Sitting down to chat with founding member of Poison Idea and legendary frontman Jerry A. Lang, I noticed that he’s softly spoken and super lovely. A surprising contrast from his loud, in-your-face, envelope pushing “Kings of Punk” hardcore band that we’ve all heard crazy stories about over their 30 year career.

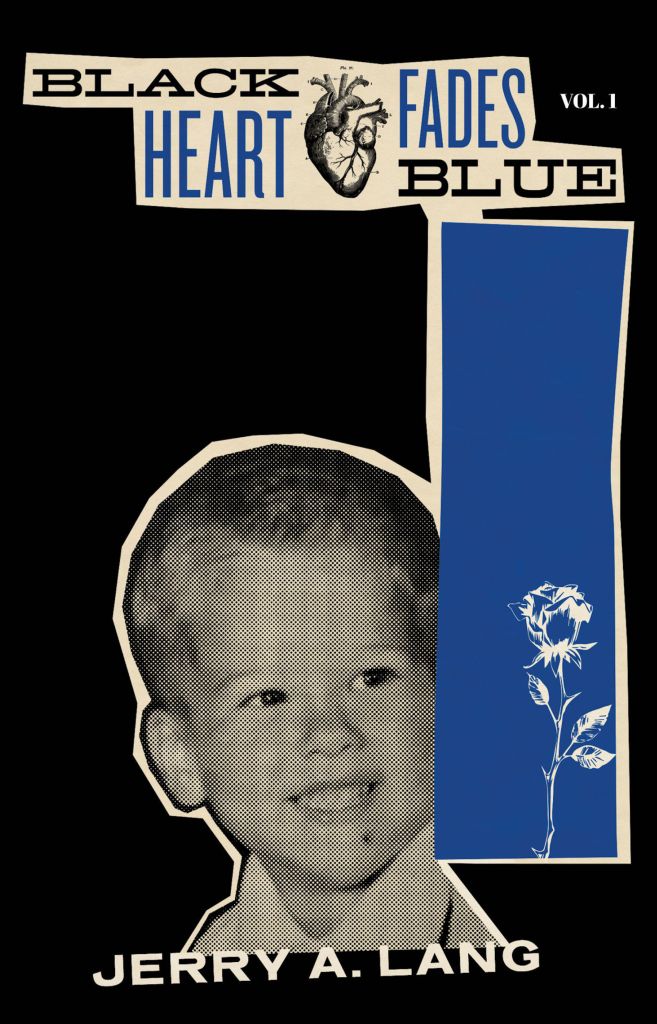

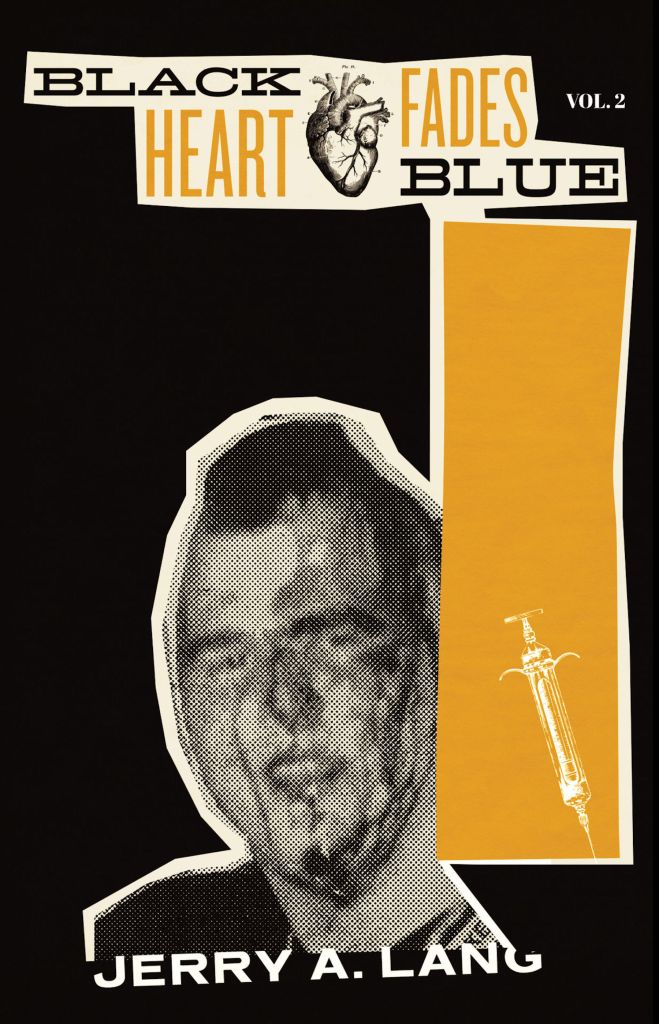

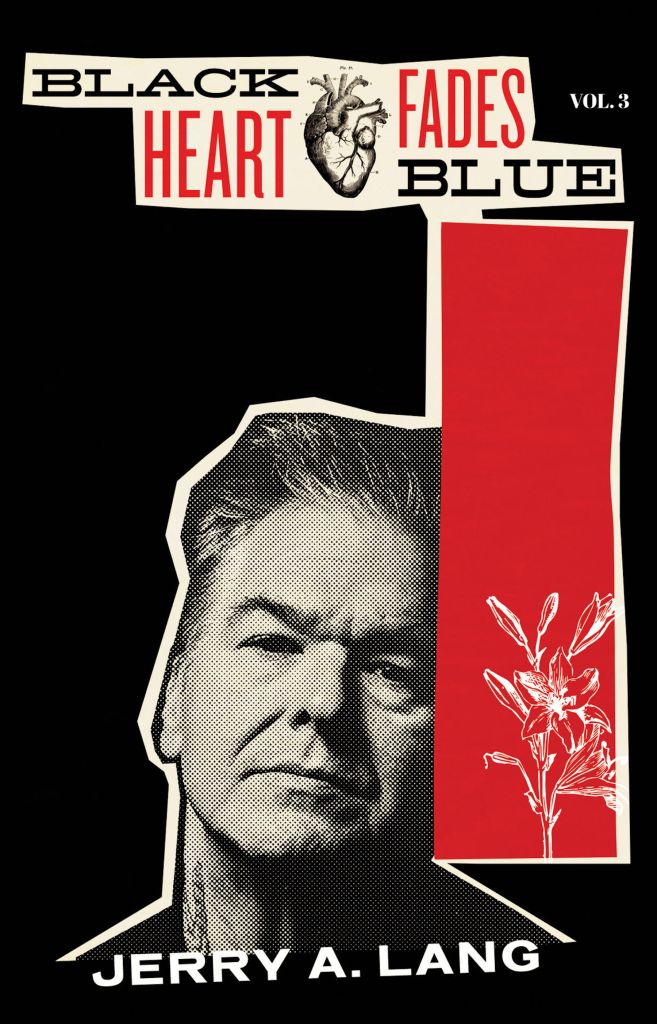

Last year, Jerry released a three-part memoir series Black Heart Fades Blue (which we highly recommend) that tell his intriguing, unconventional life story, the events that inspired his songs, and what made him stop hating and hurting. They’re a true reckoning of his past and present on the page.

Why is music important to you?

JERRY A: It seems like the easiest answer in the world, but it also seems like the hardest one. I don’t know why. Why do do children love their mother? Why do we breathe air? Why do we like sunshine? I had a great appreciation for art at a very young age. It’s just the music, it’s intoxicating. It’s like a drug. I was a little child and I heard it, and it was just magical.

In one of your books in your memoir series, Black Heart Fades Blue, you mentioned that when you were a kid, music seemed magic for you and that it made you believe that anything is possible.

J: It’s still that way. I hear some of the new stuff and I think it’s bad black magic, voodoo. These kids are throwing out some bad mojo. But I’m an old man, so that’s what people are going to think, damn you kids [laughs].

Can you remember the first piece of art that you experienced that had a really profound impact on you?

J: I was at a birthday party for a friend of mine when I was young, his older brother had Let It Bleed by The Rolling Stones. I remember looking at that album cover, just staring at it, and they were playing it. The record cover has a bicycle tyre, then a cake and then little figurines of the Rolling Stones. It’s stacked up. I remember looking at that and thinking it was so cool. I was probably three or four. I remember looking at it and going, wow, that’s amazing! I was mesmerised. That’s still a really cool record.

One of my favourite moments in your books is when you were talking about making art, all of your band’s flyers and album covers. It was cool to read about you making the logo for Poison Idea. How you had all these magazines and you used an X-ACTO knife to cut out letters, and how you turned a “B” into the “P”.

J: Yeah, you know what? It never left either. Me and my wife do art together, we try to make a weekly calendar. There’s some evenings where we’ll paint. I make collages and just stuff like that too. And it’s still as fun as it was then. It’s great. It’s actually working with some kind of magic bringing these things to life.

It makes me happy to hear that you still do art. I love that you still get excited about art and music after doing it for so long. I know so many people who get jaded.

J: Yeah. I’m on social media, I belong to this one group, it’s a bunch of old punk rock guys, a bunch of pissed off punk rock guys. They’re always taking the piss out of Amyl and the Sniffers and The Chats and bands like that. But these bands are saving punk rock. You don’t understand, you old bastards. They’re the new kids of punk rock. You guys just can’t accept it because you’re old and bitter. Australia’s always had just such great, amazing punk rock like The Saints, and it’s still coming.

I’ll make you a cassette mix tape of new Australian music!

J: I would love that. Thank you.

I love sharing music, that’s why we do our zine, Gimmie. It makes me so happy to be so stoked on someone’s music that I just want to share it with everyone!

J: Yeah, the mixtape thing in the 80s was such a really cool thing.

I used to make YouTube playlists for my wife when I was courting her. I would send her playlists with these punk rock love songs, and soul songs, and Al Green. How could you say no to something like that? [laughs].

Totally. The same thing happened with me and my husband. We lived in different cities and we started sending each other mixes of music, and art; that’s how we got to know each other. Then one day I was like, I’m moving to his city, he’s the coolest person I’ve ever known, I can’t not be near this person every day!

J: It’s like a movie, like, You’ve Got Mail or Sleepless in Seattle. But with a good soundtrack [laughs].

[Laughter]. Yes! I’ve heard you say that being a singer is the best job in the world; how so?

J: Well, it’s the best and the worst. Because I could kind of phone it in, call in sick or I could drink and do drugs during the job and that’s really not healthy to do any kind of job when you’re not up to standard. I got used to it.

You go on tour in Europe or wherever, and every city you play, the people are waiting for you. For them, it’s a big event. They’re waiting and they’re saving up all their party—they just blow out and have a giant party and go crazy. You’re thrown right in the middle of it. But the next day you have to do it again. The same exact thing, like Groundhog Day but in another city. So you you wake up and before you even open your eyes, you grab a beer and chug it to just try to take the drive to where you’re going to next. You do that for 50 days in a row, it’s going to do some wear and tear on you, but it makes you who you are. Hindsight is 20/20. But it can be a great job.

After writing the book and having people review it, I learned things that I didn’t know. It was pretty much a confessional. I listen to people’s podcasts and read stuff, people taking my songs and dissecting them. I was like, oh, that’s true. They say, it’s like a child screaming in anguish, it’s screaming in pain and throwing a fit, like firing on just the emotion. I never thought about that. I was like, hey, good call. And, besides maybe a politician, it’s the only job where you can get up there, scream and make a complete asshole of yourself. People agree with you or think you’re a complete asshole. I’ll put that on my job resume for future jobs [laughs].

[Laughter]. How does it feel different for you when you’re performing loaded to when you’re performing sober?

J: Well, I’ve only done it a couple of times sober, and I was obviously nervous. There’s a happy medium with everything. I’ve been doing this a long time, and I still have a couple of cocktails in the evening when I’m making art or playing my records or dancing or doing whatever, and there’s nothing wrong with it. I learned I should have done that earlier, just had a couple of cocktails. Everybody, most of the musicians and authors that I respect and all the good actors that I like, they would do that. But there’s parts where you abuse it. You shouldn’t go there. It’s not good.

Do you think having a couple of cocktails helps you relax?

J: Well, it’s just what I know, it’s just what I’ve always done. To try to say that I’m not going to do that, I’m going to do it like this, that’s like me going up and trying to sing in Spanish or Japanese. I don’t know Japanese and I can’t sing in Japanese. So that would be the same thing as going up there and singing without having any drinks tonight. I’ve never done that. I don’t know how to do it.

You mentioned you got nervous singing sober; have you gotten nervous before singing other times?

J: They say the chain is only as strong as its weakest link, I know that I can do my job, but there’s other people up there doing it with you. There’s the sound people, the instruments going out of tune, my band and the people at the club…It takes a perfect scenario for everything to go right. Things do tend to go wrong lots of times.

Sometimes I’m good to jump right in the middle of chaos and surf in it, I excel in that. But sometimes it’s hard, it’s like, your tyre flying off, as you’re driving down the street. You get a big rush of adrenaline, but sometimes it’s deadly.

The first time that you sang was at house party?

J: Yeah, a house party in Portland. It was all-star. There was a Portland punk band called the Neo Boys.

I love them!

J: I love them too. Pat [Baum] was playing drums and. K.T. [Kincaid] was playing bass, and people were up there, doing different songs. They were doing ‘I Want to Be Your Dog’ by The Stooges. I sang. It’s like riding a bike.

Before that you were playing bass in Smegma. When you decided to go from playing bass to being a frontman was it a conscious choice?

J: I was playing bass in a couple of different bands and it was fine. I really enjoyed it. But then I started seeing other bands and I didn’t think the singers were doing that great, I thought I could do better. They were really good musicians. I thought, wow, if I could do that, if I could get in that band with these people, then we could actually do something good. I made the effort to do it. It took a lot of tries.

In the Poison Idea Legacy Of Dysfunction documentary Mark Barr mentioned that you’re really a sensitive and mild-mannered guy. Would you agree?

J: I was just a kid, and I was taking everything in. I just kept my mouth shut, and I was watching everything happen and learning.

What’s something you remember learning that’s stuck with you?

J: I was a young child. I was a young man. There’s things you learn by yourself. I guess I pretty much confessed everything in the book.

Have you always been a sensitive person?

J: My wife seems to think so. Mark and I would watch the punks and the scene; the punk rock scene was very creative and very feminine-friendly. It was like a renaissance. But then the hardcore punk thing came in and like Tom [“Pig Champion” Roberts] said, it was an uglier music, it was a dumbing down. It was violent, it was mean and it embraced the nihilist stuff and all that crap. We were in it and we wanted to be the big band, so we wanted to be the kings of the nihilists. If you want to do that, you need to up your game. There was a time when I thought GG Allin didn’t have nothing on us. But honestly, who wants to fucking do that?

Totally. Previously you’ve said that you started Poison Idea when you were around 18, and at the time you were kind of having these feelings, of feeling unwanted and alone, and that’s what brought out the anger and made your art so intense.

J: It took me years and years to figure out why I did that stuff. Why all that, with everything, with the self-abuse and the drug abuse and the alcohol abuse and the abuse and the anger and the rage. Luckily, I married a therapist, a woman who’s actually, you know, kind of just tells me what what she sees. I was like, yeah, I guess you’re right. She’s an art therapist too.

That’s wonderful! Art can really help with healing and processing things. When I started reading your books, I actually read the last one first.

J: Oh, wow.

Yeah, I went backwards. Over the years, I’ve heard lots of full on stories about Poison Idea, and I was really interested to know where you were at now and what helped you change for the better? That’s why I read the last book first. You seem like you’re in such a happy space now. I feel like one of the biggest things that’s helped you is, love.

J: Yeah, definitely. You know, I was a drug addict for a long time, we all were in the band. Out of five people, two are dead and one’s completely M.I.A. – I have no idea where the other one is, and the other one’s just trying to survive. You come to a time in your life where you’re just like, I don’t want to do that anymore.

Now on the west coast of America, where I live, some drugs are decriminalised and you can be arrested or stopped on the street and nothing happens to you. There’s Fentanyl and stuff, it’s going to kill generations of people. Crime is going through the roof and businesses are closing down, and I don’t know what the end result is.

If I was a conspiracy theorist, I would say that somebody is wanting this whole society to be a society of masters and slaves. They’re letting us burn it down. So finally we just go, we’ve had enough. It’s like some fucking movie. It’s like Batman or Road Warrior. It’s so bad. I don’t know why people would want this. I don’t know why they’re letting this happen. They’re letting it happen, so it gets so fucking bad that we just go, please, do anything. Anything. Just make this stop. And then they’re going to say, okay, we will. No more of this, no more that, no drugs, no guns, no freedom, no anything. We’re going to say, yes. Just make it stop, please. It’s scary. There’s no such thing as moderation. It’s horrible. Lucky for me, I got sober. I can see it happening because I was there. I was in that life, I know how horrible it was.

Do you think with the times we’re living in, that maybe looking after yourself is more of an act of rebellion?

J: Sure. Yeah. I don’t think a lot of people are thinking about tomorrow. There’s a lot of people on a death kick. There’s a lot of people who are dying from drugs, like young kids. We had three kids die last week.

One of the things with punk rock, you were always taught to ask why about everything, to question everything— I’ve never stopped. I’m still questioning, why is this going on today? Why is this happening? Why are we letting this happen?

Like I say, there’s no moderation. There’s no grey area. It’s either black or white, and it’s really polarised. The whole world has been broken up into that side or this side. We keep fighting with each other, and we don’t really see what’s really going on. We focus on who’s the enemy because we know we’re right and this person is wrong. Maybe stand back sometimes and just look, the signs are everywhere.

It’s just about having awareness. There’s a lot of people out there that don’t even have awareness of themselves.

J: Yeah.

A lot of Poison Idea’s songs are based on things that have happened, personal experiences, and experiences of friends. What song do you consider to be your most personal that you’ve written?

J: Every song is personal. There’s a few where people would give me titles of songs, like my guitar player would say, here’s a song called ‘Hangover Heart Attack’ then I would write the lyrics around that thing.

Like I said in the book, I was with my friends in New York and they said, why don’t you write a song about rebellion? About the old rock and roll, getting in your car and driving off a cliff as fast as you can with your girlfriend thing? So that was it.

Two years ago, when we stopped playing, we did a series of shows because I wanted to come back and play good shows and then stop. And we did our second or third last show in Japan. I wanted to do a behind the stories type thing, where we played three songs, then I introduced a song and told the story about why I wrote it. So we chose Japan where they don’t speak English [laughs]. And I was up there explaining the songs to these crowds of people and they were just staring at me like, what are you talking about? A few people got my feeling; they were picking up on it. We said, this song’s about my friend dying, and this songs about my friend dying and this song I about my friend dying. There seems to be a theme here with our songs. They seem to be about people dying or people getting arrested or people having enough, or people being sad.

All the songs do have their little stories. Songs, they’re kind of like movies. Three-minute movies where you try to jam the whole thing in there so you can picture it in your head. I’ve never really thought about that before. So now I’m reflecting and thinking about that and going, wow, these are sad little movies.

There was a lot of losses of loved ones you wrote about in your books the one that really hit me and stood out was when your dog passed away. I feel like that really affected you.

J: Yeah. They were somebody that gave me unconditional love, my best friend.

My friend passed away about a week ago, I had a photo of him, and I saw the photo, and I thought that he really never left. As long as you keep someone in your heart and fondly remember them, you never really let them go, they’re never really going to die. Like Chris Bailey from The Saints. Because we’re all just energy and we’re all just stars anyway. So people never really left. We’ve always been here forever. It’s just how you look at things. I see some people walk around with black eyes, dead looks of not being there. Then there’s some people you just see and they just shine. I don’t think my friends are gone, the people that I love, I feel that they’re still here. I feel that they’re always there. We’re all stars. Wasn’t that like a stupid Moby song?

Yeah. ‘We Are All Stars’.

J: Oh, my god. I’m quoting Moby. I should stop [laughs].

[Laughter]. Speaking of stars, I noticed you have a copy of Van Gough’s Starry Night painting on the wall behind you.

J: Oh, yes. Right next to a Killing Joke poster, it’s from the Whisky a Go Go. Duality and balance!

Very cool! One of my favourite lyrics of yours has always been from the song ‘It’s an Action’: You can’t change the world, but you can change yourself. What inspired that lyric?

J: You know what? I wrote that thing when I was, like, 16 and I didn’t really honestly, at the time, I don’t think I believed it. I was just saying that. It’s one of these things, it’s like speaking in tongues. It just came out, and I had to eventually learn to understand what that meant.

Do you believe it now?

J: Of course. Definitely.

What’s the significance of the lyrics from your song ‘Feel The Darkness’ that inspired your book title Black Heart Fades Blue from: At midnight my heart’s fading blue?

J: That’s what black will fade to. It’s just the whole romantic symbolism of blue moon, blue hearts, and this horrific incident that was happening at midnight with this feel the darkness thing. It’s kind of like shining some light, getting some of that vitamin D, growing and opening up a little bit. It was an out of body thing. Sometimes things happen and it’s like you’re watching a movie and you don’t know why. You’re channelling it from somewhere or it’s all your experiences that are just coming through. Stream of consciousness.

When I was reading your books, it felt like they were written stream of consciousness.

J: That’s how we roll. A couple old friends who are reading it now and contacting me and asking me about it, I just tell them I kind of felt like I was caught for whatever I did. I was caught and convicted and I’m just confessing my crimes and I had nothing to lose anymore. I’m confessing everything. Saying all these things I kept for years. Confession is good for the soul. They say if you ever go into a jail cell you can see who the guilty person is, they’re the one who’s sleeping because he’s caught and he knows that, and it’s the other ones that are upset because they didn’t do anything. And so that’s how, I guess, I’m relaxing and sleeping because yeah, I did it [laughs].

Was it hard for you to face those things when writing?

J: Yeah. There were some things, stream of consciousness, as I was doing them, it flowed like water. But when I stopped and went back and read them, what I just wrote, then I would really shake and get upset. Sometimes it’d be very emotional because it was like, wow, where did that come from?

I’m so thankful that you shared your story, as I’m sure many other people are. I love learning through people’s stories, I think that’s why I’ve spent most of my life interviewing people. I love learning from others.

J: Yeah, it feels good. I can’t believe that people don’t continue to learn forever because there’s so much to know, so much to learn and it feels good.

You’ve been getting into to cooking and gardening lately!

J: Yeah! There’s so much out there. There’s so much in the world, it’s exciting and it just blows you away.

Find Poison Idea records at: americanleatherrecords.bigcartel.com

Find Jerry’s books at: rarebirdlit.com/black-heart-fades-blue-signed-by-jerry-a-lang/

Find Jerry’s solo album: jerryalang.bandcamp.com/album/from-the-fire-into-the-water