Lena is a force of nature—an advocate, researcher, and community builder whose work spans music, activism, and disability justice. From creating zines to process grief to putting on shows that strived to reshape Meanjin/Brisbane’s punk scene by prioritising non-male artists, to her current efforts in preventing violence against women with disabilities, she is driven by a deep commitment to change.

She’s not afraid to talk about hard things like death, power, and systemic inequality. Lena challenges the status quo through grassroots organising, academic research, and award-winning advocacy, carving out space for those too often overlooked.

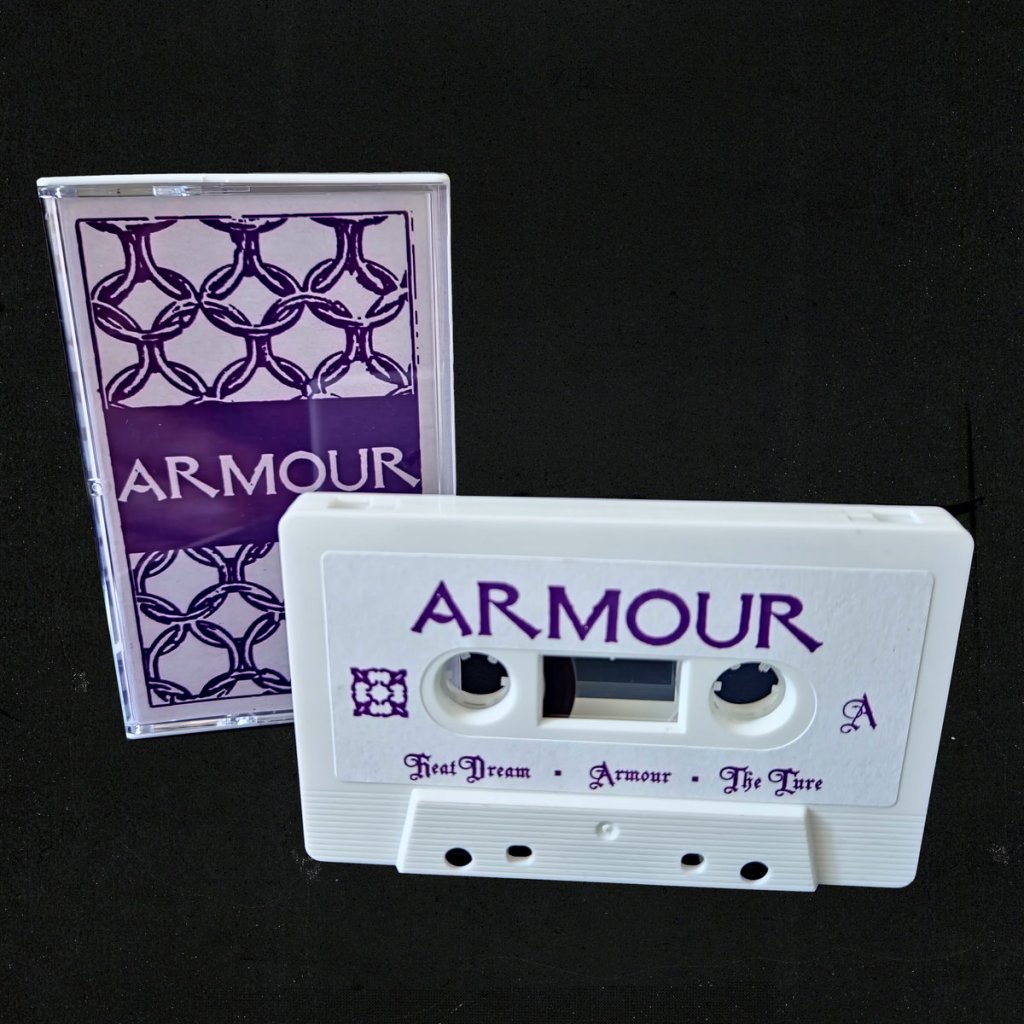

In this conversation, she reflects on loss, activism, and the ongoing evolution of both herself and her communities. Gimmie also dives into her musical journey, creative philosophy, progressive punk ethics, and the themes behind her projects—including her latest Naarm/Melbourne-based goth-rock post-punk band, Armour, as well as 100%, Bloodletter, and more.

LENA: You’re a really good writer!

GIMMIE: Thank you! I’ve been doing this for a long time—30 years, in fact. For a really long time, I didn’t believe I was even a writer. I doubted myself because I used to cop so much flack from people telling me I couldn’t write—mostly from guys in the scene. I was actually told that I should go back and pass high school English, along with so many other snarky comments that constantly put me down.

I used to get upset about it, but then one day, something changed for me. I realised: hey, I’m doing what I love, I’m having a lot of fun, I’m making these meaningful connections and doing work that means something to me. I feel like I have purpose.

LENA: There’s a couple of things I want to speak to there. I think you’ll just end up doing the thing that you want to do, regardless of what people tell you or say is the right way of doing something. If you feel good doing it, you’ll just keep on doing it or find a way to do it, because you feel bad when you’re not doing it.

You’ll feel like you’ll be doing it in some way—either professionally, in your own way, or by finding an outlet to do it, like a zine, writing a book, or whatever. Or you’ll just be having those conversations anyway. I’m speaking about you, but that’s the same for doing some sort of art, having a creative practice, or finding whatever your thing is.

If you’re a creative person or have some outlet, there’s always going to be people—especially when you’ve got some sort of marginalised experience—who tell you, ‘nah, the way that you’re doing it is not the way; it’s not my way.’

But if you do it from your heart, it doesn’t matter what the “right way” is. People are going to connect with it. If they connect with it, then it’s going to foster your own community and your own platform. That’s how you know it’s the right way, regardless of what the outlet ends up being.

Whether it’s through a zine, a book, a magazine, a piece of journalism, or even just using the radio or whatever, you’re obviously really good at drawing out conversation and stories from people. You have your own storytelling practice, and that’s really important. Like, fuck the correct writing conventions. People engage with how you tell stories, Bianca. It’s so cool.

Thank you. I just really care about the people I interview. I would never speak to someone whose work I didn’t find interesting or whose work I didn’t enjoy. My time is really limited because I do so many different things, so I have to just focus on what I really love.

I’ve been wanting to chat with you for ages—even as far back as when we saw you at Nag Nag Nag. I especially love your band Bloodletter and your earlier band, Tangle. It’s been really cool to see your evolution as a creative and how one thing informs the next. It’s the coolest thing to watch people grow.

LENA: Thank you. It’s really special that you mentioned Tangle, not my first band, but one of the first bands that played a lot and I got to do a bunch of things with. It’s nice that you can see the connection between what I was doing then and what I’m doing now. One of the privileges of staying in the creative arts community, like punk or any underground scene is seeing the beautiful ways that people change and grow, but become more and more themselves. That’s just an honour to grow up together in the different ways that we do.

In my experience of community, I’ve seen that sometimes people don’t want things to change—particularly in the punk and hardcore scenes. There’s that other side of things where, when people try to grow and evolve, others want to pull them back, saying, ‘Hey, no, but this is cool. Let’s just stay here.’

LENA: I’ve definitely felt that in many different ways, like with regards to style and genre. Especially in hardcore, there are very fixed ways of thinking. I have a respect for that in some regards, but also, I am not held down to any preconceptions that there’s a certain way to be—for me, at least.

It’s actually quite unhealthy for me to think that I have to be a certain way to be authentic or to be, like, quote-unquote, punk or whatever. That’s sort of the antithesis of how I relate to creative practice and the subculture that I’ve grown to love and be a part of. I wouldn’t want to hold anyone else back that way, but I understand why people sort of feel that way.

I feel it’s really important to hold things down in a particular way. But yeah, it’s a devil’s bargain of, yeah, these are the things that keep us safe and the logics of genre or punk, per se, or hardcore, while also it should be about letting people in and letting people be free to be their freaky selves as well.

I read an interview with you where you talked about growing up with punk and DIY. You mentioned that, in your youth, you noticed conflicts and approaches in hardcore and heavier music that were a little at odds with things in your life.

LENA: I have an interpretation of a punk ethic that is very progressive, very open, and about changing and supporting people to change while being accountable as well. There’s an openness to conflict in that sense, where conflict brings about disruption and change.

But there have been things that have happened in my life where people are very resistant to that kind of accountability—especially because of their own behaviour. These situations have been quite damaging within communities, and it’s severed ties due to the inability to communicate or because of what’s led up to some really poor choices. Yeah, violence and abuse within interpersonal relationships and smaller scenes in communities.

To me, that’s at odds with my personal ethics, which I drew from the people I had the privilege of hanging out with early on when I was coming into punk. That’s really informed my entire life. But I understand not everyone sees punk—or lives in the world—providing that kind of ethos.

And yet, not everyone has the same viewpoint as me, and that’s totally fine. I live in a community where folks don’t all have to agree. But, if you don’t agree with people, what do you do about that?

It seems like it’s getting harder to have these conversations, even just in everyday life, because everyone is so this way or that way. I’ve always thought that opening up a dialogue with someone is how you can actually start to affect change.

LENA: Totally. If you can’t talk about it, then you probably can’t do anything about it. A lot of people are afraid of being wrong because they think that means they have to change, or that they have to do something that means their way of thinking hasn’t been right. It’s too difficult for them. And that’s not just a punk thing. Every community suffers with that. It’s very nuanced. There are some really beautiful people in our community who are quite open to having these kinds of conversations. I’ve been inspired by them throughout my life. I call a lot of those people my very good friends.

Was punk scene the first community that you came to?

LENA: I grew up in a household where I had family around a lot of the time. There were a lot of folks who had migrated from the war, in a community with a lot of people who were struggling in different ways. I always lived around a lot of different kinds of people, and my community was always like family—extended family, neighbours.

There were a lot of interesting conversations about ageing and mental health that were normalised very early in my life because of my family’s mixed cultural background. We talked about trauma and death quite a lot, very early.

Those kinds of conversations meant that community was much more of a flexible idea to me: Who’s around you? What are you doing together? But also, what do you need from each other at that time?

I’ve got a really open idea about what community is, but I’ve never been the fixed-group, nuclear-family kind of girl. It’s always been more inclusive. I think that way of growing up has really imprinted on me, it’s a really special way to grow up.

You mentioned growing up where conversations about death were normalised. I know about a decade ago, you did a zine called Good Grief, and it explored grief and loss. I’m interested to talk about this; in the past few years I lost both of my parents. It’s been something that is on my mind a lot.

LENA: I’m sorry that you lost both your parents.

I’m sorry you’ve lost your dad too. My parents no longer being here is something that still feels really strange for me. I’m not sure if it will ever not feel that way.

LENA: That was basically the reason why my friend Erica [Newby] and I put that zine together. We both lost a parent within a couple of months of each other, and we found that no one except for each other got it. My friends were really beautiful at the time; they tried, but mostly, it was like, ‘If there’s anything I can do,’ or ‘I have no words.’ It was very much like, ‘You tell me,’ like, you do the work. Then I started getting a lot of ‘You’re so strong.’ I’ve been getting that my whole life—‘Look at you go, you’re so strong,’ and ‘You fucking kill it.’ And I’m just crumbling inside.

Same! I also get, ‘You’re always so positive!’ It’s like, yeah, but you don’t see me on my bad days when I’m in a ball, crying and feeling so low.

LENA: I feel like I recognise that about you in the few moments that we have seen each other.

I’ve experienced very deep sadness, depression and crippling anxiety in my life, and in those lowest, low times, I felt no one was there for me, I didn’t have any support despite knowing A LOT of people; obviously that’s changed having Jhonny in my life. But because of those experiences, though, I always try to be there for others and try to remain on the positive side of things. But it’s not always realistic.

LENA: Yeah. And it does damage trying to be like that a lot. I had a feeling that we were gonna talk about death and grief. It’s washed all over me—I’m a death girlie. [laughs]. I’ve always been a spooky little bitch!

[Laughter]

LENA: I guess I had lost people prior to my dad dying; I was 22. But no one so close to me like my dad was. My dad was my best friend. My friend Erica lost her mother to cancer, so it was two very different kinds of grief. My dad passed away very suddenly. I was on the phone to him one day, and two days later, he was dead. Heartbreaking.

Whereas Erica was anticipating the loss of her mother, and that’s also very tragic, as anyone who loses a parent or a loved one over a long illness knows. Both are bad. Especially at that age when you’re still coming to terms with yourself, and everyone around you is still quite young too. In Anglo-Queensland, where we were, people offered lots of prayers but weren’t really sure what to do. So we came up with the idea of doing the zine. We reached out to folks that we knew, and beyond, to submit whatever creative stuff they had about their experience of loss—about what it felt like. We wanted to share that with others so they could gain some insight into what grieving can be like, and to normalise those conversations a little bit at that stage in our lives.

I still have a copy of one of the masters of that zine I made, and I look at it every now and then. I’ve lost people since. We’ve already talked about change, and now we’re talking about death. The only constants in life are change and death. I’m continuously reminding myself of that. I talk about it with my staff. You just have to roll with that—change and death. Those are the constants in life. You can’t be afraid of it. The better you get at anticipating it, but not living in fear of it—living in spite of it and building your life around the choices you make despite these things being inevitabilities—you’ll make better choices.

But you’ve got to be able to support people in their fear of those things as well. Especially folks who aren’t brought up in a way or are unable to come to terms with talking about it. It is scary, and people run away from it. In the disability community, there’s a very close relationship between how people perceive disability and death. We’re living reminders of mortality, and that you don’t have all the strength you think you do. Something could happen to you, and the world isn’t built for that.

You recently won the National Disability Award for Excellence in Innovation.

LENA: My organisation did. I delivered a program through my organisation called Changing the Landscape, which provides resources on preventing violence against women with disabilities. The program targeted a national audience of practitioners in the disability service sector, as well as gender-based violence workers. These resources include videos, posters, and materials based on a 100-page document detailing the rates of violence and what can be done to stop it. They’re beautiful resources that I’m very proud of, especially considering I did a lot of that work just after a significant surgery. While I’m the program manager for that suite of resources, it took a lot of work on my part, but I’m just happy to have been part of such a dedicated team.

What motivated you to start working in that kind of space?

LENA: Gendered-violence or disability?

Both.

LENA: I have experiences of both. I had trained as a sociologist and did my honours thesis in urban sociology about gentrification—specifically, how people perceive their role in changing public space in a highly gentrified area known as West End. I was really interested in some things that didn’t end up getting discussed in the findings or didn’t emerge from the data. And that’s because I didn’t draw out a particular feminist analysis on the project, which was limited by the nature of an honours project.

So, I then just got into the swing of being a research assistant. But all the while, I was doing activist work on the side.

Before that, I had been doing activist work around gender-based violence, fundraising and learning how to mediate through grassroots organisations. I had been involved in this kind of work for a while.

After the publication of Good Grief, people started asking Erica and me if we were going to table the zine somewhere or if we were planning to do a distro. At the time, we had no intention of doing anything like that. We just wanted to create the zine and put it out there. But after people kept reaching out, asking us to do more, we realised there was a need in the zine space. We thought about what we would want to do, and we decided to start collecting and distributing zines written by women and queer people to sell at a market in West End.

We started doing that, and then I began incorporating records that were not just from cis men—bringing in women and non-binary people into the lineups. Eventually, Erica didn’t have the energy to keep going, so I continued on my own. Because of my priorities in the music scene, it ended up being a little more music-focused than zines, but I always maintained a bit of both.

This background relates to your question because, in doing all of this, I began booking shows here and there. The key was that there would never be an all-male band on the lineup. As a result, the shows I booked in Brisbane at the time had very creative lineups—something different from what was happening in the punk scene. At that time, it was mostly bands with the same members, and while they were really talented, the shows felt repetitive. Sometimes that’s cool, but when it’s the only type of show you can attend, it becomes limiting. I wanted to create something different.

Every other show I did would be a fundraiser for an organisation like Sisters Inside. I also started selling secondhand T-shirt runs to raise money for Sisters Inside. It became a part of what I was doing—some form of fundraising or activism, mediation, and being that girlie who always had something to say about what was going on and why certain things were such a problem. I became a little bit problematic but just stopped caring.

Going back to my time as a research assistant, after finishing my degree, I had no intention of working in the gender-based violence space. However, when a scholarship came up at RMIT University, it seemed to align perfectly with my skill set. They were looking for someone with experience in visual methods and a background in gender-based violence activism to research how young people engage with social media to prevent gender-based violence. I saw it as an opportunity to do something new, to align something I was already doing with my skillset, and to see what would happen. I had never really thought about doing a PhD, but it seemed like a good opportunity, especially since I was starting to feel burnt out being that girlie in Brisbane.

I had a lot of friends in Melbourne who knew what I was about and wouldn’t make me feel like I was alone. So it just felt like a good time to take the opportunity and run with it.

When I got to the end of my PhD, I was looking for work outside of academia because I don’t see the point in doing research if you can’t share the knowledge and apply it somewhere. I still feel like that. One of the roles that was coming up was at this organisation that I work for now, which is called Women with Disabilities Victoria.

To bring the conversation back to music, do you feel that each bands you’ve been a part of has represented different parts of your personal and musical development?

LENA: I wouldn’t say different parts because I don’t like to separate the self. Maybe at one point, I would have, but I’ve gone through a bunch of stuff in the last couple of years, and I’ve done a lot of deep reflection on everything—the shit, all the little things I’ve done. Definitely, in my younger years, other people would have asked, ‘How do you make sense of all this? You do this, and you do that, and you do this—how is it all the same?’ But in my mind, when I look at all that stuff, I see it as the same girl. I see the common thread. It all makes sense to me, and I can see where it can go.

Creatively, I’ve done a lot of stuff that might not connect together on paper, but it all informs one another. It’s always been about asking, ‘What else can I do? How else can I express myself? That sounds fun, or I haven’t done that before’. That was the thinking at the time—‘I haven’t done that before. That sounds fun. That’s a nice group of people, or an interesting group of people to work with. I would really like to try that. Let’s give it a go.’ And when it stops feeling like that, you let go of it.

There have been a couple of times when I’ve been super passionate about something, and you can probably tell when you’re listening to it. It’s like, ‘Oh, all those steps, all those little pieces I’ve put together, they’ve come into play.’ But it also goes back to an old band I did. It’s like, ‘Oh, she’s still doing that. She’s still thinking about that thing, and it still matters.’ That’s how I know it’s always been about finding the best way to express myself. It doesn’t matter the genre or the medium.

I had some downtime a couple of months ago, and I was drawing a lot. To me, my drawings are the same—they’re about the same things that I write my lyrics about.

You mentioned threads; what are they?

LENA:That’s something that I’m less open about. I’d like to hear what you think.

Thinking of your new band, Armour, even just in the name, there’s a really strong imagery to begin with. Armour feels like it’s both defensive and empowering. People go into battle wearing armour, so I was wondering if you’re exploring internal struggles or if it’s something larger and more outward?

LENA: Always, for sure. That’s always been a part of the ideas I’ve written about, throughout my practice as a creative person — as a poet, as a lyricist, as a writer. It’s stuff that I explore in my academic space as well.

I’m fascinated by struggle and change, and what people do to avoid it, or what people do when they are confronted. And that’s not necessarily a negative type of struggle or defence. It’s not something I’m always consciously aware of; it’s just something that I’m drawn to.

…I know that I’ve healed from some stuff I’ve gone through in my life because, working in the prevention of gender-based violence, for example, I see the long game. I can talk about violence all day, for example, because I know what the point is. And I see how to make change.

That’s why I’ve always been a somewhat confrontational person. But I know how to use those skills to get people, hopefully, going. I’ve got a good sense of humour to get people to think about things in a different way and bring them along for the ride, where it doesn’t have to be like this.

Part of why I really love your band 100% is because there is a lightness. I’ve read you say that the vibe of 100% is kind of like your aunt or Dolly Doctor. Any time I’m seen 100% live, it’s so joyful.

LENA: We have a cute little world that we created in that band. Like, it is what you imagine girlhood to be. And also, what maybe I do have nostalgia for. I did have moments of that typified girlhood with my friends when I was a teenager. But there’s the the dreaminess of that band— that was still, make-shift and put together through our own DIY lens, or in a futurist way of, like, what would the ideal be like? And what would we tell ourselves?

A lot of the lyrics were , okay, what would I want to hear if I was in this situation? And drawing from a few different situations that I did know about. Or if I was watching a movie, I’d think, what project would write the sweetest songs and charm each other through that? It was about supporting different aspects of songwriting between the three of us. None of us had ever done something like that before. It was really magical.

Yeah, well, it’s that— even though I really like the cover you put out that had the cake on it. That spoke to me in so many ways. One of my best friends made that cake too.

You mentioned a dreaminess, I feel Armour has a dreaminess, but a different kind of dreaminess.

LENA: Armour is the step between 100% and Bloodletter with a touch of Tangle. But in terms of tone, it’s definitely, at times soft sweetness. But also, I’m sweet, but, if you fuck up me or my family, I will fucking kill you vibes! [laughs]. That’s what being community minded is about, right?

[Laughter]. One of the songs I really love on the EP is ‘Heat Dream’. It has this surreal vibe.

LENA: What makes you say that?

Well, for one thing, the imagery, the fantasy and the dreaming in its lyrics.

LENA: There is a literalness of, like, I don’t do well in the heat [laughs]. It’s verbatim describing my experience of not doing well on a hot night. Knowing that others feel the same as well and taking it to the extreme. Growing up in the tropics, like in Brisbane, but also, like, there’s definitely being— like, is this fantasy? Am I awake right now? What was going on? What the fuck was that dream?

Your song ‘Sides of a Coin’ has a bit of a different tone to the others.

LENA: People are really engaging with that song. It’s really nice. I wrote the lyrics to that one really quickly. Those ones that just poured out. We weren’t sure whether or not we liked it as a band. So I tried to do something else with it. But I just kept going back to, this is how it has to be.

Lyrically it mentions about breaking the chains and setting yourself free, and there’s a sense of freedom from constraint. Maybe a feeling of liberation? You mention seeing the coin from the other side; what’s the significance of that?

LENA: I’m going to speak abstractly, because people will have their own interpretations. When I wrote that, I was thinking about the nature of truth.

I really like to write songs that engage with other songs, that sort of build a world. But that song, in itself, is a conversation. You see the coin from the other side—truth is subjective. There’s evidence, obviously. But if a rock fell between you and me, and someone who couldn’t see the rock asked us to describe it, how would we do so?

From your side, you might see the rock has some moss on it, some speckles, maybe a big crack from when it hit the ground. Thankfully, neither of us were hurt. From where I’m sitting, I can see that there’s light behind you, so you can notice details that I can’t. On my side, it’s the same rock, but all I see is grime. This rock is dirty. I mostly see the shadow of this rock right now.

We’re having a conversation about what we see, and to describe the rock, the arbitrator asks, ‘Are you sure you’re looking at the same rock?’

Yes, it’s the rock on this street, blah, blah, blah. So, what is the evidence? Are we going to fight about whose rock is the correct one? Do we get an opportunity to look at the other side of the rock? Or can we agree that on your side, it’s a nice green, sparkly rock with a crack, and on mine, it’s a funky, dark, grimy rock with webs?

It’s the same rock. And it’s a beautiful rock. And we’ve both survived.

Wouldn’t it be nice if everyone could be open to each other’s side of the rock?

LENA: Yeah, well, you don’t always get to that part of the conversation [laughs]. Sometimes you’re just like, can I just move the rock?

Do you see a narrative arc for the EP?

LENA: We just thought they sounded good in that order. Most of the songs were written at the same time. From my side, as the lyricist, they probably represent different aspects of things I was processing and responding to. I also added other bits in terms of lyrical content and other elements.

Was there a particular thing that comes to mind when you think about that period and what you were kind of writing to?

LENA: Something I really like about Armour is that it feels authentic as a band. I think there’s a lot in my part of it, which is about bringing people together—for healing, but also for a fight.

I was interested in the EP closer, ‘Last Train,’ because a last train could be a powerful metaphor for endings, choices, or opportunities. I also got a sense of exploring how distance or endings can bring clarity—or even healing.

LENA: That’s a really apt interpretation, without getting into the direct inspiration for that song itself. Each song has its initial influence, but if a song is conceptually strong enough, it will have a meaning that resonates with anyone’s experiences. And that was definitely something I was going for with ‘Last Train’: how do we move past an ending? What choices can we make? It’s about ownership of choice as well.

There’s a line in it that talks about breaking apart and yet making amends. Sometimes, those things can be in contradiction with each other.

LENA: A long time ago, in my early 20s, I came across the notion of creation and destruction, either in a zine or on someone’s bum patch or something like that. I spoke to it at the beginning of our chat—how, as a particular kind of troublemaker, I see change as good. But confrontation, too, can be a way to make change. It’s not the only way, of course, but I’m not afraid of conflict because it means things are moving. It can mean things are moving, as long as you know what to do with it. I try not to be too stuck in place.

That doesn’t mean I’m not stubborn. Things can hurt when you’re forced to do things outside of your control, but learning to let go is a big part of life. When you know things are ending, there’s a beauty in being open to what happens next.

I’m a big fan of saying no, so that you can rest and open yourself up for what the next yes is. I really respect when other people do that, even if it means they’ve said no to me [laughs].

I say no to a lot of things now. As Gimmie grows and so does my book and editing work, I get asked to do a lot of events, projects and stuff. I used to always say yes to everything because I felt I had to. But I’m a lot better at saying no now. I listened to this interview with a writer [Shonda Rhimes] and it really stuck with me. She talked about saying no to things without saying sorry or giving a million excuses for why you can’t do something. I used to feel bad for saying no, or people would get upset with me for not doing what they wanted or not meeting their expectations. I felt I had to apologise or explain myself. I felt bad for saying no. The writer shared that she simply replies: ‘No, I’m unavailable for that.’ And the first time I did that myself, I felt so good. That should be good enough.

LENA: It’s really respectable to know exactly where your limits are and hold up your boundaries, especially at the stage of life I’m at now. It’s a valuable thing to model for others. It’s scary how many people-pleasers I see, or how much people-pleasing behaviour I observe, where folks take on so much because they think, ‘Yeah, that’d be fun. That’d be cool. I gotta do it. Nobody else is gonna do it, or nobody else is going to do it the way I think it should be done.’

There’s a huge risk, not only in overloading yourself but also in not allowing someone else the opportunity to do it. Even if they do it a way you wouldn’t necessarily agree with, or do it differently from how you would, there’s a control aspect for some people. It’s also just a fear — the fear that if people recognise you now, they might forget that you exist later.

But there’s a beauty in being comfortable enough to say, ‘My time will come again.’

I love that! I think coming from the punk and hardcore community, something I’ve struggled with is allowing yourself to have success and actually celebrating that. I’ve always thought the mentality was weird — that when something becomes more popular, people stop liking it, even though the people creating it are still doing what they did with the same heart.

LENA: It’s not just the punk thing, but also the punk and tall poppy syndrome thing that comes with being in Australia. Like, ‘Oh, if it’s popular, it must be shit.’

But I’m talking about when it’s the same — or it’s probably even better than when they started.

LENA: Yeah, like ‘sellouts,’ all that shit. I understand sort of where that skepticism comes from. I goes back to what we were talking about with gatekeeping and of the purpose in small communities — why you would gatekeep, so that you keep your community safe. You want it to be special. You also don’t want yucky people or horrible people to come in and exploit what you worked so hard for or what was so important to you and gave your life meaning, to become like an open house necessarily. So, there’s a meaningfulness and care that goes into people saying, ‘No, no, no, no, no. It’s not for everyone. You go away.’

Lately, I’ve seen a lot of gross elements coming back into shows, stuff that was happening in the ‘90s and early ‘00s, there seems to be more violence and shit behaviour from crowds. Did you see what happened at Good Things festival on the weekend? In Brisbane there was lots of young girls reporting sexual assaults with older guys grabbing at them and not allowing them to exit the pit to safety. Also, people were crowd killing and going around punching people in the pit. Predictably, Good Things festival were deleting comments about it on their social media.

LENA: Something that I was thinking about when I was talking about, the ideal part of gatekeeping is that it keeps you safe, but the thing is, in my experience, a lot of the folks who end up doing that can also be the ‘yucky’ people — or they end up being the yucky people who have the loudest voices, saying, ‘This is what punk is.’ Like, ‘If you don’t like it, go back to the back of the room, don’t come into the mosh pit,’ and all this shit. And it does, regardless of how into being part of the mosh pit you are, or your perception of what’s a good time in a shabby mosh pit, and where the boundaries are, it does impact your engagement. Like, how ready am I to participate? Or when am I going to fuck off? Because, like, ‘Oh, that person’s there. This is no longer a fun time.’ Where, like, yeah, I can withstand a little bit of pushback. But like violence is different to what we recognise as like a mosh pit. For some people who come, there are some people who come to punk spaces or hardcore spaces because they’re attracted to being enabled to be violent.

They then — and this goes back to some folks having adopted a totally different ethos than what I found in my punk upbringing — and that’s on them, and that’s on me. But, you know, part of it is not being able to have conversations about, like, ‘Is that a way to treat another human being who’s also trying to have a good time? Can you recognise when you’ve crossed the line?’ And then bringing in other factors, like sexual assault and ableist behaviour. I’ve been at shows where folks using mobility aids are completely dehumanised, completely objectified, or treated as though they’re not even there. Or their wheelchair is just a piece of furniture that people can dump their bags on. That hurts my feelings — as an audience member, as a performer, as a member of the disability community — to see that folks in the audience, my peers, my community members, are not being recognised as human beings who are afforded the same right to enjoyment. For whatever reason, they’re either not actually being seen in the space, or where they are, the things that enable their participation are being used as, like, dumping grounds, just regular furniture for other folks. And it’s going to impact their freedom. It’s not good enough. It’s not right. But, folks just don’t think about everyone.

Exactly. That’s my point. I don’t think it’s asking too much of people to be thoughtful and mindful of other people in the same space. I’m tired of being told by bros that I’m too sensitive and punk rock is about violence and I should get out of the way so they can have fun.

LENA: You’re not too sensitive. You see everything and, yeah, I do too. Stuff that other people just don’t see. It would just take the smallest change, hey?

Yes! What are some things that never fail to make you smile? I saw you had a little gathering yesterday of friends.

LENA: Every end of year, my friends do a barbecue before everyone goes away for the holidays. My friends are really good at getting together and eating food. My friends are big eaters. We’re really good at doing nice things together.

I’m very motivated to find a thing that folks will like to do, like a movie or a thing that’s happening out in the regional areas, getting folks in a car together. Or going on a trip.

I love my friends. I’ve got the most beautiful people in my life. I’ve had some really tough things happen in the last couple of years. And it previously has been really hard for me, and it’s still really hard for me to ask for help, but they’ve shown the fuck up for me. That speaks to stuff that I’ve done for them and for community as well.

I can smile so hard, I cry when I think about the beauty of my friends, that I have the privilege of keeping in my life.

I love bringing people together. That’s a big reason why I like like to do music with other people. It brings people together in a beautiful way to think about what we have in common.

I saw in your Insta bio, that you said you’re: living deliciously. What’s that mean to you?

LENA: I really try to hold on to the good moments and make space, ‘cause my work is really hard. It’s really stressful. I’ve had a lot going on. I really try to make sure that I have delicious moments in my life and indulgent times, or even just me time. I strategically place me-time in my life, but also I have so much time for my friends. They’re beautiful, beautiful, beautiful.

I try to hold that up, and I don’t think it’s just only trying to look on the sunny side of life. It’s making sure everything is in balance. ‘Cause I can easily tell when the scales have shifted to the side of no, no, no, no, no. It’s about going the other way.

Before we wrap up, I’d like to talk about Bloodletter a little more.

LENA: Bloodletter was a band that I felt like, well, finally, I’m doing something that is the stuff that teenage me would be so proud of. I’m very proud of the recordings that we did. Fantastic group of people who liked music with some really heartbreaking songwriting. Some songs, every time we’d play them, I’d say, ‘Can we not play this song? It hurts my feelings.’

But I learned something every time I was a front person in a band. I learned how to work through that kind of thing—how much of myself to put into something—because I think it’s impossible for me not to put myself into it. But also, I learned how to work through it so it doesn’t feel like I’m bearing my soul every single time.

Jasmine [Dunn], who was in Bloodletter, played second guitar. She also plays in Armour. Moose is the main songwriter in Armour, and he had been sitting on five out of six of the songs on this current cassette for a few years. He’d demoed them and just been sitting on them. He’s a songwriting wunderkind, and we’ve been friends since maybe I was 20 or so. It’s a really lovely, long-standing friendship—he’s like a brother.

I was trying to figure out a solo project. I was teaching myself Ableton, which is still very hard. So, like, maybe in 20 years, there’ll be a solo project! [laughs]. But anyway, I sent him something I was tooling around with, and Moose said, ‘Lena, you need to be singing in a band. I’ve got some stuff I’ve been sitting on. Would you like to listen to it?’

I was like, ‘I’ve been waiting for you to tell me you had something. I’ve been waiting for a time where we were both available. Let’s do it.’ So he sent me five of the six songs that are on this tape in demo form, and I pretty much had two and a half of those songs written within a week. I broke away, and I was like, ‘I know exactly what to do. I’ve got stuff.’ It all just came out of me. I thought, ‘Perfect. This is gonna work out great.’

I knew exactly who to get as a second guitarist. When we got to that point, we filled out the band, and I thought, ‘Jasmine is someone I’ve always enjoyed working with in this kind of band.’ We had such a good time in Bloodletter together, and she lives in Melbourne now too. She’s so talented, as is everyone in Armour, so lovely to be in a room with.

That’s where that sound sort of comes in. Jasmine knows the tone, and she knows what I like. It’s very cheeky. Everyone in the band is very cheeky. They’ve got a good sense of humour, very chill, which makes it easy to be in that group.

With Bloodletter, you could lean into the horror, lean into the spooky stuff, while still talking about my lived experience. I really needed to do that band at that time. It was a good move away from having been in some ratty little punk and hardcore bands, which were great at the time, but Bloodletter was so different. Especially coming from Brisbane at that point in time, we were like, ‘Yeah, this is something else.’

Do you think that’s the band where you really started to find your voice?

LENA: I think so. I’ve always sung, but I definitely found my power in my voice at that time. I felt like I gained the most confidence through singing then. I was like, ‘No, I know this is what I have to do.’

And that connects to what we were talking about at the beginning. You go through all kinds of phases or times in your creative practice where people tell you the right way to do things, or what things need to sound like, or whatever. But if you trust yourself, you know.

This is the thing I always end up doing. This is the thing I’ve always done. I’ve got different ways of doing it. I’ve got my own way of doing it. But no one’s going to tell me how to use my voice.

Bloodletter in particular—and now in Armour as well—I don’t sound like anyone else. I trust the way that I sing. It’s not always in key, but it always sounds like me.

Follow: @armourmusicgroup + Armour bandcamp + 100% bandcamp + Bloodletter bandcamp.