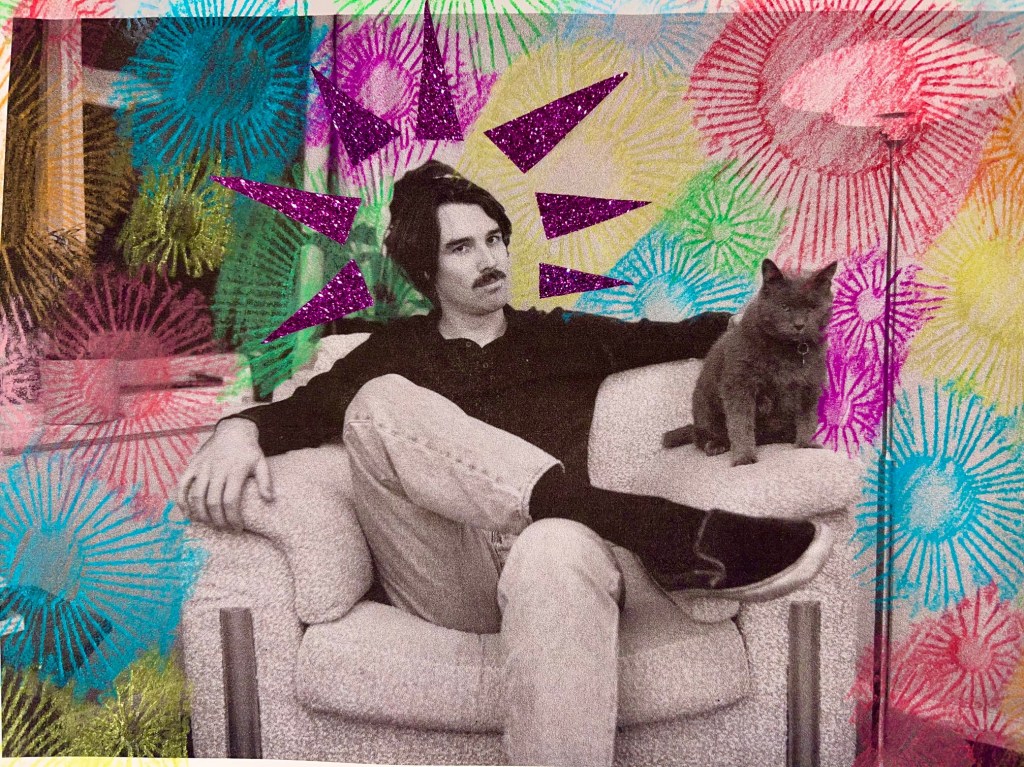

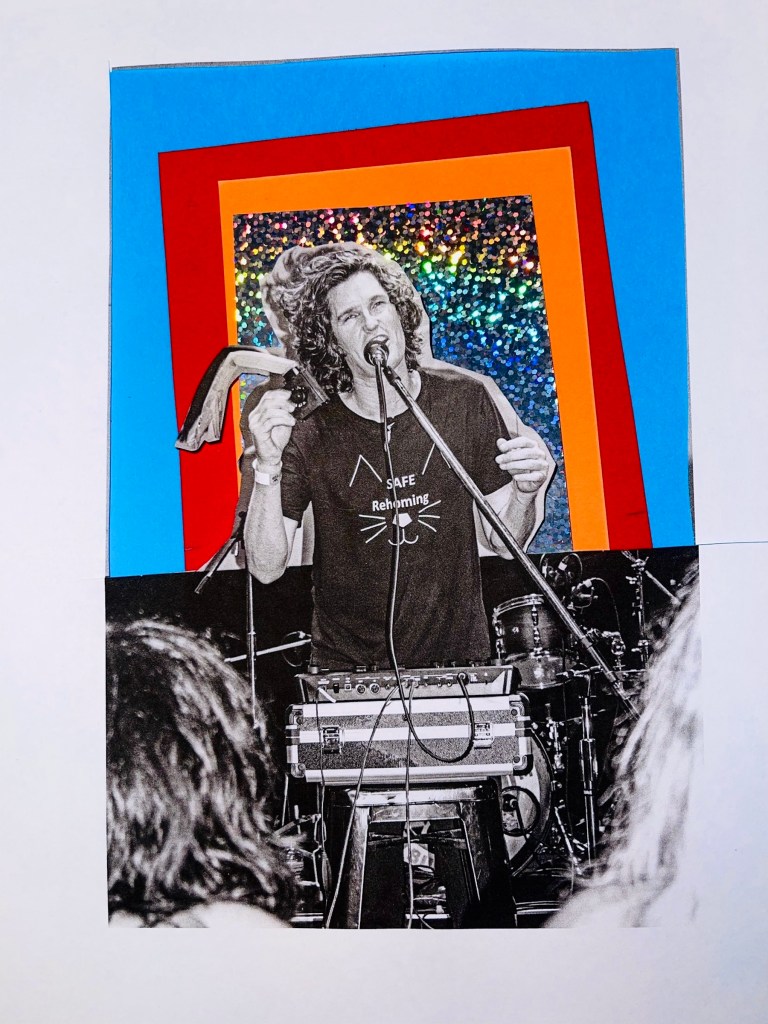

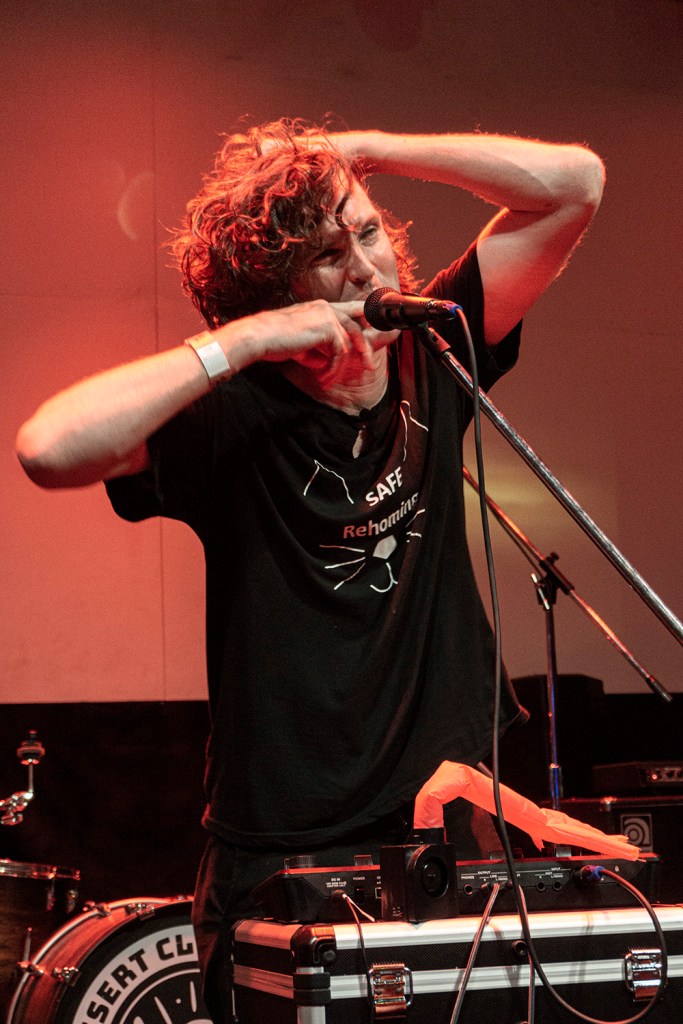

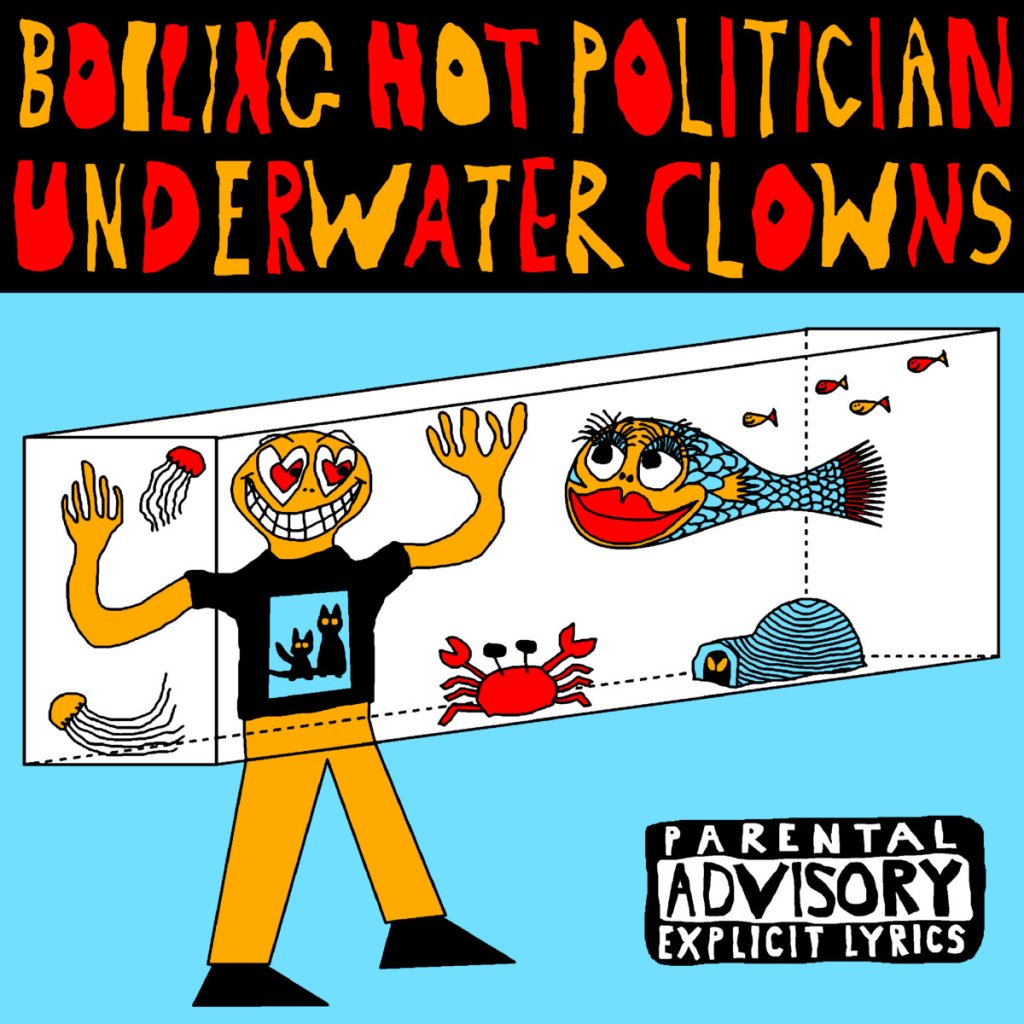

Rhys Grogan is a Sydney skateboarder and self-described “outsider freak musician” creating feel-good bangers under the moniker Boiling Hot Politician. His music pulls no punches, celebrating the good, the bad, and the ugly of life with grooves, emotion, and plenty of silliness. In September, he dropped his sophomore album, Underwater Clowns—a record brimming with ideas and bursting with sheer visceral excitement—recorded at home in 2022-2024 under the watchful eyes of his cats.

Gimmie caught up with Rhys to chat about creating music as a late bloomer, growing up on the edge of civilisation, the skateboarding community, pushing yourself out of your comfort zone, songcraft, reality show MAFS, shaping his record Underwater Clowns, losing friends, the importance of having something to look forward to, and launching his album with a guerrilla gig at the “gazebo on greatness,” the Sydney Harbour Bridge and Opera House as the backdrop. Life might feel like a circus, but Rhys grinds through in his unorthodox style—with a grin.

To be honest, I’ve had a really rough week, mentally. I know many of us struggle with mental health in varying ways, and we all go through bad days, weeks, or sometimes even longer. But I almost cancelled (and I hate doing that) because I was feeling so low, but I chose to push through. I’ve often found that when I do that, good things tend to follow. So here we are.

RHYS GROGAN: Yeah, yeah, I find that too! Like, sometimes you’re really tired, but you force yourself to leave the house, and then that energy and effort comes back.

That’s it! I feel that way sometimes when I’m heading to a gig. I might’ve had a really shit day, and the last thing I want is to go out, be around people, and deal with overstimulation. But when I do make the effort, those nights often turn out to be the best.

RG: Yeah. It’s click selling in brain. I swear, it’s good! [laughs]. Even when you’re zonked.

Life lately has been good but also kind of annoying—work was annoying me because there was too much data in the spreadsheets. It fries your brain a lot. Last week, we went camping for a week by the Murray River. So now I’m back in—I like my job again. It’s good.

What kind of work do you do?

RG: I make maps of trees for the New South Wales government. We try to make computer models that predict where threatened species and threatened plant communities are going to occur. And then we go out and test if they’re working by going to find those plants. I work with good people, and there’s a good balance of office and field.

How did you get into that kind of work?

RG: I did an Environmental Science degree at university, and I was pretty good at maths and statistics. So mapping trees was kind of perfect—it’s just using giant data sets, mashing them all together, and putting them into a model to see what comes out. I find it very stimulating, and it’s great to be able to get out of the office into the field. It’s nothing like making music, but it’s good.

Have you always lived in Sydney?

RG: I grew up an hour and a half southwest of Sydney, near Warragamba Dam, right on the edge of civilisation. My mum and dad still live out there. I was a skateboarder but grew up on a farm, so I was always stuck and isolated with my two brothers. I didn’t appreciate it at the time because we were in the bush. On weekends, Mum and Dad would be out, and we’d be stranded on the property the whole time. I grew up in the country and moved to the city when I was 19.

How’d you get into skateboarding?

RG: A friend got me into it. I started when I was 10, and I’ve been doing it ever since. I’m 39 now, and yeah, my body’s destroyed, but I still go to the skate park a few times a week. All my friends are degenerate skaters—it’s a good community.

Totally! A lot of my friends skate. My family had skateboard shops in the 80s and the 90s so I grew up around skateboarding culture. I wasn’t very good at it [laughs].

RG: I’m not either! [laughs]

That’s not true! You’re rad at it.

RG: I’m okay [smiles].

How do you feel skateboarding helped shape your identity growing up?

RG: It was really good, especially since it was pre-internet. You couldn’t just find music anywhere—you could only hear what was on Recovery or Triple J. But skate videos had all this cool music in them, and there were so many great videos. That aspect massively changed everything because you’d hear all these bands in skate videos, like Sonic Youth or even weird hip-hop groups like Hieroglyphics.

I love Hieroglyphics! Working in a skate shop everyone would come visit and watch the new skate vids, all the 411 video mags; they had the best soundtracks: ATCQ, Mobb Deep, Dr Octagon…

RG: Yeah, it was incredible! You could go on Napster and download all these albums, and people at school would be like, ‘Where the hell did you find this? What is this?’ It was just skate video soundtracks. They were amazing. That really helped shape my identity in a way because, you discover music and musicians, and it clicks something in your brain that changes you forever.

Did you move to Sydney just because you wanted to get out of the country?

RG: Yeah, I got a girlfriend when I was 19, and she lived in the city. I was working a job out in the country, welding handrails. During the week, I’d stay home with Mum and Dad, but I’d spend all weekend in the city with my friends. Then I just moved—I chucked the towel in on my country friendships and made the leap. It was huge for me.

What were things like for you like when you arrived in Sydney?

RG: It was good because I already had a bunch of friends, but day to day, you’d start noticing things happening during the week that were invisible to you before. I used to put so much pressure on the weekend—skating all day, then going to the Judgment Bar or hitting Oxford Street every Friday and Saturday night. The Sunday night drive home was always so depressing, knowing you had five days of horrendous manual labor ahead.

Moving to the city really took the pressure off. I wasn’t an 18-year-old binge drinker crashing at friends’ houses two nights a week anymore. I kind of chilled out because I didn’t feel the need to cram everything into the weekend. It’s hard to articulate, but I guess I spread out my interests more.

The music scene on Oxford Street back then was pretty strong, too.

Yeah. I spent a lot of time in Sydney in the ‘90s and early ’00s because my sister lived there. She had an apartment on Oxford Street and the Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras parade would go right past her balcony every year. There was a bunch of live clubs we’d go to and see all kinds of bands.

RG: Yeah. There was Spectrum back then Q Bar and later was the Oxford Art Factory, which is still there, which is mad. There was this place called Blue Room, it was like the top end of Oxford Street. They used to get any touring band to DJ there, it was a really funny scene. The Brian Jonestown Massacre DJ’d this one weekend, and all these old indie bands.

I just remember being 18 and going to so much live music. You’d get way more FOMO back then because there was no social media. If you weren’t out, you’d have no idea who was out or what was happening. Now, you can just see it all on people’s stories, which is kind of sad.

I remember when I was younger I thought that if I missed a show it would be the end of the world.

RG: Yeah, it still is sometimes.

We haven’t been able to afford to go to as many shows this year. But we go to as much as we can. We really love artists that do their own thing, something different, that pushes stuff further.

RG: Yeah! There’s so much out there—I’m drawn to the weirdos!

Same!

RG: But you know, I’m a “normie” [laughs]. I’m in a government office right now, but just cosplaying being a big freak.

Ha! I get it. I worked for the government at the State Library for ages. From looking at me, people would have no idea that I like all the stuff that I do. Sometimes it almost feels like you have two different lives — the going-into-the-office one, and then all the other stuff you do outside of it. But like you were talking about before, it’s a balance. I’ve found that anytime I’ve had to create stuff for money, I didn’t really enjoy it as much as when I’m making something just to make.

RG: Definitely. Oh man, it would be a nightmare if I had to monetise the music I make—if I was dependent on it. I wouldn’t make much money.

But yeah, the way I make music is, I’m lucky—I’m obsessed with skateboarding, and I’m obsessed with making music. I’m probably obsessed because there’s no money involved. I just freaking love creating it. Sometimes I love performing it, and other times it’s a total nightmare. But that’s all part of the fun—not knowing what to expect.

Recently, I used to be kind of weird about people at work knowing I made music. Then one guy found out, and I thought, ‘Actually, who gives a shit?’ Now I’m an open book. Everyone knows, and it’s kind of funny how it works. I reckon everyone should be an open book.

Even these two guys from work came to one of my gigs a while ago with Our Carlson. They loved it. It was really freeing—I made this weird music with a loop pedal. These two scientists I work with, they have young kids and don’t get out to the city much, but we had the night of our lives. We actually stayed up. It was excellent.

How did you first get into making music? You were in band, This Is Authority. Did you do stuff before that?

RG: I did stuff before that, but not really. I would always find instruments in the street. I made this horrible Olivia Newton-John cover and put it on Facebook—that was the first thing I made: ‘Please Don’t Keep Me Waiting.’

Why’d you choose that one?

RG: Because Crispin Glover sang it in this weird short film series, and I was obsessed with him. I was 25 or something, and I just loved him because he’s a freak. He did this thing where he covered that Olivia Newton-John song, and I decided I would do the same with the instruments I found.

Throughout my 20s, I made silly songs on the computer, but then, in my late 20s, my friend Luke and I started this band called This is Authority. It was really like, ‘This is…’ and then we couldn’t think of anything. We had so many words after, This is, and, This is Authority was what we came up with. It was good.

At the time, I knew nothing about hardware or songwriting or anything—I didn’t even know what a mixer was. I’d be like, ‘What’s that thing you plug your bass and all these pedals into?’ He had all these drum machines and cool synths, and I would drink XXXX Gold and come up with vocal melodies over it. Then we played a few shows, and it was mad.

It was really later in life—we played our first This is Authority show in 2016, so I would’ve been 31. Very late—late bloomer.

Nice! There’s nothing wrong with that. Better late than never. I always think you can make music whatever age, wherever you’re at.

RG: Yeah.It was good because if I’d started earlier, it would’ve probably all been really cringe, like early 2000s indie style, like The Killers or something [laughs]. But yeah, it was really fun. We played for two years, maybe longer.

We’d recorded this EP, and spending summer at his house every week—probably for six weeks. We’d just record, and we had four songs ready to go. Then he called me one day and said, ‘Oh man, I accidentally deleted all the songs.’ I was like, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Yeah, I didn’t know formatting the hard drive meant deleting everything.’ We both just cracked up laughing.

I was like, ‘Holy shit, dude.’ But I was also like, ‘Oh, let’s just take a break, and we’ll get back into it in a couple of months or something.’ But we never did. We might again at some point.

Before that you were just making music yourself on your computer?

RG: Yeah, with my Yamaha keyboard and multi-effects pedal—it looks like one of the ones The Edge from U2 uses. It was fun!

Was there anyone or anything in particular that made you think, ‘Wow, I can make music myself’? Because, you know, a lot of people usually think, ‘Oh, I’ve got to have a band,’ but you were just doing it on your own.

RG: Yeah, actually, there was a defining moment. Dark Mofo, maybe 2013. It was at the main Odeon Theatre. Total Control played, along with some other bands, but at 2 AM, there was this guy on stage. He looked stressed and had all this gear, he was singing and doing techno stuff. Kind of a rave, with people in different corners of the theatre. It felt like a scene from a movie—only a few people paid attention, while the rest danced and talked. I thought, ‘What is this? It was incredible.

It was Lace Curtain, one of the guys [Mikey Young] from Total Control doing a solo thing. He looked really stressed and nervous, but it was amazing. I thought, ‘Oh, shit.’ I hate public speaking and performing, but seeing him so nervous and still doing it made me think, “No one cares, and it’s incredible.’

That was probably the main thing that made me think, ‘I could do that.’ I wanted to make music with electronic gear—not just use a laptop and press play, but do something creative on stage. Even if you’re freaking out, it adds to the show, rather than seeing a confident person engaging the audience. I guess I identify with the nervous wreck.

I saw him again later in Sydney—still nervous, still great.

You don’t really seem very nervous performing, like at The Mo’s show you played up here on the Gold Coast at the the beginning of the year with Antenna and Strange Motel.

RG: That was a crazy night. Benaiah [from Strange Motel] organised it; I’d never met him before. When we met, we chatted for ages. He was really interested in my gear and said he wanted to do solo stuff. I knew he was in that band Sex Drive—they’re a really cool band. They came and played festivals in Melbourne and stuff.

I thought, Cool, I’m this outsider skateboard guy, and I’ve met this cool guy. It was exciting. We even talked about playing a show in Sydney in a months time.

But then he died that night. It was horrible—such a bummer. I couldn’t believe it. The next day, I had this very weird feeling. You make a new friend, it’s exciting, and then you find out they died. It was bizarre and awful.

We couldn’t believe it when we were told. We’d just seen him a few hours before. He gave us a huge hug and was so stoked we came to his show. He used to live near us and would come over. He enjoyed talking to us, probably because we were outside his usual crowd. I know he was dealing with a lot at the time, so we’d just talk about music and art, trying to encourage him towards the positive stuff. Like you said, he really wanted to focus more on his own music. He was looking forward to so much, and then, suddenly, he was gone. It was heartbreaking.

RG: So sad. Yeah, that was crazy. He is the G.O.A.T.. I’m very happy I got to meet him. Very sad that he died that night, it freaks me out still.

Yeah, he really made an impact on everyone he met. I sometimes imagine what kind of music he’d be making if he were still here. To go back to what we were talking about, your sets are so much fun, and you can really see that energy transfer to everyone in the room. It’s a great vibe.

RG: Good—that’s what I want. I’m like shitting my pants until I just press the first button and then it’s all fine, normally. But a lot of times, I stress out so much for a gig that I’ll make myself sick. About 40% of the time I play, I get the flu because I’m stressed leading up to it. But it’s always fine. Even if I’m sick and my voice is squeaking.

How did you get from ‘I hate public speaking’ to ‘I’m in front of everyone playing these songs I wrote’?

RG: It was like a personal challenge, in a way, because I remember when Luke and I started, This Is Authority. He suggested, ‘Let’s make a song’ and my first instinct was, ‘Absolutely not! There’s no way, I’m not going to die.’ And I was going through this thing of getting out of my comfort zone and forcing myself against that instinct — that intrinsic freaking out, that repellent feeling of not wanting to do it — and knowing it was going to be okay.

I saw on your Instagram, you wrote about how you had a feature in a skateboard vid and you said in your post, ‘Thanks to my friends for bullying me into doing these tricks.’

RG: Yeah. Yeah! Well, that’s ‘cause all the other skaters in that video are a lot younger than me. I’m like the older guy tagging along with them, and they would literally trick me into doing these tricks. They’d claim like, ‘Oh, you should do a trick down this rail.’ And I’d be like, ‘Oh, no, no, no, that’s ridiculous.’ And they’d be like, ‘Let’s just go look at the spot.’ I’d go, ‘Alright, we’ll go look at it, but I’m not going to skate it!’ And we get there and they go, ‘Well, we’re here now, so…’ Then I’d be pressured into doing it and it just works out.

I guess, it’s the same for music. Like if you agree to play a show, then you hang up the phone and you’re like, ‘Shit, what have I done? This is a nightmare!’ Then the day comes and you’ve got no choice. Nine out of 10 times it works out. I kind of enjoy the pressure put on by doing it to yourself just against your own will. It’s not therapy, but it’s always just coming out the other side better.

Seriously, every time I play a show, a couple of hours before, I’m in my head screaming, ‘WHY HAVE YOU DONE THIS TO YOURSELF?’ I’m looking in the mirror going, ‘You idiot! What have you done?’ But then, you start playing and it’s fine.Or sometimes it’s not, but that’s still fine.

Speaking of playing, you launched your album recently by playing in the Observatory Hill Rotunda, after the venue you had booked fell through.

RG: I won’t name them because I don’t want to throw them under the bus.

Of course. You got bumped for a wedding?

RG: Yeah. I got bumped from the pub because someone was like, ‘I’m so sorry, man. My boss is overseas and someone has offered us four grand to hire the pub, they said they’d spend four grand on booze for the wedding. I can’t say no, I’m really sorry.’ It was a couple of weeks before it was supposed to happen.

When skateboarding was in the Olympics, I’d already taken my TV to the rotunda, plugged it in because there’s a powerpoint there, and we watched the skateboarding on the screen. And between heats, we sang karaoke and had a really fun time, no security came. Nothing happened to us. The Harbour Bridge was right there. It was incredible.

So I just thought, alright, screw it. I’ll borrow Trent’s speakers from Passport, get this PA, and set up a big projector screen. I’m going to play a gig at the rotunda with the Harbour Bridge in the background!

Last time I released an album, I had no gigs, and it just came out—no launch, nothing. It felt weird, this time I felt like I had to do something. So I did that.

It was good because there was no venue asking, ‘How many tickets will you sell? How much money will you make?’ Once you take the money out of it, you can do whatever you like. I thought I might get arrested, but it wouldn’t be a big deal. It’d even be funny if I got shut down by the police since I wasn’t charging tickets. Worst case, I’d get a fine, and people would think it was funny.

But it went off without a hitch. Three bands played 90 minutes straight of really loud music. A guy from the Observatory stuck his head over the wall, nodding along—he was into it. It was freaking amazing!

It looked amazing! The photos photos I saw from Dougal Gorman capture it beautifully, and it looked like such an incredible time. I got warm, happy feelings from just seeing the photos.

RG: Yeah, that’s that thing. On the day at first, I was like, ‘What have I done? I’m going to get arrested and it’s going to suck.’ I thought the wind’s going to blow over the projector screen, but it all worked out. It was so sick. Everyone said like the vibes were amazing. The atmosphere was incredible.

What is one of the things that you remember most from the day?

RG: I hugged everyone who was there!

Awww, I love that!

RG: It was my friends’ band, Hamnet’s first gig ever and like, it’s pretty amazing to say that their first gig ever was in front of the Harbour Bridge near the Sydney Opera House at an illegal show with a projector screen. It pissed down with rain about an hour beforehand and then it just stopped. It was all meant to be.

The universe was on your side.

RG: It seriously was. It was unreal.

It worked out way better than just playing a regular pub gig.

RG: Oh yeah! Everyone was saying that, and they could bring their own booze. Afterwards, we cleaned up all the rubbish, of course. It felt like a miracle. I’m still trying to work out if that was the most epic venue ever. I’ve been trying to think of other places that could top it, but I can’t. It was the most epic, beautiful outlook place. Maybe next time I could go the opposite way and play in the sewer, like the most disgusting place [laughs].

The DIY drain shows we see happening occasionally in Naarm/Melbourne always look like a whole lot of fun.

RG: Yeah, I’d say there needs to be a bit more of that in Sydney.

So you were launching your latest album, Underwater Clowns. It’s really got such a unique energy to it—we LOVE it! It’s one of our favourite albums to come out this year.

RG: Thank you. As I started recording music super late, that might be why it sounds like that. It’s a mashup of everything I’ve liked since I was a teenager. I swear it’s a bit of insane, repetitive techno, a bit of Britpop maybe. It’s just a mix of all the stuff I like, and it somehow comes together to make this weird noise.

You can definitely hear that Brit pop-style in some of the choruses.

RG: Yeah. In the ‘MAFS’ song. It’s meant to be like an old pop song. It doesn’t really sound like pop, though.

I started trying solo stuff around the time This Is Authority ended. My brother, who I used to live with, got his girlfriend pregnant and said, ‘I’ve got to move out because I’m having a baby. Do you want to borrow all my music gear indefinitely?’ I was like, alright.

So I ended up with a drum machine, two synthesisers, and a mixer. I didn’t buy anything—just plugged it all in, barely looked at the instructions, and mucked around with it. The only thing I bought was the looper pedal, which I used to tie it all together.

Maybe it’s that ‘mucking around’ approach that comes through in the final product. It sounds like someone drinking XXXX Gold, fiddling around, and trying to make songs they like. It’s a ‘mucking around’ aesthetic.

There seems be so many textures on there. And all these different emotions. I noticed there’s a character Mr. Hogan that turns up in three songs; was there a concept happening there?

RG: That’s a really funny name because I always call my friend, Mr. Hogan, like when we were young, we had no money and we’d go skating. We used to always go to Hungry Jack’s cause I had this app and you could win free stuff. And we used to call Hungry Jack’s, Hogan’s. It’s just this dumb thing with my friends. I’d call my friend and would say ‘How are you, Mr. Hogan?’

I swear that there’s that documentary about the guy who founded McDonald’s and he says, ‘The reason McDonald’s is so successful is because the name McDonald is so Americana.’ And I swear that Hogan is the Australian version of that. There’s something funny about it.

Sometimes you get songs stuck in your head that are just made up and it doesn’t exist yet, so you have to make it, you muck around with gear and try to make something until it sounds like what’s in your head. That’s where heaps of the song come from. I’m sorry I don’t have a better explanation for what that, but that’s actually just what it is. Mr. Hogan is a silly name that keeps coming back into my head.

There’s ’Feed Me Mr. Hogan, ‘Mr. Hogan Workplace Assault’, and ‘Mr. Hogan Loses The Plot’.

RG: Yeah. ‘Mr. Hogan Workplace Assault’ is fantasising about paying someone to come into your work and beat you up so you can get out of work. It’s a mythical character, and they both end up in jail in the song.

Does that ‘I wish someone would come beat me up so I don’t have to go to work’ thing come from a real place?

RG: Oh, yeah! It’s about being too scared to take a sickie ’cause you think you’ll get caught—so you do something really elaborate instead. It’s so dumb. But, that song was made because…I’ve got this club, and we call it Feed Bag. I’ve got these friends who make techno music, and I don’t understand most of it. It’stooavant-garde noise music. These guys—Luke, who was in This Is Authority, and my other friends Tristan, Jerome, Tom, and my cousin Nick—are in the club, and you’ll go home, make a song by yourself every week, and then we all get together and everyone plays their song, then you get feedback on it. You kind of get roasted, but you get good feedback too. We do this every couple of weeks.

‘Mr. Hogan Workplace Assault’ was one of those songs. I came home, had 40 minutes to make a song, and made the skeleton of it. The first iteration was just me saying, ‘Mr. Hogan, won’t you beat me up at work,’ over and over again. I recorded all the loops in 40 minutes, then changed a couple later when I put it on the album.

It’s good having this club that forces me to make songs. Like you said before, sometimes you’re tired or feeling down, but with the club there’s this pressure—you don’t want to show up without a song. It’s allowed, of course, but the point is to find something. Sometimes you just make something without feeling that itchy inspiration, and it does turn into something. It’s freakish.

A song I dig on the album is ‘Consumed by Brucey’.

RG: I just saw a picture of Brucey—Bruce Lehrmann—in the news. He’s horrible. The song is about how sometimes you think back to a time in your life, and you tie it to something significant that was happening at the time. Like, I’ll think, ‘When was that gig?’ and I’ll go, ‘Oh, yeah, it was right before Bruce Lehrmann got sentenced.’

Now, historically, I’ve got this stupid, annoying connection to Bruce Lehrmann because I was seeing his face everywhere—on TV, on my phone. I ended up using that to reference when and where I was, and I hate it. I constantly have to think about him. So I just wrote a dumb story about it.

The song is about someone who keeps dying and respawning as some kind of seafood. They get eaten by Bruce Lehrmann, and Bruce vomits them up on a reporter. Then they die again and respawn as a mollusk, only to get thrown in a kitchen bin. There’s a TV in the corner, and all you hear is Bruce’s whiny voice on it.

It’s silly, but it came from that frustration. Like, whenever I think about my friend dying, I tie it to the 2019 bushfires. Or I’ll think about something else, and it’s linked to another significant event I don’t want to remember. Sorry—I’m just unpacking all this now for the first time.

After the first album, I ran out of meaningful lyrics so now it’s all just this stream of consciousness rambling.

In the chorus of that song, you’ve got the lyrics: ‘Every time you wake up, there’s an awful new surprise, and everything you try to grow eventually dies.’ It always gets stuck in my head.

I related it to how you wake up every day, and there’s something awful and new on the TV or happening in the world. And then there’s the fact that, well, eventually everything you love—and everything that does grow—will die, because that’s the cycle of life.

For me, it had a deeper meaning. I mean, yeah, it has absurd imagery and other stuff around it, but that line really struck me.

RG: It does tie into that because it’s about reincarnation. I try not to collect heaps of stuff because the thought of someone having to throw it out or give it to Vinnie’s one day when I die, really creeps me out. That’s exactly what it’s about.

Even at work, there’s a screen in the elevator that has news and ads on it. When I’m looking at it, I’m already thinking about what’s going to be on it next. I’m like, ‘Oh, tomorrow it’ll be some other crap.’ And in the long term, it’s all going to be gone and forgotten.

I’m glad you like that line, and I’m glad people interpret it in their own way. It frees me up because sometimes I’ll listen back to it and think, ‘That is what it means,’ even though I don’t know where it came from.

Things can totally have different meanings. They don’t have to just have one. People always bring their own experiences to whatever they’re looking at. Like, how many times has something terrible happened to you, and you’ve listened to a song and thought, ‘Oh my God, they get me,’ or, ‘I get this.’

RG: Yeah, definitely. It’s so good!

‘MAFS’, the song you mentioned before, is a really cool song too. The sample at the beginning is from the movie Lost Weekend, right?

RG: Yeah, right when I was finishing the album, I was drinking too much, not in a good way. The sample doesn’t really have much to do with the song, but it has something to do with me. The line says, ‘I’m not a drinker, I’m a drunk.’

I wanted to put that in there—it reminded me to slow down, stick to mid-strength, and get therapy. I’ve always liked albums where there’s a weird clip from a movie or something between songs. I enjoy that kind of thing.

Same. I can see what you mean, with the movie being about the difference between casually drinking, being consumed by it, and it becoming an addiction. The emphasis on self-awareness.

RG: YeahIt was funny because I didn’t have a song specifically about going overboard on the sauce. So I just put it at the start of ‘MAFS’ because it fit there, right before the end of the album. Now, every time I hear it, I’m like, ‘Oh, note to self—seriously.’

The cultures we grew up in—skateboarding and music—definitely have a big drinking and drug culture. It’s really ingrained, and that can eventually cause a lot of suffering, whether people like to admit it or not.

Often, you’re attracted to those subcultures because you struggle with life or you’re very sensitive. When we’re out with our mates doing these things, it feels like it helps—and maybe it does, for a while. But from my own personal experience, and from what I’ve seen over the years, those things can get really toxic. You end up in a lonely place, and I don’t think society really talks about this stuff enough.

RG: Definitely. It sneaks up on you. As someone with severe social anxiety, you drink more to try to feel less anxious, and it never works. You’re just constantly putting a lid on it, constantly struggling with that.

I haven’t hit total rock bottom, but it’s something I always have to be mindful of. It takes time—it really does. Sometimes, you just have to realise that you’re the only person who can make changes for yourself.

Yeah. People can tell you and remind you forever, but sometimes, it’s just about having that moment when it clicks.Like, I don’t not drink, but I haven’t had a drink in a really, really long time. I can go out, have fun, and not do all those things. And I actually remember stuff. I’ve been seeing live music since I was a teenager and I don’t really remember much because I was having way too much of a good time.

RG: Yeah, I’ve got way too many of those ones too. It’s not good. I wish I could remember that stuff.

I know in June you played a show in Naarm and it raised funds for suicide prevention and the Black Dog Institute; what made that particular gig significant for you?

RG: That was really significant. I’ve had a bunch of friends die, a couple by their own hand. Actually, it was crazy, that night, I found out after I played that a friend had taken his own life, so that was shocking.

Oh, man, I’m so sorry.

RG: Horrifically ironic. Gigs like that are really important. It’s so annoying, I’ve lost two friends to suicide this year. Sometimes it does feel like pissing on a bushfire. Sometimes I think, if my friend Harvey and my friend Jack had just committed to getting proper help… [voice trails off; reflects] …I’m sure they tried.

It can definitely be hard to reach out and get helps sometimes when you’re in a bad place…

RG: Yeah. I’ll never stop playing gigs like that one because you have to do whatever you can to raise awareness and support these places that help people. Every time it happens, you mentally go through a list of people in your life that you think might be susceptible to these things. You just have to do what you can to make this stuff stop happening or curb it as much as possible.

Of course, I’m going to play that gig. It’s important to me just because… my friends’ deaths, at this point, has almost become numb and boring. It’s like, oh, right, another… We have a routine now. It’s scary when it’s gotten to a stage where a death in the community has become part of the routine checklist. It’s messed up.

There’s only one song I’ve made in my life that expresses sadness over a friend dying. That was on the first album, about a friend, Keggz, who died of a heroin overdose.

The last song on the album?

RG: Yeah. I remember it like it was yesterday—when Sydney was full of smoke in 2019 because of the bushfires. We were at Taylor Square, our skate spot, and it was so smoky. Everyone was crying and feeling sad. It was awful. But, you know, it’s those times that can make you realise how lucky you are to have such a big community of friends. That’s the silver lining. Sorry…

No need to be sorry, I get it. That’s one of the things I’ve always loved about the skate community. Having a shop, people would come in and just hang out, watching the skate vids with us. Often, a lot of the young dudes would start talking to me, sharing whatever their troubles were. Being a little older, I’d be able to give them advice, or at least point them in the right direction. It’s something I’ve always really loved about the skate community—there’s this real camaraderie.

RG: Yeah, it’s incredible. The only downside of being a skateboarder growing up in the 90s or 2000s is that 97% of my friends are male. But it’s changed now in skateboarding, which is freaking great!

Especially with the Olympics, and the visibility it brings. When people see stuff on TV, it really reaches a whole other audience. I remember growing up, waiting in my family’s lounge room sitting on the floor right next to the TV screen to watch Nirvana Unplugged, before the internet was a thing. Those events felt special. It was such a big deal for me!

RG: Yeah! Watching Recovery on Saturday mornings, not knowing what band would come on next. And Rage—holy crap! Life changing.

Totally. Where did the album title Underwater Clowns come from?

RG: You know when you’re a kid, and you go to a Chinese restaurant, running around like an idiot while your parents are getting drunk? As a kid, you’re pressing your face against the fish tank glass when you’re bored and freaking out because the fish look ridiculous. That’s where it comes from.

And the other part is, I kind of love clowns too—not in a spooky, nu-metal way. Clowns are cool, and they get a bad rap. When Halloween comes around and people talk about evil clowns, I can’t stand it. I think clowns are amazing. Maybe I identify with them. It’s one of those recurring things. All my friends are like clowns, but yeah, it has that childhood significance—being freaked out by exotic fish and just that memory. It’s special.

I love how you take all these different aspects of your life and put it together in this way that’s really unique, and it forms these interesting narratives.

RG: It seems to work out. It really takes effort.

What’s the story of the last song on the new record, ‘The Factory Farmed Panel Show Disorder’? I ask because that was the name of your last album.

SG: It’s about panel shows like The Gruen Transfer, The Project, and all the others like Good News Week. And then there’s QI—I can’t stand it. There’s something in me that just doesn’t like when people are paid to be clever, and we look to them as our intellectuals, like people we should admire. It bothers me when you catch someone repeating something they’ve heard on Good News Week or The Gruen Transfer or even Q&A—it’s like they’re identifying with that rather than having their own thoughts about it. It’s not bothering to think critically because someone else is offering the opinion for you.

Whenever I turn on the TV and a panel show is on, it just annoys the hell out of me. There’s this disdain I feel for these public intellectual figures, like Ben Shapiro. I remember seeing people on a bus watching weird right-wing streamers, or YouTube videos, the ones that just spew nonsense. They consume it and adopt their exact views. There’s one called Tim Bull, and he’s terrible. I call it ‘Factory Farmed Panel Show Disorder’ because it’s like a disorder—regurgitating stuff that you hear without thinking. It’s pretty cliché. There’s this smugness about these shows, this cleverness they try to give off.

Looking at news sites, I always find the stories are either about something horrible happening in the world, something clickbait to make you angry, or something that just reinforces terrible ideas and behaviour for people.

RG: Definitely. People watching TV on planes and buses creeps me out. YouTube videos. It’s a nightmare to me.

What can you tell me about the song ‘Wombat Online’?

RG: People like that one. That started ’cause it was one of those songs I had to make in a rush before going to my music club, but it came together more later.

Did you get good feedback at your club?

RG: Yeah! It used to have a completely different chorus, but I swear, it started as a line in my head: There was Joseph Kony at the door, he’s bought a rancid leg of lamb, and I am on the menu. I am last year’s Christmas. But I didn’t know what it meant. I just thought it was dumb. It’s kind of about goofing off in the metaverse.

I saw that story about these Japanese teenagers who refuse to leave their rooms or participate in society. And it’s like that line: your mother slaps you in the face, you tell her that you’re fine. It’s also about Joseph Kony, a wombat and a guy driving around in the metaverse, goofing around. You need a bit of silliness, a bit of emotion, a bit of groove, and you can make cool songs.

My songs are all so metronomic, and I don’t know if there are many cool changes. I had this other song I liked the chorus of but hated the verses and synths. So I just took the chorus and slapped it into this song, and it worked perfectly. That’s why I love making music—you can muck around and occasionally create something you really like, and there are always a few freaks who’ll like it too. It helps me work stuff out too.

There’s that great lyric too: what’s the point of getting up if you spend the day online.

RG: That’s me every day. It speaks more to the teenager who won’t leave his room. I feel like that a lot. I don’t work from home much, but when I was drinking more, I was just being a slob. My alarm would go off at 8, but I’d get out of bed at 8:57, turn on my work computer—my “terminal” because it sounds dystopian—and just sit in the living room, not talking to anyone all day. If my mum were there, she would’ve slapped me. I don’t live with her anymore, but you get to a point where you forget the day, the month, everything. It all blurs, and the only way to track time is by horrible news or events like bushfires or floods that remind you where you were. It’s so weird.

I thought the song ‘Job Wife Self Life’ almost sounds like a mantra. Like you’re trying to tell yourself that you love these things, trying to convince yourself.

RG: Yeah, I wrote it on the train during my divorce. That was my mantra before COVID, when I was going to the office every day. I’d repeat it to myself: I love my job. I love my wife. I love myself. It helped. Years later, I turned it into that song, and people really like it. I still need to work on the live version, though—it kind of goes nowhere. I put it in the middle of the album because it feels like an odd song that separates the two halves of the album.

You worked on this album over two to three years; were there any other big things that happened in your life that helped shape this album or the songs?

RG: Friends dying, getting a divorce—those are big things. They’re all in there somewhere. I started watching Married at First Sight with my girlfriend. People shit on it, and they shit on the people who go on it. But some of these people just want to find love. Sure, they might be a bit narcissistic, wanting social media followers, but everyone’s a bit of a narcissist.

Sometimes, they get absolutely destroyed by the show—paired with awful people, ridiculed, and laughed at. It’s horrible. I watched a lot of Married at First Sight, and it inspired at least one song. It might spill into others. The culture of laughing at reality TV stars is very dark.

It’s kind of weird that people get pleasure and entertainment from other people suffering.

RG: Yeah. I feel sorry for most of the people on there. It’s horrific. I’m sure most of the people on that show come out in a very dark place with mental damage. It’s not good.

I noticed that on the album, even though songs might be darker, it has moments of happiness and fun, with all the shimmery synths and parts and all these really cool little quirky noises you put in there.

RG: You want to make it feel hopeful. There’s a lot of terrible stuff, but there’s also a lot of real silliness, and I like finding that in things. Laughing at yourself is important—it’s about just enjoying it.

I’m a big fan of music that makes you feel hopeful, that makes you giggle, that makes you feel something. I listen to a lot of Underworld,I think it’s uplifting. I’m not great at playing synths, but I love chords that make you feel. In ‘Factory Farmed Panel Show’ it gets me really pumped up! I don’t know, there’s probably a musical theory way of explaining it.

Song ‘Feed Me Mr. Hogan’ has a real rave-y vibe, and it took me back to when I used to go to raves, doors, and warehouse parties with my friends.

RG: Funnily enough, it was for the feedback club. I was listening to two songs on repeat at the time: ‘Past Majesty’ by Demdike Stare and ‘Me, White Noise’ by Blur. It’s actually those two mashed together. It doesn’t sound as good as either of them, but it’s got that really silly vocal with long delays going in and out.

‘Past Majesty’ has this thrash-y, techno, repetitive vibe. I don’t go to the gym, but you could definitely run to it or something. That’s the feeling I wanted.

I swear, everything I love is sloppily slotted in there a bit. There are traces of it—DNA of it.

You don’t have to classify yourself as much these days. Younger kids have way less pressure to pigeonhole themselves into little groups. It’s mad.

Making music is just DIY mucking around, like a kid would do. It sounds a bit like a kid made it, which is good. I love that—it’s got those moments of wonder where you’re listening and thinking, What the fuck is he doing here? But you love it. You’re try to work things out, but you can’t, and that’s okay. You just go with that.

It’s like seeing someone having the time of their life—it’s infectious. Like when you see Crispin Glover on David Letterman, goofing around, being an absolute maniac. You can tell he’s having the time of his life, and it makes you want to be a bit of a maniac too, to let go and enjoy yourself. Some of my songs, at least, might make people feel like that. Throw crap at the wall and go ape!

I didn’t make music for ages because I was like, Oh, I’m a skateboarder guy. I’d see bands and think, They’re musicians. That’s them. I’m me.

I was always such a mega, mega, mega fan of music. I thought everybody—when they were walking home—would purposely take six hours just so they could listen to a song

150 times in a row. I thought that was normal. But then I realised it wasn’t [laughs]. Not everyone was constantly coming up with silly song ideas in their head all the time.

When I started making music with Luke, he was like, ‘This is mad!’ And I was like, ‘Oh, right.’ I thought, oh, you just get some cheap gear and goof around. It’s heaven. I love doing it!

I’ve got two albums on the internet now, and about 70 songs sitting on my computer, that suck [laughs]. But you know what? You have to do it.

Another thing I love about what you do is the artwork that accompanies your music!

RG: I love doing that.

You do that yourself?

RG: Yeah. When I was a kid, I always mucked around in MS Paint, and I loved it. It’s just me drawing in MS Paint now—they kind of look the same, with the black at the top. I could have gotten someone else to do it, but… I’m a real control freak.

And I’m also really passive-aggressive. I hate confrontation. If another artist did it and they made something I didn’t quite like, I’d hate to say no. That would be a nightmare.

That’s why I’m really bad at collaborating with people. I can’t do it. I want things to be my way, but I’m also too much of a people pleaser to disagree. If they said, Oh, we should take this out, I’d be like, It’s fine. It’s fine. Then I’d go home and cry [laughs].

I actually made a song with Ben from C.O.F.F.I.N the other day and we had a freaking ball! Maybe I’ll make another one with him, it was heaps funny!

Where did the name Boiling Hot Politician come from?

RG: When I was a kid— not so much now, but like you’d see on TV— there’d be an election coming up, and there’d be politicians in Dubbo, somewhere really hot in summer, and they’d be wearing a suit. Now, they wear the Akubra and the RM Williams, with the sleeves rolled up. So it’s more normal, but they used to always wear a suit and tie, even on a 35-degree day. They’d be kissing babies, shaking farmers’ hands, and it just seemed so stupid. We live in one of the hottest climates on Earth, and formality just feels dumb.

I really love the name Tropical Fuck Storm because heaps of people don’t like it. It’s abrasive and kind of horrible. Boiling Hot Politician is about sweaty politicians. I saw my friend Mike the other day in Melbourne, and he said, ‘Oh yeah, my friends were asking. They saw your name on a poster, and they didn’t know I knew you. They were like, ‘Who the fuck is boiling a politician? What the hell is that?’ It sounds dumb, and it should be silly.’ I like how silly it is.

When we saw your name on the Nag Nag Nag fest line-up last time when went, it really piqued our interest and sounded like something we’d be into.

RG: I was so nervous because my friend Jackson, who’s in Split System, was speaking to me about it. I was like, ‘I’m still a big outsider-freak musician, and that’s the cool festival. I don’t normally get nervous for gigs, but this is the cool one! I’m freaking out.’ That was such an honour to play.

Steph and Greg are the best. I can’t believe people like that exist— because otherwise, nothing would happen. That was such a fun day.

Nag Nag always is. We love Greg and Steph!

RG: Oh my God, I’m trying to think back— when was it? It was when freaking Prince Charles was getting coronated. I was sitting there, pretty drunk, downstairs, just shaking my head, watching that ceremony, thinking, what the hell? This weird thing was happening, while upstairs, cool stuff was going on.

You have a tattoo that says, ‘Politicians make me sick’?

RG: Yeah. I got it ages ago because I wanted it when I was like 18, and then, years later—15 years later—I still wanted to get it. I don’t have many tattoos; I’ve got, like, three. I got it off my mate Greg, and I love it. My girlfriend wasn’t happy when I got it, but yeah, it’s just silly.

I’m called Boiling Hot Politician, so everyone expects me to have all these intellectual political arguments— not music. But it’s more like I’m a politician because I’m just avoiding conflict, not really saying anything meaningful, and just trying to gain positive attention.

Oh, I’m pretty sure you say a lot of meaningful things, maybe even more than you realise.

RG: Thank you.

You mentioned before that making songs helps you; how?

RG: It helps me massively and helps me work emotional things out. It sounds cliché— like you’ll just blurt something out while you’re trying to get lyrics going. Then the next day, you’ll think about it and go, hang on… oh, right, that’s what that means. It’s spooky, it’s subconscious.

I’m trying to think of an example. Oh, yeah, the lyrics— what’s the point of getting up when you spend the day online? That just kind of came out without thinking. It’s weird stuff like that; you put it together later.

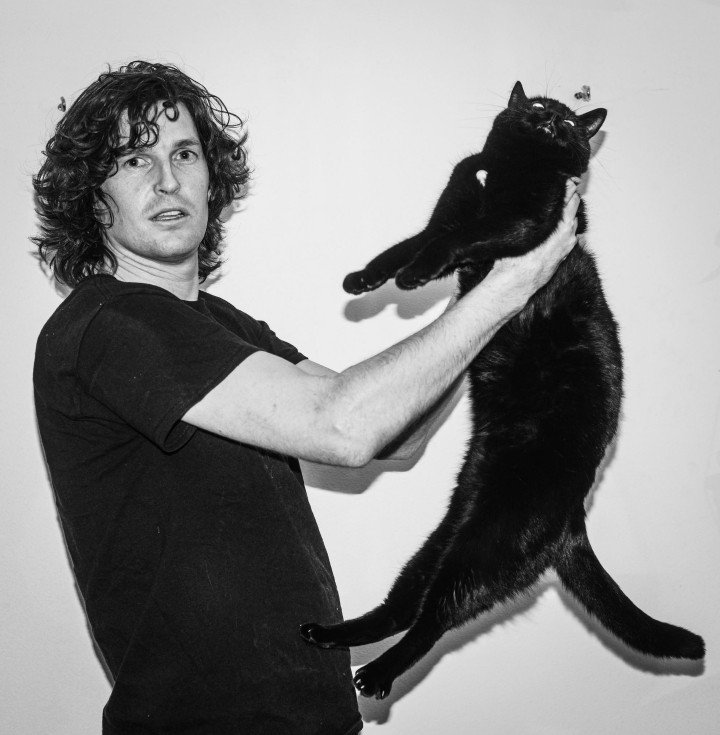

I wanted to ask about your black cat— I’ve seen them in many photos with you.

RG: There’s two of them! Herman and Crumpet!

Aww cute! How did they come to your life?

RG: I’m pretty bad at communicating and expressing my emotions— like every middle-aged man [laughs]. I adopted the cats separately, and they often wrestle and fight each other. They’re like my little brothers, and having unconditional love is kind of a cheat code for giving yourself meaning. I care about them so much, and I know they care about me.

It’s very funny living alone with two black cats. While I’m writing music, they’re always annoying me. Lyrics are the hardest part, so I’ll just be playing a loop really loud in the living room, holding a cat above my head, trying to sing to him. He’s just staring at me like, let it come out of you, and it puts me in such a silly mood. They’re actually getting involved in the writing process— against their will. It makes the whole scene feel absurd, and I think that absurdity gives the music the aesthetic it needs. Sometimes it really does sound like a maniac trying to talk to an animal.

I talk to them constantly and nut out ideas with them. It’s actually really good. One time, I was in this insanely big, important work meeting— presenting this map to a branch leader, something I’d never done before. My cat just started pissing on my drum machine. There were all these really important people on the call, and I had to say, ‘Excuse me, my cat is pissing on my drum machine.’ They were like, ‘What?’ I pulled my headphones off, grabbed him, and put him out on the balcony.

When I came back, they were all laughing. It really broke the tension, and I felt way less nervous after that. They didn’t care. It was funny. Maybe my cat was trying to sabotage me or destroy valuable equipment— my little brother being chaotic— but it was kind of special because the drum machine didn’t break. It smelled a bit for a while, but the presentation went way better. Everyone was really impressed with the science behind my work.

Living without them is hard to imagine. I got them when I was about 30, so, nine years ago. They’re such a huge part of my life now, and imagining the time before them feels weird. It’s like trying to remember before you existed— a pre-cat and post-cat existence.

I’ve only recorded music since getting the cats. So, probably, without them, I wouldn’t have done it.

Do you have any trepidation about turning 40?

RG: Not anymore. I used to— maybe because of skateboarding— since your body turns to mush and you already feel super old when you’re 27. After that, everything’s funny.

I’ll keep making music forever. I don’t have any self-consciousness about being a 40-year-old band music guy. I feel good about it. As long as you can still be silly and not take yourself too seriously while making music, you’re fine. That would be the death of me— if I started to take it really seriously.

It’s only going to get sillier, I think.

Amazing. We’re totally here for it!

RG: Do you have any trepidation about getting older and stuff?

I’m about to turn 45, and I didn’t even think I’d get here, so I’m pretty thankful for everything and every day. I’m constantly inspired by amazing friends and creative people around me, I pretty much make stuff every day, and I laugh a lot. I still feel wonder and excitement like I did when I was a kid, so I don’t really think that much about getting older. Working on my book, Conversations With Punx, I spent a lot of time thinking about life, purpose, what I value, and processing the death of my parents; I got a lot of solid spiritual advice from my punk rock heroes.

RG: That’s so good! You’ve asked so many people about life— it’s freaking incredible. I’ve decided not to have kids, and I’m like, so what will I do? And I’m like, well, I could do anything. And so, you really do anything.

You put on gigs at the rotunda, you attempt to skate around Port Phillip Bay and don’t make it. You always have something silly to do, and you can get so much out of life— it’s incredible.

Are you going to get to go try and skate around Port Phillip Bay again?

RG: Last time we made it to Sorrento, we got cheap flights to Avalon— like 50 bucks return. Then we just walked out of the airport and tried to skate anti-clockwise around it. We skated 70 kilometres on the freeway in the pouring rain. Then I took my shoes off, and they were filled with blood. I don’t know what happened.

Wow. What did you get from doing that?

RG: Just something exciting to do— that’s what makes life worth living. Even though we crashed and burned, I think that’s what’s important: always having something you’re looking forward to, something you love doing, and something you’re interested in. It’s freaking heaven.

Follow @boilinghotpolitician and LISTEN HERE.