into it. You can find powerful, positive, and profound results from doing that. It suits me.

Once you’re aware of that kind of power and presence, you can’t ignore it. It’s right in front of you, you just have to meet it halfway.

When did you first became aware of it?

COCO: I couldn’t pinpoint it exactly. I grew up attending Catholic schools, and that was fine, but it always felt strange to me. You’re presenting something profound and serious—something meant for adults—to children who can’t fully grasp it. Kids aren’t taught philosophy in primary school, and rarely in high school, yet religion is essentially a philosophy. It’s no surprise they don’t understand it.

When you grow up with that, you either follow along and risk developing a warped perspective, misunderstanding it, and running in the wrong direction with it, or you reject it altogether. That rejection is understandable but often comes with throwing out the good with the bad. There are powerful, useful aspects to it, but they can get overshadowed by the parts that seem cruel, wicked, or nonsensical. This can lead people to turn their backs on it.

As for me, I don’t know exactly how I came back to it. I’ve always been fairly optimistic and positive when I can be. Maybe it started with playing music and spending time with friends. A lot of us got into heavy metal around the same time, and that genre is steeped in spiritual symbolism. You start noticing it, paying attention, and digging deeper into what those symbols mean.

Symbols are fascinating. They condense grand ideas into something small and simple, like a logo anyone could draw. Exploring those symbols led me to rediscover some ideas and reconnect with them. As an adult, with more maturity and life experience, you can approach those concepts differently. You start deciding what they mean for yourself. Once you’re on that path, it’s easy to keep going and noticing it everywhere.

Absolutely. What is spirituality to you?

COCO: At its core, I would say it’s our way of experiencing our environment and identifying ourselves within it. What does that mean? Well, it’s philosophy. That might be an oversimplification, but I think it holds true.

For example, I might have a buddy who doesn’t consider himself spiritual. Yet, if he goes hiking or visits the beach, he tells me how connected and wonderful he feels. He mentions how the everyday things that seem so important drift away, leaving him with a new sense of connectedness and a different way of experiencing and being part of his environment.

To me, that is spirituality. He might not identify as a spiritual person, but that experience—feeling in tune with the world—is exactly what spirituality is about.

Totally. I get that from nature, I get that from listening to music, or creating something too.

COCO: It’s a weird kind of connectedness. It’s about relating to and experiencing life, but not in a social or political way, or in all the other ways we tend to focus on. It’s just you and the world—whatever that is. That’s often what it comes down to. It leads to other things, sure, but at its core, it’s just you in that moment.

Take music, for example. Black Sabbath is my favourite band. There are certain moments—like after a few beers, when the ‘Wheels of Confusion’ riff in the middle hits—that completely takes me away. That connection, that rush of vital energy and passion, what it does to your body and mind—it’s ecstatic. It’s an experience that feels almost otherworldly.

And that happens with all kinds of music. It’s that feeling, that sense of being taken out of yourself and into something bigger. Is that spiritual? I don’t know. Some people might not call it that. Maybe if you’re just bopping along to a pop tune, it doesn’t feel the same. But everyone has their own way of looking at these things.

For me, it’s huge. It’s a big part of how I see spirituality—not putting it all into neat little boxes, but recognising it in moments like these. It’s also about being present in mind and body, living fully in the moment. That idea comes up a lot in Eastern philosophy and spirituality: being present, not caught in thoughts, just experiencing and being.

You can get that from listening to music, from live performances, even from watching sports. Everything else drifts away, and it’s just you and the experience—the present moment. Nothing else exists in your head or your being at that time. It’s pure, and it’s wonderful.

Absolutely. Are there any other practices or rituals you have?

COCO: I don’t meditate in the traditional sense—not the sitting down with eyes closed, yoga-style meditation. Instead, I try to get in touch with things in my own way. I’ll light incense, light candles, or pull out the tarot deck. Sometimes I pray, just to connect with what feels like it’s always there, everywhere, all the time. It’s about getting in tune with it.

Whether it’s positive thinking, willing something into existence, or something else entirely, it’s a complicated idea to explain. I don’t follow a strict practice, but I definitely have my own ways of engaging with the universe—and sometimes even the unseen universe.

Have you looked into any specific philosophies?

COCO: I mostly find myself drawn to Western esoteric traditions, whether that’s Kabbalah, Christian mysticism, or other forms of Western magic. Many of these traditions also look to the East for inspiration. While I don’t spend as much time exploring Eastern ideas or philosophies, I do visit them occasionally. I think there’s truth in all of it, and something valuable in every tradition for everyone.

I can’t say any one path is greater or better than another—it depends on how you approach and understand it. For me, Kabbalah feels especially useful and powerful. I probably came to Kabbalah through reading [Aleister] Crowley. It resonates with the way my mind works and how I think about things. Similarly, Christian mysticism makes sense to me, likely because of my Catholic school upbringing. I’m already familiar with the imagery, symbols, language, and framework, so it feels accessible.

That familiarity allows me to focus on those traditions without the overwhelming task of learning something entirely new—like the canon of all Hindu gods, for example. That said, I do enjoy exploring other traditions when the opportunity arises. You can use whatever word you want for it, like, religion, philosophy, magic, spirituality, they all lead to the same place. Obviously, there’s different ways of practicing it or experiencing it, but hey’re all part of the same tree.

Do you think your interest in these things stems from trying to understand life or yourself better?

COCO: Yeah—it’s about seeking truth. It’s about seeking experience, seeking understanding. Sometimes, it’s about finding another way—a useful way—of looking at the world, another lens that can open your mind.

I used to smoke a lot of pot. I don’t anymore, but at that time, I think anyone who first forms a relationship with that—or with psychedelics—definitely experiences a kind of opening of the mind. It starts you looking at things differently and even experiencing things outside the box. Once that door opens, things can just keep opening.

It’s not like psychedelics are the only gateway to that kind of exploration, but I think, for a lot of people, they are one of them.

Where did you grow up?

COCO: When I was a kid, I lived in the western suburbs of Melbourne. During high school, I moved out to the country in Victoria and stayed there for 10 years. A few years ago, I moved back to Melbourne because everything I do and participate in is based here. There’s not much of that up in Ballarat, where I lived, so had to come back to Melbourne to be part of things the way I wanted to.

How did you first get into music?

COCO: When I was younger, I got into The Offspring, Nirvana—cool stuff like that. Some buddies in high school were into similar punky music, and I ended up getting a Punk-O-Rama compilation. Not long after, I got into the whole Australian metalcore scene, which quickly led me to Australian hardcore and melodic hardcore—the stuff that was happening about 15 or 20 years ago. From there, I dove into more classic punk and eventually got into the underground scene.

Both my parents are big fans of music, but they didn’t listen to punk or anything like that. Over time, though, I’ve come around to their tastes. My dad schooled me on a lot of classic and important blues, and my mum actually got into punk after I did. She loves it now, along with hip hop—she just vibes with that kind of stuff.

So, yeah, there was music in the house, but I didn’t really find my own music until punk came along. Something about it just made sense—the attitude, the volume, the aggression, the appearance. It’s the kind of thing that captures a young mind full of energy but unsure where to direct it. There’s also that rebellion, which is so easy to identify with, especially if you’ve never really had a way to express it before. You see it, and you think, Oh, yeah. That’s it.

What was your first introduction to DIY?

COCO: When I was getting into metalcore—it called itself hardcore at the time—I started to realise that these bands were actually touring and playing at venues I could go to. For all the flaws in that scene, they did a lot of all-ages shows, which was great for younger people to access. That made it feel like something real and achievable.

It wasn’t happening in my own backyard, not where I was from, but it was close enough to get to. Tickets were like 15, 20, maybe 30 bucks, and you could actually go and experience it. At first, I thought of it as a concert, but then I realised it wasn’t this big, untouchable event—it was just a gig. And at those gigs, everyone had their band T-shirts, their merch, and it all felt alive. You’d see one gig, and then there’d be another, and you’d just go further down the rabbit hole.

I started to see that this scene was happening in the present—it existed right here and now. In Melbourne, we were lucky because there was so much going on. One thing led to another, and you’d discover these whole communities of people doing it themselves.

Missing Link Records in Melbourne was super important for me. They were really supportive of younger people like me. I’d go in, buy a CD, ask questions, and they’d help order stuff in or give recommendations. Even at the gigs, there’d be distro tables with records and CDs for sale. You’d chat with someone there, and they’d put you onto new bands or scenes.

I remember this one guy who ran a label. Looking back, it wasn’t the coolest label, but at the time, he was so enthusiastic. I laughed when he handed me something and said, ‘Dude, you’ll love this.’ I was grabbing Jaws’ new thing on Common Bond Records, and he’s like, ‘Oh man, if you like that, check out Government Warning.’

I bought the CD No Moderation, and that just flipped everything for me. I was like, man, this is unreal. And yeah, it’s just about having your eyes opened to the fact that it’s all around you—you just have to notice it, or be introduced to it, and then experience it and break into it yourself.

The local scene came from local shows. The DIY thing? You just kind of follow the rabbit hole, chat to different people, explore different things, and then you realise it’s all there.

And now you get to do that—recommend new stuff to people who come into Lulu’s! I read in Billiam from Disco Junk’s zine Magnetic Visions that he mentioned how, when he went into your store, Lulu’s, it was the first place where he actually felt like he kind of belonged. He said he didn’t feel like he was inconveniencing anyone, and he could actually have a chat with people. I could relate to that. Growing up, many people behind the counter at my local record stores were really pretentious and condescending but then there were a couple of cool dudes that would take the time to talk to me and suggest stuff, and that made all the difference. It’s like, not everyone can know everything.

COCO: Yeah. That’s my favourite part of Lulu’s: being able to chat with people, connect with them on a personal or musical level, share things we think are cool, and point people in a direction—like, ‘Oh, you like this? Maybe you’ll like this. Check this out! Have you heard of this?’ Then encourage them to do what they’re doing.

Billy was young doing his own music, and I was like, whatever you do, buddy, bring in your tape, bring in whatever you make, to encourage and support that. I was lucky enough, when I was younger, to have people be really friendly and supportive of me. I always thought it was important to pay that back. I was shown kindness and support, and I thought, ‘Yeah, I absolutely want to do that for anyone else I get the opportunity to help down the line.’ Thankfully, I’ve been lucky enough to be in a position where I can do that. DIY is a hell of a thing.You get to learn a lot of lessons your own way.

If you want to do a band—do it! Nothing’s gonna stop you, no one’s gonna stop you. Make your tape; the first tapes we did we dubbed by hand. I spray-painted the covers. You just have to give it a shot. Put your effort into it: use your brain, your heart, your passion— it can pay off for you.

Early on, that was super valuable to learn; it’s influenced the way the following years of my life have gone. If I wanna do something, chances are I can do it. I’ll always encourage others to be themselves and do their thing. It’s easy not to do something. When you do, though, the satisfaction, the joy of people digging it too, appreciating it, and caring about it, is huge!

Encouraging people to be themselves is something that’s really important. More people need to know that it’s okay to be yourself—to ask: What do you like? What don’t you like? What would you enjoy without the influence of others?—and to know that they are enough already. A lot of people seem to think they need fixing but if you look around at the world, what we get bombarded with, messages we’re sent, and systems that are in place, it’s no wonder you feel how you do.

I know from talking to a lot of creatives over the years (and through my own experiences) that many of us tend to be really insecure. We compare themselves to others, which fuels feelings of self-doubt, not being good enough, low self-worth, fears of not having what someone else has, and can lead to anxiety. Over time, that can start to really get you down.

COCO: Totally. A lot of people would be lying if they said they didn’t compare themselves to others. And we do—we look to friends, family, community, media. We idolise certain people from the past or present, or whatever it is. That’s all well and good; it can also lead you on a good path. A lot of those influences can be good and healthy. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.

But at the end of the day, the lesson to be learned is to be yourself, be proud of that, and do your thing. Do it to the best of your ability—do things your way. It can work, and it can be really satisfying. It’s so nice to break free of expectations you don’t believe in or value. Then you can just go on and do your own thing.

Even with all the spiritual stuff—whatever it is—it doesn’t mean you have to be a goody two-shoes, or a badass, or anything else. Break down all the bullshit that doesn’t matter to you. Use your head, listen to your heart, and let them guide you. Find your own way in the world. Being yourself, doing your thing, and keeping it real—that’s the only way to go.

We’ve all experienced the opposite of that, you know? I think probably everyone who’s made it through their teens knows what it’s like to not be like everyone else—not be as good at something, not be as good-looking, not have the cool clothes, or whatever it is you’re valuing. Not be good at sports, or whatever—blah, blah, blah.

Even me—I’m not the best musician, I know. I’m not the best artist, or whatever. But I know what I like, and I know how to do what I like. Doing that has provided me with so much satisfaction. And it’s been great too, because certain things I’ve gone on to do have had a positive flow-on effect. If I hadn’t done them, maybe someone else wouldn’t have heard something or experienced something at all.

That snowball effect, that ripple effect—it’s insane how the things anyone does can touch another person for the better. That’s why you have to be yourself, because if you don’t do it, no one else will. The world would be a fucking dull, miserable place without people going out and being themselves, almost no matter what the cost.

It’s given us some of the best things we’ll ever know—some of the best art, ideas, thoughts, and all those things we care about. All the cool stuff.

What was your first band?

COCO: An awful band in high school that I played bass in for a bit [laughs].

When I first started doing my own thing—writing music, doing it with my friends, and making it the way we wanted—it really felt like mine. That was, Kicked In, which we started in Ballarat with Tom, who does Cool Death with me and Lulu’s as well.

That band was around for a little while, but then our guitarist and singer decided they wanted to do other things and didn’t want to continue with it. We made a few cool tapes, though. When we got a new guitarist and singer, we decided to change the name, and that’s what became Gutter Gods.

Gutter Gods ended a few years ago—toward the end of summer 2015–16. We split up, which was a bummer at the time. But you know, it led us all into other things. The work we did with that band really opened up the world for us. It gave us confidence, and we got our kicks with it.

You make friends, you make connections, you build confidence. It made us all really comfortable with starting other bands and putting that same passion from Gutter Gods into new projects.

What do you get from playing music?

COCO: One of my favourite things—it might sound cheesy—is just jamming. A good jam with your friends is like nothing else. Whether you’re making something up on the spot and it all just flows out of you, or someone’s written a song and you come together to play it for the first couple of times, it’s really like nothing else. I don’t know why or what it is, but it’s the joy of creation—seeing and feeling something while you’re hearing it being made real.

It starts coming out of the amps, the drums kick in, vocals hit the mic, and it all has this vital energy. You’re like, Wow, that started off as nothing. It’s basically making something out of nothing, and when that happens, it’s huge.

Playing shows, though, I have a weird relationship with. Sometimes I don’t love it; other times, it’s brilliant. It’s funny how often you think a set was awful or you played badly, and then people come up to you later saying it was excellent and they loved it. Other times, you think you’ve absolutely killed it, only to find out they couldn’t hear the guitar the whole time. It’s like, I thought we smashed it, but everyone thought it died because of the sound or the crowd, or whatever.

It’s really hard to put my finger on what I love about playing or making music. It’s like I have an impulse to do it—it just has to be done.

I was watching this documentary on the blues recently, and there was this line someone said that really resonated with me. I can’t recall it off the top of my head now, but I sent it to a friend, and they said, Yeah, that’s exactly how I feel too. It was something about the blues being not for anyone else—not for anything—it’s just you. It’s like yelling into the universe: Here I am. Here’s this feeling, this atmosphere, this whatever. It’s just a way of creating something that’s in some way a part of you. And then it becomes this sound, this artwork, this song—this thing that is its own entity.

Have you read The Plague by Camus’? There’s that guy in the apartment trying to write the perfect book. He’s obsessing over writing the perfect book. Throughout the whole story, he’s sort of like a Kramer—just crashing in, chatting, getting in the way, and showing this one line he’s been working on. He keeps trying to perfect that single line and never gets past it.

It’s funny to think about because it’s kind of sweet. When you’re making a song or whatever it is, it’s not like your last will and testament. You can’t sum up everything you are, think, feel, or believe in one song, one lyric, one riff, or one painting. So, when you’re creating, all these things are just little parts of you that get to have a life of their own.

With music especially, it’s often a collaborative thing. Every member of the band gets to put a piece of themselves into that song or sound, and it happens over and over again. It’s interesting when it comes to expressing yourself, though. That’s such a big part of it, but you can be expressing so many different parts of yourself.

Take punk, for example—super aggressive, super in-your-face. But that doesn’t mean you don’t have another outlet where you express something completely different. It’s all part of expression.

Even then, like, you know how when you listen to a great song, you feel that connection? Sometimes you find that with your own work, too, and it’s really satisfying—hearing or performing your own song. It’s a way of speaking, particularly with instruments, without using words. You create this thing—an atmosphere, an energy—that becomes intangible but still real for you and for anyone who comes into contact with it.

Sometimes, even when you look back at stuff you’ve created, the meaning of it can change from when you made it—or even when you play it live. It can keep evolving long after the initial spark of it coming into being.

COCO: I totally agree. Even bands might have a slow version of a song they play live, or some track you like live. Like, oh, what? They did an acoustic version of this concert in 1976, and you check it out—it’s like, whoa, that just carries a totally different feeling, or a more powerful version of the original feeling. The song you write, the words you write—particularly with words—you can look back at things later, and you’re right, that meaning, can evolve.

That’s the other part that is on a spiritual tip. Sometimes when we’re creating things, it feels like it’s not necessarily yours. You really are just channeling something else, and you’re there as a conduit for that. In doing so, you often put your own thing on it because it’s coming out of you, but it’s expressing some idea. Whether that idea is always going to be universal—whether it’s archetypal or whatever—it doesn’t really matter. Whether it’s coming from you or somewhere else, it’s as real as anything else is.

Yeah. When I interviewed Randy from Massappeal for the book, he was telling me that when they had practices, some of those were even better than his favourite live shows they played. He shared with me the moment during a practice where he had a massive spiritual epiphany!

COCO: 100%, I stand by it that, like, the best music I’ve ever played has been in the practice room. Some of those experiences we’ve had in the practice room—where the vibes are right, the atmosphere is there, and everything just happens—whether it’s, you know, a bit floppy or whether it’s tight or whatever. Yeah, easily the best music, the best sound I’ve ever made, has been in this practice room, and I don’t know what that is. I don’t know if it’s just, you know, being able to cultivate that vibe with yourself and the people you’re playing with, or if it’s just like, you know, a probability thing. It’s like, well, you probably practice more than you play live, so the odds are you’ll do the best version of a song, you know, one in a hundred times, and that happens to be in the practice room. I totally, totally vibe with what Randy said.

It’s a pretty special thing, too, that you only share with these people who are in that same frame. A good jam is better than good sex. At the height of it, it’s easily one of the best things I’ve ever experienced—having a good run through a song or a set, or making something up on the spot, just creating without words. That’s another reason why I’d encourage anyone who ever thinks about picking up an instrument, playing music, or starting a band—whatever it is—I’m always like, do it. You have no idea how good it can be until you do it. Anyone who ever mentions it, I encourage them right to the ends of the earth.

Same! At Gimmie we’re definitely cheerleaders for humans creating art!

COCO: I totally get that feeling—you can only describe it so much, but there’s a whole other layer to the experience that you can’t pass on. It’s like, you really have to be in it, feel it, and discover it for yourself. That’s what makes it so special, and it’s hard to convey unless someone’s really there.

It’s amazing how much music can shape people’s experiences, emotions, and connections. It’s its own language that transcends words, and I love helping others explore and articulate their musical thoughts.

Do you play in a band?

I had bands when I was younger, I’ve made music just for myself my whole life. Jhonny and I have a little project we’re working on just because we love making stuff together, it’s fun. Jhonny has taught me so much about creativity, and helped me overcome self-doubt and to learn to trust myself, and to play and explore. He has some of the coolest and most beautiful ideas about creativity. I feel so lucky to spend every day with him. I wish more people knew just how brilliant he is.

COCO: That’s cool! Yeah, I totally get what you’re saying. Certain songs I write, when I pick up my guitar, a lot of the time, I’ve got songs from years ago. I don’t know if I’m ever going to use them or whatever, but they’re there, and I enjoyed writing them. Just being there with your guitar or your amp or whatever it is—or sitting on the drum kit and playing the fucking D-beat for as long as you can!

I remember having this taxi driver once. I told him I was a drummer, and he’s like, ‘Oh man, that’s really cool. There’s just something so human and so real about drumming.’ I reckon at the end of the world, there’s this guy sitting on a mountain playing 4/4. I’m like, ‘Dude, I totally believe that.’ It’s like the strangest, silliest, most poetic thing. Once he said it, I’m like, ‘That’s it, man.’ [laughs].

There’s just something about music. It’s profound because it doesn’t make sense to other animals. It barely makes sense to us. The reason we have our own connections with it, a lot of it, is in us and inherited—whether it’s culturally or biologically. It can easily get mystical, and it’s really hard to understand why it makes us feel the way it does, but you know it does. That’s why you pursue it, I guess. Sometimes you just have to fucking say, ‘See you later’ to that logic and rationale and whatever, and try to understand things or break things apart. That reductionist thing—it’s like, fuck, it’s real. Go for it. I’m going to be in that realness, because it makes me feel better than almost anything.

Absolutely!

COCO: I’ve had a few epiphany moments. Some have been without so much thought or words. It’s this experience, like I said, with encouraging people to play music or do whatever. It’s often said of any spiritual pursuit—more enlightenment in the East—I can’t give that to you. Like, even if I had enlightenment or I had the meaning of life or I had this understanding, if you ask me the question, the answer I give you isn’t then going to convey that knowledge or that same understanding to you. You have to just experience it for yourself.

With life-changing moments, that’s a really similar thing in that it might be impossible to convey. But some of how it happens is often this sense of a sort of ecstasy and interconnectedness and maybe synchronicity. I mean, the good life-changing moments, not the absolutely awful ones that shatter your world. But again, they’re actually quite fucking similar. They just feel a lot worse, I guess.

But it feels like everything has conspired to meet in this moment, and it just happens, and it takes you away from everything else. You feel it in your body, in your mind. The beautiful ones, they often follow a lot of similar patterns. Often things happen on a whim, maybe slightly unplanned. They’re always unexpected. There’s not necessarily ingredients or a mathematical formula that you can put in and the result is a big life-changing moment. These things happen, and one leads to another, and all of a sudden, you find yourself in this state of sort of awe. You feel fulfilled and completed in that moment, and perfect. It’s like you couldn’t be any better. You couldn’t be any more perfect. Things are exactly as they’re meant to be, and it’s that weird, sublime feeling that culminates.

I know exactly what you’re talking about, I’ve been getting that feeling every step of the way making this book, Conversations with Punx, that we’re chatting for. Most of its journey has been synchronistic, and one path leads to the next. It’s all been intuitive. Each conversation I’ve had for it, I’ve walked away with something that’s helped my own life be better.

COCO: That’s one of the rewards for following your own path and going on your journey and doing that thing that is you—being real to you and being nothing but yourself. You totally get that. It’s you and the universe interacting. It’s hard to explain. It’s like, right now, if I look out my window and I saw a fucking dove fly past carrying a rose in its beak, I’d be like, ‘Wow, that was…’ and I tried to explain it, and it’s like, well, what? It was just a bird, you know? But it was more to me. It’s really hard to convey those things to someone else. But when you experience it, it’s like, you realise this couldn’t have happened unless I took that step that I took and the one I decided to take before that. If you take that step, something else happens and meets you. That journey—is the dance of life that people talk about. It’s good to be an active participant in that.

You have to put a trust in yourself and back yourself. I had to do that with this book. Especially in the beginning, I’d tell my friends what I was working on and a lot of them would be like, ‘Punk and spirituality? Religion! Fuck that.’ They totally did not get it.

COCO: Yeah, there can be all these outside things when we do stuff that will try to discourage you or not get what you’re doing. You’re definitely not alone in that. But then you keep going, you do you, and you meet people who do get it. It helps give you this affirmation or indication that what you’re doing is what you are meant to be doing. That’s a wonderful feeling.

Yeah, absolutely. If I didn’t keep going, we wouldn’t have had this conversation, I wouldn’t have got to have such an epic chat with Dan Stewart (Straightjacket Nation/UV Race/Total Control) last week, and I wouldn’t have had a the beautiful chat I had with HR (Bad Brains) a few weeks ago. Or anyone else in the book. I still can’t believe I get to make this book! It’s wild.

COCO: I’m dying to read them!

I can’t wait to share them with everyone. HR was really lovely. Talking to him can be a bit of a roller coaster. I’ve spoken to him a few times over the years. It went a lot better than my chat with Dr Know from Bad Brains, who was condescending and difficult and he kept calling me ‘baby girl.’

COCO: It’s a weird one when you realise that with some people, their creation and who they are, they’re different things. That’s what they say about meeting your heroes sometimes. Maybe people need to not expect the wrong things of people. They are just people. They might be dicks but they might have made something that I may find inspiring and powerful. But if I had a beer with them I might not get along with them but that’s okay too.

Of course, I don’t always agree with what people do but I like their art. I don’t vibe with people being condescending, though. To me, being called ‘baby girl’ is demeaning, I’m not a fucking child. That brings up the conversation of separating artists from their art. Why sometimes we can do that and sometimes we can’t.

COCO: Some people, unfortunately, are just a bit horrible to women or outsiders or whatever they might perceive that to be, and that’s a shame that, I guess, we live with. People are fucking complicated.

I’m glad that HR was cool. Bad Brains, to me, they’re the greatest hardcore punk band of all time. I still, after all the years I’ve listened to stuff and gotten into the best, most obscure bands—whenever that conversation comes up, like the top five bands—it’s easily Bad Brains. They give me everything I want from this music. There’s something really otherworldly and powerful about what their music did.

They’ve had every type of punk and hardcore in their songs. Their performance was amazing. The way it can make you feel—they had you in the palm of their hands. They often said they were channeling stuff. For HR to be able to do those fucking backflips at the end of a song and land on this feet on he last beat—what the fuck, man? That’s crazy. The dude’s not a gymnast. He’s not an athlete. He’s not going to the Olympics. It was this other energy going on, tapping into it and being a part of it.

And that’s why they’re so enduring. We even talked about some of the controversies, like the song ‘Don’t Blow Bubbles’ being anti-gay. He said that at the time it was him following his religion; Rastafarians are known to be homophobic. He said that he feels very differently about it now and would never want to do or say something that harms someone. I think that’s a good example of someone growing and evolving. Often in the world, people don’t give others that room to learn and change and grow, they cancel them rather than have constructive conversations. Like, rather than hate on Bad Brains for it, I asked them about it.

COCO: Totally. We’ve all said and done bad things in the past, and unfortunately, a lot of us will say and do bad things in the future. But when you can come around, realise those things were mistakes, and understand on a deeper level why they were hurtful, it’s part of growing, being yourself, and experiencing the world around you.

Bad Brains were from America—a weird place. D.C., New York, and whatever were weird places at the time. A lot of stuff, like homophobia, was unfortunately really normalise. These strange societal norms can culminate in bad behaviour that maybe wouldn’t happen now, with the benefit of hindsight, growth, and progression. Through conversations and new perspectives, we kind of go, ‘Oh yeah, I don’t say that word anymore. I don’t treat people different from me that way anymore because I realise it’s fucked up.’

That’s really important, especially with all the cancel culture nowadays. Education and thoughtful conversations with people can change lives, open them up to new perspectives, and hopefully, ultimately help make things better for everyone.

COCO: It all comes down to whatever your thoughts and beliefs are. The things that dictate your actions have to come down to effectiveness. If you’re going to shun someone for a certain thing—a word, an action, or whatever—maybe that’s the best way to go about it. But I think, in a lot of cases, it’s not actually the most effective way of dealing with the issue or the person.

Sometimes you need to be more patient with them. I also understand that some people have run out of patience. For example, someone might say, ‘How many men do I have to explain misogyny to? I’m sick of it.’ And that’s fair. In those cases, you might hope there’s someone else who can have that patience and show the person another path. We all draw our own lines in our own places.

That said, there are certain scenarios where I might feel justified in fighting someone or being physical with them. Admittedly, those would be pretty extreme situations—hypotheticals, really. I don’t think it’s the first way to solve problems. But sometimes, it can feel like the quickest and easiest way to get through to someone. For example, if the only way you think they’ll understand is if you hit them, well, not everyone will agree with that approach. It’s a weird one, you know?

People have so many sides to their personalities. It’s not always about being the nicest or the most morally upright. If you look at archetypes throughout human history, war is one of them. Whether it’s a war of thoughts, words, or actions, battles happen everywhere, and we participate in them. Confrontation can take different forms, and that’s okay too. You don’t have to be a pacifist.

Pacifism can sometimes lead to situations where people don’t speak up. I’m not saying violence is the answer, but we’ve all been in situations where someone says something bigoted, and we bite our tongues or walk away. Later, we feel terrible for not saying anything. You end up thinking, ‘I wish I said something’ or, ‘Why didn’t I stand up for what I believe?’

If you’re in a position to do so, you might ask yourself: did I let them know I don’t agree? Did you say, ‘Hey, that’s not cool’? I get that some people might not feel safe speaking up because it could jeopardise their job, physical safety, or social wellbeing. But sometimes, that fire—that fiery nature—exists for a reason.

If you hear something and feel the need to stand up, then stand up. Use your words first. But if people react badly, it’s a different story. I’m lucky enough to be healthy, male, and confident in my body. I’m not afraid of someone trying to punch or fight me. But I know plenty of people who don’t feel that way, and I understand why they might avoid confrontation.

Still, I think it’s important for everyone to find a way to feel powerful and confident in themselves—so they can say and do what they need to without fear. Everyone deserves to be able to stand their ground when and where it matters.

What’s some things that you believe in? What do you value?

COCO: That’s a big question. Like we’ve touched on, I value being yourself. I value respecting other people and their right and ability to be themselves, without harming others.

I personally believe in connection. To ourselves, our heads and hearts and spirit and imagination, to each other, to the world around us and inside us, seen and unseen.

I feel that we are full of potentiality, but I recognise just how much we can be stifled at seemingly any turn. Life will be a struggle for everyone and everything at some point, and every living thing finds its own way of facing this struggle. It perhaps is fitting to include something which I wrote on the anniversary of the death of a musician near and dear to my heart.

In recent times a lot of us are coming face to face with ourselves; with our bodily health, our mental health, our wellbeing and what that truly means. We are confronting our own framework for caring for ourselves and each other; our existence, our mortality and what that means. I am reminded that each and every one of us have something wonderful to offer and many truly rich things to experience. I am reminded, and would like to remind you, that by pursuing our ambitions we can also reach and impact others in a way which is meaningful, mighty, magical and immortal.

We have to look out for each other and take care of each other and support each other.

The societies and cultures we find ourselves in say that they value people becoming and being their best selves but instead their collective actions show us, and what we perhaps sadly see more commonly, this ruling class sanctioned sort of life which values a certain order and commodity structure which really does not have everybody’s best interest at its heart. I imagine it’s been this way for a long time. I think this is where we find people gravitating towards an underground culture or a community which people can be a part of where in its best or ideal instances will dictate its own values and nurture people in its own way. Whether or not it’s perfect, at the very least it’s an alternative, and it’s often the lesser of many evils for a lot of us; a step in our own direction.

I have respect for the natural world—all the critters and creatures out there in the land, sea, and air, and the plants. We just get in touch with who we are and what’s real in the world—that’s really important. Stay up all night, watch the sun go down, and then watch it rise again. There are all these things that help us find our own values through our experiences. We have to work these things out for ourselves.

Like any of us, it’s the things that lead to joy and fulfilment. I’m not talking about cheap joy or fake things. There’s a lot of weak, weak pleasures out there—stuff that’s just not worthwhile. Again, we will draw our own lines there. I’m talking about a healthy way of leading to satisfaction and joy, and bringing love.

A lot of the time, we circle back to when we were angry about something, or when we feel the need to fight, shout, or rebel over something. That often comes from a place of love too. If you hate something, it’s because you love something, whatever that is. It’s just about working out why that is and understanding it. And guiding yourself from there. Sometimes you might get angry over something, and it might be like, ‘Oh man, that’s because I love my comfort, and now something’s going to happen and inconvenience me.’ And now I’m really angry. It’s like, well, shit, man, that’s not really worthwhile, is it?

Anything else you’d like to share?

COCO: We all should be valued, but those weird lines about where you are, what you do, and whether that’s considered valuable or not in scenes really bum me out sometimes. Some people that are known and popular get treated better than others, especially in underground music. It bothers me that some people get a pass, and all this adoration—or whatever the fuck it is that people suck up to—while someone else, who’s a genuinely nice person doing cool stuff, doesn’t get noticed or respected the same way. They don’t get treated equally, and that really does bother me.

That bothers me too. It’s weird that even in underground music communities there’s a hierarchy and it’s about popularity. And I’ve never bought into liking something because everyone else does, often it’s not the most popular things that are the raddest. Doing Gimmie we know so many talented people that consistently put out great, great work but it largely goes under appreciated. If you were to look at mainstream music publications or even indie blogs etc. in this country as a guide of what is happening in Australian music, you’d think it was fucking lame. But we know there’s a whole underground making Australia one of THE best places in the world for music right now.

COCO: Totally! The world is a richer place because of people like you guys doing your thing and sharing stories with ideas where artists are equal, and through your words promoting meaningful, worthwhile things to the world. We’re all better off because of that. Gimmie adds so much value to our community and the world. I totally believe in that.

LISTEN/BUY Romansy here. FIND/EXPLORE Lulu’s here and Cool Death Records here.

Fun facts: Around the time of our chat, Coco was listening to MMA and philosophy podcasts, a lot of obscure black and death metal (including the latest StarGazer (SA) LP, Psychic Secretions), some country blues, and Pop Smoke and Stormzy. At the gym, he was rolling with the (then-new) EXEK and Low Life records and thought the new Romero LP was “smashing.” He’d recently picked up the Sick Things 7”, which he enthused was “a total ripper.”