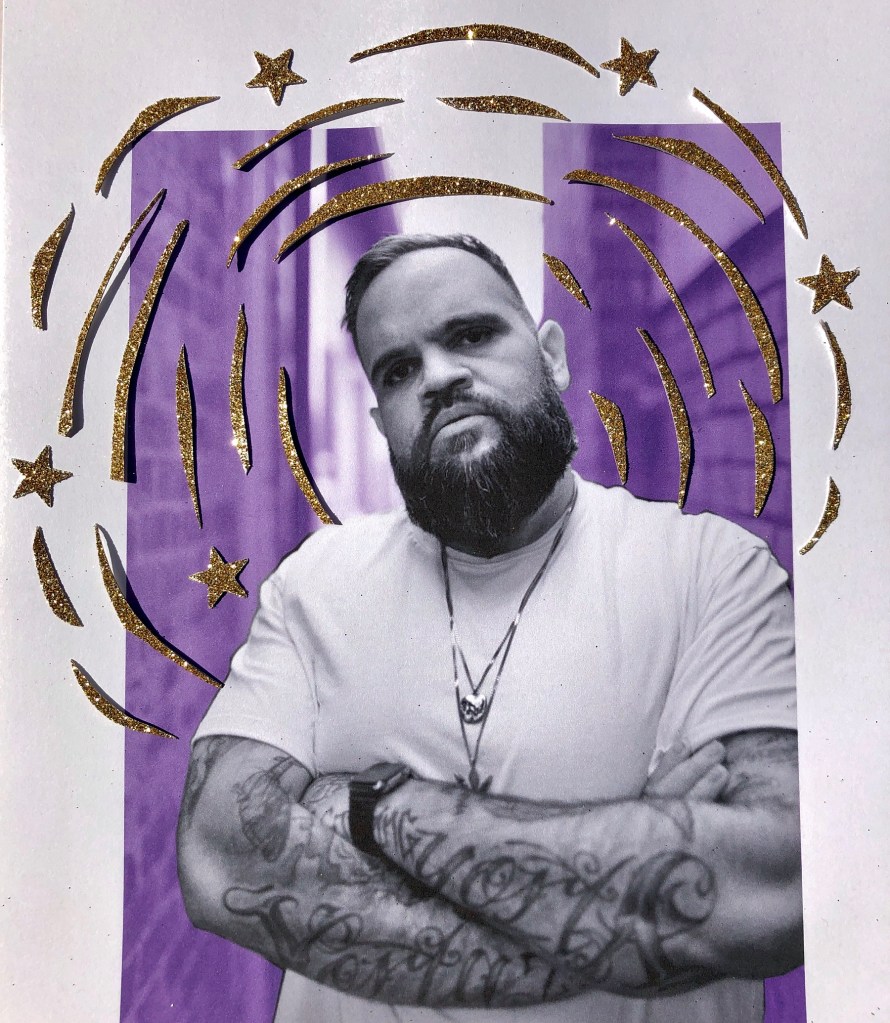

Trans adlay, Sidney Phillips, “the unofficial Queen of Australian Underground Rap” is incredibly likeable, hilarious and very, very real. Along with rap collective stealthyn00b, she’s part of the new vanguard in hip-hop. On Penance, her 2024 album, the Brisbane-based rapper sharpens both her sound and her sense of self. The beats hit harder, the writing feels more settled, and the themes come straight from her lived experience.

Across the record, Phillips reflects on identity, addiction, responsibility, and growing up on the internet. She’s candid about the consequences of drug use, the strange pressure that comes with having an audience, and the balance between honesty and influence. ‘You can do what you want,’ she says, ‘but there are always real-world consequences.’

In this interview, Sidney traces her path from early experiments with guitar and laptop beats to finding her voice in rap, talks about faith and community, and explains why staying true to herself—without glamorising or hiding the hard parts—has become central to her work.

Penance isn’t framed as redemption or reinvention. It captures change as it’s happening, with all its messiness intact.

This in-depth chat with Sidney took place just after Valentine’s Day last year. Since then, she has released album, Northside Dream.

Why is music important to you?

SIDNEY PHILLIPS: It’s my favourite thing in the whole world. I love art in general. My favourite thing to do is consuming art and making art. Music as a medium is the one that really speaks to me the most.

I love TV, and I love movies. I can watch one of my favourite movies, but I won’t want to watch it again for like a year, right? But with music, I’ll listen to my favourite artist every single day and I’ll never get sick of it.

Music is my way to relax, my way to have some fun, my way to express myself. Music’s given me so many great things in my life. All my closest mates I’ve probably met through music, and doing music stuff. It’s everything.

I totally get that. It’s the same for me too! I’m the kind of person who listens to a song and I’ll hear a part I like and I rewind straight away and I’ll listen to that part 10 times or something before I let the song progress. I just get so caught up on a sound, a melody, a lyric or something.

SP: Yeah, totally! It just sticks with me and sticks in my head.

Or sometimes I’ll be listening to a playlist and I’m loving the song I’m listening to but then I’m so excited to see what’s next on the playlist so I’ll skip through to the next song because I’m excited by the possibility of what’s next.

SP: Yeah, it’s always exciting. Love it. Seriously.

Your lyrics for song ‘2 Fucked Up’ mention that you were born in Carseldine not Morayfield; what were things like growing up for you?

SP: It was pretty chill. At least, Carseldine days. I was probably there until 2010, until I was seven. Memories of just chilling in the house and chilling with the neighbours—the neighbours’ kids—going to the shops with Mum and Dad. It’s all pretty good.

Both my parents are really switched-on individuals. Their childhood was probably a little bit different from mine, so they were thinking about, we’ll try and give the best go for our kids, sort of thing. So we had a really nice house, really nice area.

I went to a pretty nice school in the area. Things just got a bit expensive, so we had to move. But growing up was chill.

I think about it sometimes and how I got into the things that I got into. ’Cause it’s not like I had a super rough upbringing or anything, I’ll be dead set. But I still ended up getting into drugs and stuff.

The “I was born in Carseldine, I wasn’t born in Morayfield” line is funny to me. I was keen to put that in the song; it just came to my head, though, because I was thinking specifically about that. Are you guys from Brisbane or Sydney?

We’re actually based on the Gold Coast. But I grew up in Brisbane on the Southside. It always seemed like everyone on the Northside were weird and different to us Southsiders. It felt like a whole other world over where you are.

SP: [Laughs] Yeah, that’s that’s what Northside is thinking about the Southside too!

Carseldine it’s out of the city, probably about 20 minutes. But it’s still in a city and it’s not a not a super dero area. But ended up moving on to the more dero area of Morayfield. Not to hate on Morayfield, I love it here. I thought it’d be fun to just drop an honesty bomb. Like I wasn’t born here guys. I was born in Carseldine, which is a bit of a nicer suburb.

That’s one of the things I really love about your raps, you’re really honest.

SP: That’s what you gotta do. That’s what I love in my rap music, so I think it’s really important for me to try and cram as much personality and as much information about my life as I can. Give the listeners something to grab onto and be like, ‘Oh, that’s a bit interesting.’

Also, people can really relate to stuff. The amount of times I hear a song lyric and I’m like, ‘oh my God, that’s what I went through. That’s exactly how I feel.’

SP: Mmm-hmm totally. It’s good to hear you say that. That’s what I’m trying to do.

Before you got into music—’cause you weren’t really into music that much as a kid—you were more into video games. Then, around Grade 5, you got into Daft Punk and Skrillex—like, maybe when you were 10 or 11. And from there, it was Fall Out Boy and My Chemical Romance.

SP: Yeah [laughs]. Wow. I’ve never had anyone lay this all back to me! Makes me feel shy.

I think it’s always fascinating to know someone’s music journey. Then 13 to 15, you were getting into Bjork, Joy Division, Weezer, Radiohead, Godspeed You Black Emperor, which is pretty cool stuff for someone that age to be into. I know you have a really big love of the Beatles.

SP: Oh come on, we love the Beatles! LOVE the Beatles.

Totally! When did you start playing guitar? Was it before you started making beats?

SP: It was before. That’s a great question. Yeah, yeah, yeah—it was a guitar fest. Well, this is a bit embarrassing. Before the guitar, it was fucking ukulele. Because I always had one around the house since I was a kid. It’s like the kid guitar, right? I just picked it up. I wanted to start playing something, I guess.

I read a funny story on the internet about a guy learning a Metallica song on ukulele, and then there was a YouTube tutorial on how to play ‘Master of Puppets’ on ukulele. So I tried to learn that. And that was cool, because I was like, oh, this is fun—I’m playing an instrument and it sounds like something.

Then I started learning chords. And once you know ukulele—once you know one string instrument—you can go to another one pretty easily. I got ukulele lessons when I was in Grade 6.

That was my first musical expression. I’d learned some of my favourite songs on ukulele, and then from that, I started playing guitar—my mum’s guitar. It was a bit big for me at the time; I was twelve. So I’d be stretching out, trying to play it. I never got guitar lessons. It would be learning Nirvana riffs and shit like that. Totally dope.

I’ve always loved guitar music, but I’ve only ever had an acoustic guitar, so I wasn’t learning any Fall Out Boy songs or anything on it. It was more—shit, what did I even play back then? I got into Neutral Milk Hotel and play a lot of their stuff on guitar, ’cause it’s easy to play. But yeah—it was ukulele, guitar, and then making beats on the laptop.

When you started playing guitar, did you ever think, I want to have a band?

SP: Yeah, especially when I was really into Fall Out Boy, Panic! at the Disco, and all of that. Since I was a kid, if I’m interested in something, I’ll be like, oh, I’d love to do this as a job.

As a kid, I thought, I’d love to do something in video games as a job. But like—definitely not these days.

When I was like, oh, I’d love to be in a pop-punk band, I’d think, this would be the name, and I’d be the rhythm guitarist, or I’d be the lead singer. Stuff like that.

I never really tried to put it into action. I didn’t really know anybody who played instruments—or anyone who was really into the same sort of music at the time.

And even when I did think, oh, I’d love to be in a band, never in a million years would I have thought I’d end up doing something like stealthyn00b, and what we’re doing now!

You mentioned that you went from guitar to making laptop music and when you first started doing that, you were making instrumentals. What was it that got you into doing that style of music?

SP: Before it was the rap beat, I was trying to make vaporwave—which was the first thing I ever tried to make. I found vaporwave on the internet, and I was like, there’s something about it gripped me. I was like, this is so cool, so interesting. I loved the world-building in it.

For people who don’t know vaporwave, how would you describe it?

It’s an internet genre. It came out around the early 2010s. The basic idea is that its mostly samples—mostly ’80s—and it’s slowed down, chopped up, and screwed up. If you know about chopped and screwed music, like DJ Screw and that—it’s kind of similar to it.

It’s a lot about consumerist culture and ’80s nostalgia. I thought it was really cool because it’s a total sort of world—almost a digital world that you’re going into. And I love that in music, when there’s world-building.

I was trying to do that when I was eleven, and I was like, this has gotta be pretty easy—it’s just slowing down shit [laughs]. So I was doing that in Audacity, and I’d upload stuff to Bandcamp.

None of it was great—but it was something. I liked being able to make track titles and the album cover, make a project, and be like, oh, this is my EP.

With the beats, though—I decided to get into Kanye [West] and stuff like that. Kendrick [Lamar]. That was kind of my introduction to rap music, I guess.

They’re some of my fav rappers. I don’t like the stuff Kanye does to shock people and the massive ego etc. but especially his earlier albums I love. He’s good at telling stories and making beats. I LOVE Kendrick! The new album slaps.

SP: I still haven’t checked it out. I’ve been slow on Kendrick these days.

There’s a track on it ‘Man at the Garden’ that I’m obsessed with. And ‘Wacced Out Murals’ and ‘Squabble Up’. I love how he’s always so direct and honest in his rhymes.

SP: Yeah, I like that about Kendrick—he’s not gonna mince his words, and he does the whole rap game, I’m trying to be the best sort of thing. I fuck with that hard. I was late to his Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers album too.

Yeah, I didn’t get into that one so much either. I have all his other records but not that one.

SP: Yeah, that was the first one where I was like, I don’t know, Kendrick, I don’t know. Like, I usually love you, man, but I don’t know about this one.

Kanye and Kendrick were the first rappers I really LOVED loved. Before that, it was Eminem, N.W.A.—that was my first actual introduction to rap music.

I watched this guy on YouTube who’d make FL Studio tutorials, but they were also funny. He did: how to make vaporwave, how to make chillwave, how to make trap beats, and he did a how to make J Dilla / Nujabes-type beats. I watched that video and was like, oh, this sounds so good—the piano with the breakbeats, with the rain sound effect.

I was like, that’s it. I just realised how easy those sorts of beats were to make. At the time, I was just really keen on making something—being able to release something that was good—and being like, this is my music.

So I made a bunch of those beats, chucked them up on SoundCloud, chucked them up on Bandcamp—and that was my thing. My rap beat era [laughs].

Speaking of piano, I creeped on your SoundCloud and went back to the very first song that you uploaded. It was posted eight years ago and called ‘Last Night Changed It All’ and its got piano.

SP: [Laughs] That was the first rap beat I ever made!

Why did you call it ‘Last Night Changed It All’? Did something big happen?

SP: That was the name of the break—the sample. It’s from this 50s or 60s song called ‘Last Night Changed It All’. And that was what the breakbeat was called when I downloaded it. I was like, that’s pretty emo—I might just call the beat that. I thought that was cool. I still like that song I did. It’s got a pretty piano segment.

Did you rap on anything else before you created your own beats?

SP: In Year 7, I’d go over to my friend’s house and we’d get Audacity up and I’d chuck on some beats and we’d freestyle, not serious though. I was into rap but he wasn’t but we thought it was just fun to do. And it was! I still like making joke songs. I like rapping some silly stuff [laughs].

The first serious rap verse I ever did was in this internet collective when I was 13. A bunch of cunts I met on SoundCloud. We were a rap group called Immortal Diamonds [laughs]. It wasn’t me that chose the name, but I was one of the producers. I’d send beats but then I also hopped on a couple tracks for that tape. It’s still up on Bandcamp.

The first Sidney Phillips song I made was when I was 15. It’s on the first Sidney Phillips tape—it’s called ‘I’m Going Back to Sleep’. I made the beat, I rapped on it, and put it on SoundCloud.

When it came time to release the first Sidney Phillips album, I was like, I don’t like this vocal take anymore, so I re-recorded it. But that’s still on Bandcamp—and that’s the first Sidney Phillips song.

It sounds so different to what I make these days. It’s still fun to go back and hear the evolution. But yeah, it’s not really fun listening, though [laughs]. I don’t think it’s that good. Like, I was 15 making that.

Let’s chat about your evolution and releases.

SP: At the end of 2021—in September or October—I released the first Sidney Phillips tape. That was fun. It was all my beats and all my raps. I think there’s one feature on it.

It took me so long to finish—it’s only ten songs, and there are raps on eight of them. It’s stupid how long it took me to finish that album—like two years or something. And it wasn’t even that dope, either [laughs]. That’s the rough thing.

I was like, I want to make another album, but I don’t want it to just be the exact same. When I’m making a new tape, I’m always trying to think, what’s going to be different about this one compared to the last one? So it’s not just a rehash.

I decided, I’ll get other people’s beats on it. I made the first song, ‘Who’s Sidney?’ – I made the beat and then people started sending me beats. I was like, lad, I can make an album so much quicker if it’s just raps.

I can write the rap quick—it’s the beat that’s hard to make. You’ve got to find the right sample, find the right drums, it’s a little fucking annoying. I do like making beats, but that’s not the super fun part for me. The fun part’s writing.

I was in Year 12 writing that album, it was interesting. I went through some life changes. At the start of the year, I’d been dating this one girl for about three years; I also had my mates at school. Then, at the start of Year 12, me and my girlfriend broke up, and then my mates—“the leader” of my mates—decided I wasn’t cool anymore. So the rest of my mates didn’t want to be cool with me, besides maybe one or two of them.

Suddenly, I was pretty alone. I started going online a lot more because of that, and that led me to becoming close friends with twinlite and Love Lockdown. That ended up starting Stealthy Noobs. That’s a good ending to the story.

Dart’s got the original stealthyn00b members. It’s funny, because the three features that are on Dart were all members of stealthyn00b who aren’t in the group anymore.

I took it down off Spotify because, well, I’m not cool with everybody that worked on the album anymore. And also, there are a few songs that are a bit like… eh.

I even get that with Northside, the album that came out after Dart—six months later. There are still some lines where I’m like, oh, that’s really cringe, why did I say that? I wish I didn’t say that.

In what way are they cringe?

SP: I could have wrote it in a better way, in a cleverer way. I listened to ‘Doom’ off Northside, right? It’s like: I won’t go out like Doom / Sidney dies, unloved in their own room. That’s a bit cringe.

Was that how you were feeling that at the time?

SP: That was my raw emotion. I was trying to write what I thought a cool rap song should sound like, instead of just writing properly from the heart. There are some word choices I chucked in there because I thought they sounded cool at the time—not because it was really what I wanted to say.

What was the first song that you felt like you wrote from your heart?

SP: From the first album, I was writing from the heart. But some of it’s cringe because it’s like I’m reading a sixteen-year-old’s diary poetry, right? It’s a bit like, oh… this is pretty how-you’re-expressing-yourself [laughs].

Everyone starts somewhere. It’s so cool that you found an outlet to express yourself at that age. A lot of people go through their whole life and never find that. I love that you’re just really honest. ‘Cause a lot of people are posers. I remember reading an interview once with rapper 360 and he said the first album he ever got was Wu Tang, and I feel ilke he said it for cool posts and cred.

SP: Yeah, come on, man, you can you can be dead set! [laughs]. You can tell us that it was some cringe shit. It’s was probably the Spice Girls album lad! Yeah, nah, yeah, fucking 360 man. He’s a funny guy.

With the first album, I wasn’t really thinking about who was going to listen to it. So I was really writing it for myself. There’s some really like, are you okay, Sidney songs on the first album [laughs].

There’s songs like that on all your albums!

SP: Yeah, I guess so. Now I’m like, yeah, that was great that I wrote that. But maybe in five years, I’ll be like, oh, it was so cringe when I was 21! [laughs]. I was so emo. I was like, ugh. That’s my music, we like getting a bit emotional and a bit over emotional sometimes.

I really love the album title, To Live and Die on the Northside.

SP: Thank you. I was so proud of it. I was sitting around for ages, trying to think of a name. And then I was like, To Live and Die on the North Side. That’s it.

The same thing happened with Penance. Sometimes the album name comes straight away, and sometimes it’s like, fuck—what am I gonna call this album?

It reminded me of one of my friend’s bands, a punk band from New Jersey, Nightbirds. They had an album called Born to Die in Suburbia.

I know when I was a teen and living on Brisbane’s Southside in the suburbs it felt like that was hat life was like, like, it’s so boring here and I’m just gonna die here. It was a bleak feeling.

SP: Yeah. It does get pretty boring in suburbia. That’s a nice thing about being an adult. I can leave when I want to. Like, let’s go! I can stay up! But it’s cool to keep a kid vibe too. I’m gonna be like a kid forever. I’ll always be excited about stuff like that.

Another great album title of yours is, I’m so Tired of Being Staunchly.

SP: Thank you. So, I’m still in high school, and I’ve got all my friend issues. It’s about being lonely, a lot—a bit of, like, fuck everybody! [laughs].

And then Northside is a bit more of the same. For a bit of background context, I met another girl. We started dating, and then while I start writing staunchly—me and that girl break up, and then…

I’m getting a bit of a pattern here…

SP: [Laughs] Yeah, it’s always breakup albums. High emotions, really. When your emotions are high, you can write really well.

What else was going on?

SP: There were dramas with the group. We had to kick a member out and that was really tough, because we still really loved them. But, they couldn’t be in the group anymore.

Back to 2022, I met this guy from Sydney through Instagram who works in the music business and he was helping me out—trying to sort the group out and trying to get our shit out there. There was me and the guy we kicked out—we were gonna do an EP together. And my manager guy was really keen on pushing it to everybody. It felt like we were going up, and then… it was really fucking frustrating… it was a defeated time in the history of Stealthy. I felt pretty down.

Was that when you started getting into benzos? Because you were feeling depressed. Maybe you were trying to numb yourself to cope? I know eventually you got to a point where the benzos weren’t helping anymore.

SP: Yeah, that’s it. It’s just bad. They make it all worse. Like I said, I had so much friend drama and girl drama and fucking shit for two years straight. It seemed that it just kept happening over and over and over again. Like, I’d make some mates—

Oh my fucking family group chat is buzzing. Oh, shut up. Sorry. I’ll try and figure out how to turn that off. Oh my gosh.

It’s nice you have a family group chat! That’s really sweet.

SP: [Laughs] …But anyways, I’d make some great mates and then something happens and we can’t be friends anymore. It felt like a lot of people were just fucking me off. I felt discarded by a lot of people.

Before I got into benzos, I’d already had some friends who did Xanax. And growing up, you hear about Xanax—you’re like, oh, Lil Peep died from Xanax, you know, and so-and-so died from Xanax. I’m like, wow, Xanax is a bad drug.

But I’d go to my mate’s place, and he’s just on Xanax. And he’s rapping like crazy. He’s so sociable. And I’m like, well, why is this guy on Xanax and functioning great? I’m like, Xanax can’t be that bad.

My girlfriend at the time was like, ‘You’re not doing pills!’ I was like, okay, I won’t do pills. But then we broke up, and I was like, man, fuck everything—I’m gonna do some pills, bro. I don’t care anymore. That’s kind of where it got to.

Writing Staunchly—it was a sad time, but it was also an empowering time too. Because when stuff goes bad, bouncing back can be a really powerful feeling.

I started being really close friends with my mate Skratcha from stealthyn00b. And he put me onto so much cool Chicago music, drill, and Aussie rap as well. We’d hang out, do drugs, listen to Aussie rap, and be like, bro, fucking Australian music is so good! [laughs]. Like, it is the best.

Xanax made me feel tough. It made me feel cool at the time. But then getting off the Xanax—it was hard, obviously.

Staunchly, is one of your releases that has the most attitude. It was like you were trying to tell the world that you’re tough. It’s like you had something to prove.

SP: Yeah. It’s the first album where I was talking about gender stuff too, and where I’m speeding up, and singing. It’s funny because on the other albums, I’m trying to sound tough too but the thing is, I’m not that tough really [laughs].

If you’re listening to rap music because you want to hear a tough guy, Sidney Phillips isn’t the person to listen to, man, right? You’re better off listening to Flowz or Kerser.

Why was it important to you to rap about gender?

SP: It was really important! I was always too scared to. Then one of our friends told us they were trans as well. And she’d rap about being non-binary and shit and keep it staunch. Old mate was so, adlay—like, low-key, just like me—and so gay at the same time. And I was like, I’m never rapping about gender stuff, ’cause that’s cringe. Like, when you’re listening to rap music, you don’t want to hear about gender stuff.

But then I hear that, and I’m like, what the fuck—this is so cool. Because you’re getting to know who they are as a person and what they believe in. And, that’s cool.

I was like, I fuck with this so hard. It doesn’t have to be one or the other. You can infuse your rap with who you are, even if it’s a bit scary, even if you think it’s a bit embarrassing.

Sometimes being trans—especially someone that looks like me—can feel embarrassing, you know? But you’ve got to be honest. You’ve got to be honest with the world. I am trans. So there’s no point, being embarrassed about it. Might as well rap about it, you know?

And it gives trans people listening something to connect to. And that was what it was like for me, hearing my friend rap about being trans. I was like, this is so empowering. This makes me feel cool for being trans, but also loving my gangster shit.

’Cause it’s pretty niche. I don’t know a lot of people like me—but there are people like me. I’ve gotten DMs from fans being like: I love my adlay shit, but I feel embarrassed to tell my friends I’m non-binary, or whatever.

I want to help people be themselves and not feel embarrassed.

I love that! In my experience, the hip-hop space I grew up in was very a homophobic and misogynist world. Do you feel things are changing?

SP: Totally. I think so. A social change.

The music we make—the music people make in general—is getting more and more progressive. There’ll always be some misogynistic rap, and there’ll always be homophobic rappers. But I think socially, as we get less and less okay with those bad things, it slowly—but not surely—goes away.

Twenty years ago, there wouldn’t have been a Sidney Phillips. There wouldn’t have been a trans rapper rapping about doing adlay shit.

The fact that stealthyn00b exists, the fact that there are trans rappers out—it just shows progress. It shows where we’re moving forward as a society: being more and more okay with things that aren’t traditional.

Like, fifty years ago, shit was so much different. So in fifty years from now, I hope everything will be a lot more accepting and progressive.

Your latest album is, Penance, obviously the word penance has religious connotations: repenting for your sins. The album’s themes revolve around addition and coming out the other side. You’ve been to rehab a couple of times; can we talk about that?

SP: Yeah. It was like an outpatient detox thing, so it wasn’t technically rehab—it was a detox thing.

Just before Staunchly came out, I went to detox for the first time ’cause I wanted to quit Xanax and all that, but I was having trouble quitting on my own. I’d be off it, and then I’d relapse.

Detox was helpful for me—talking to the drug counsellors. I had so many one-hour sessions, chatting it out with the counsellor, about everything to do with my drug use. Having those ideas drilled into my head was probably really important.

Drugs really change the way your brain is wired. Your thought processes aren’t working properly, and they’re making you do stupid things [laughs]. I needed that to be sorted out.

After detox, I was back into making music. I still had a bit of trouble quitting after that—there were a few relapses here and there—but they get fewer and further between, as time goes on.

Where you still feeling lonely at that time?

SP: Sometimes I was by myself and sometimes with friends. One of the things that I needed to change for me was, hanging out with people when I know that they have pills. I know me and I know if I’m with someone and they have pills, I’m going to want to do it, as much as I know that doing it is bad. So if I knew my friends had pills, I knew not to hang out. It was rough, but I had to do what I had to do. I was sad because some of those people were really good mates.

On the album, in song ‘2 Fucked Up’ you talk about all that.

SP: Fuckin’ oath!

There’s a line in the song where you say: There’s nobody’s helping me.

SP: Yeah. [Raps] I feel like nobody’s helping me, please somebody help me / I been taking all my meds but ain’t nothing helping.

A bit of context about ‘2 Fucked Up’… I went to detox the second time, right? About a year after the first time because I wasn’t taking pills anymore, but I was just, broke but still buying weed every week, still smoking every day, and drinking every night. I was spending any money I had on substances—which isn’t good.So I needed to go to detox again to get off everything, at least for a while, so I could get my money back, right?

I probably took a good six weeks off weed and drinking. And wrote ‘2 Fucked Up’ during that period. I wrote ‘Get Rich…’ during that period too.

I got my money sorted out now, so I drink and smoke sometimes. But I’m not in debt to anybody and I’m not a broke cunt anymore [laughs]. I know that I can smoke weed and still go to work and still like live a normal life. I stay away from the pills these days though—it’s bad news.

I’m stoked for you. A lot of people don’t really see prescription drugs as drugs, or being that harmful but they’re a lot worse than weed or mushrooms, you know, natural shit.

SP: Yeah, the doctor can prescribe people a benzo for anything. It’s not as big of a problem here as it is in America. In America, you tell the doctor you have anxiety and you get a prescription for Xanax twice a day. It’s so fucked up. I could talk about benzos all day. I have so many thoughts on them. I did have my fun on them but I wouldn’t recommend it to anybody.

On song ‘Get Rich or Die Tryin’ there’s a line you spit about not wanting to encourage your fans to do pills. When did you first realise that your words can have power to other people?

SP: It was the weirdest, weirdest thing. I’d been making music for a long time at that point, and I’d never really had an audience until Staunchly.

Around the time Haunted Mound had come to Australia, they were on Twitter being like, bring us Rikodeine to the shows. And I thought that was kind of rough, right? Because a lot of their fans are teenagers—all-ages kids. So a lot of these fifteen-year-olds are probably looking up “what is Rikodeine?” for the first time.

I rap about Rikodeine—or at least my older stuff did. Not really anymore. I don’t rap about it anymore because I don’t do it anymore. And in the stealthyn00b Discord, there was this kid… he’d bought the same Nautica jacket I had. He got his haircut the same way. And then he posted, like, I just bought some Riko—there was a photo of the bottle of Rikodeine he bought from the pharmacy.

He was, sixteen!

I was like, bro… I was like, that’s not cool. You shouldn’t have got that.

And he would’ve only really known about it through either Haunted Mound or me. And I felt so guilty in that moment. I was like, oh, this is fucked up. I was just like, bro, don’t do that shit. Chuck it out. And he was like, I just took one sip. I already feel something.

And I was like, bro—don’t do that shit. Chuck that shit out, man! You’re stressing me out.

When I started rapping about Xanax, doing a song called ‘5 A4’s in My Nikes’, I put that out, and then I put on my stories: just letting you know, we don’t support drugs, and we don’t want anybody taking pills. And someone replied to me: yeah, it’s all good to say you don’t support it but you’re still supporting it if you’re rapping about it. You’ve gotta stop talking about it. And I was like… man. Maybe I should stop talking about it. Maybe I do have a duty to my fans to not be promoting these negative ways of living. On the other hand, I shouldn’t be censoring myself. I’m an artist. I should be able to write about what I want to write about. You can do what you want but there are always real-world consequences.

First track on Penance ‘Lead Horse to Water’ is about seeing your friends in the midst of addiction and you want to help them but you can’t really help people that don’t want to be helped.

SP: Yeah, it’s real. I wanted to change what I’m rapping about, but it kind of just happened naturally, as my opinions on things changed and as I lived a bit of life, and I saw the effects of what living that sort of way does to people.

Instead of rapping about, pouring Riko in my lemonade on the train, I’m talking about trying to help out my homie but he won’t fucking listen. It’s rough because that’s real.

There are two sides to the coin. Drug use is really fun [laughs] when you’re doing it but it’s really painful as well, for the person and for the people around them.

I find drugs really interesting. I consume a lot of media related to drugs, It’s sort of poetic and heartbreaking and shit. I don’t want to just show the fun part.

You don’t want to glamorise it?

SP: Yeah, I’m just dead set in that, This is the life that my friends live, and that I live to an extent, but I’m not gonna sugarcoat it and say that it’s all mad fun.

As someone who’s been through addiction and seen friends struggle with it too, is there anything you think someone going through it now could do to help themselves? Or something you wish someone had done to help you?

SP: The advice I’d give to someone that’s in that situation, trying to help a friend out, is you want to try and be patient. You’ve got to be as patient as you can be. Because, drugs just fuck with a person’s brain. Most drug users want to quit, right? Most bad drug users want to quit, but they feel like they can’t.

You can talk to someone and they’ll be like, yeah, I’m so keen on quitting. I’m fucking sick of it all. And they can pinpoint exactly why the drug is so bad for their life and be like, yeah, fuck it, I’m not doing that shit anymore. And then, like, two days later, you see them and they’re back on it. It can get so frustrating. So that’s why it’s important to have a lot of patience and to try and put yourself in their shoes as much as you can.

That’s the most difficult thing for someone that’s never used. Someone that hasn’t been there can be like, it’s so stupid. Don’t they see how destructive they’re being? Don’t they see how they’re fucking up everything? They do see it. Of course they see it. But the drugs have such a fucking grip on them. They feel like they can’t let go. Like they can’t get out of it. It’s too scary, it’s too hard.

Patience and kindness is the best thing you can do when someone is in a bad place and hurting. Try not to give up, too. It can get really frustrating but don’t give up!

When I was doing Xannies, I probably had someone give me the Xannie talk, like, ten times before it really sunk in. Remind your friends that what they’re doing is fucking stupid! [laughs].

The other part of it too is, that people forget when you take pills, your body becomes addicted to it. And when you’re ready to stop, you physically can’t, because your body craves it. And you’ll do anything that will take that pain away, that detox, and that really uneasy, gross feeling you get when you finally want to stop.

SP: Yeah, yeah. Exactly. Because that’s the easier thing to do. And that’s why it’s called an addiction. You can be ready to quit, but your body isn’t ready.

I remember it was the worst. I thought having another Xanax would cure me. I’ve never been dope sick or anything but that’s probably the closest thing I could compare it to.

I could be with my friends. I could have weed. I could have alcohol. I could have my girlfriend. But I could still just be wanting to kill myself, you know. Just being like, fuck, more than anything I just want to go out and get Xannies. That’s so ill, right? It’s such a mentally ill way of thinking but that’s just what the drugs do to you.

You have a song called ‘Cuts On My Wrists’; how close to home is that song:?

SP: Yeah, a little. Self-harm was never the thing that I dealt with when I was a younger teenager. It happened around the benzo-years, I started getting into that. I was in a dark space and feeling like I needed control.

Sometimes, I guess, it’s a way to feel, though, too, because you’re so numbed out from all the benzos. Like, I just want to feel something again. It’s like, can I still even feel something?

SP: It’s kind of TMI but I did it on the benzos because they make you so impulsive. I have a song ‘I Want To Hurt Myself’…I’d be at my mate Skratcha’s place and I’d want to hurt myself. We’d be chilling in the kitchen and just cut myself. Why? I don’t know, I wanted to. It’s pretty random. That’s not something I struggle with anymore.

Thank fuck! I’m proud of you.

SP: Thank you.

You’ve done a lot in a short period of time. In my opinion it’s the best thing you’ve ever done.

SP: Oh, that means a lot! I reckon it is probably the best thing I’ve done.

The production’s gotten real pretty.

SP: Thank you! Making it, I was so worried. Like, oh, I hope people like this as much as the last one. I hope people like this more than the last one. Because the last one was so obviously my best work at that point. It was easy to make an album better than Dart. It’s easy to make an album better than Northside. But it’s not easy to make an album better than Staunchly for me, at this point.

I love the variation and the different emotions. And the way your flow has evolved.

SP: I like to think so. Thank you.

Your laptop died while making Penance, right? You were like 70% finished when it happened?

SP: Yeah. More then half of it was from 2023. My laptop died around Christmas and I didn’t have the money to buy a new one because I was so broke. I didn’t get a new laptop until I went to detox again, four months later.

Did you remake the songs you lost?

SP: No, I’d saved the files. We got all the files off my laptop. The laptop itself died, the CPU completely fucked it, but we managed to recover everything, so I didn’t have to remake the album, thank goodness.

I actually made this album on two laptops. One was the laptop I made Staunchly on, and that one’s dead now. I couldn’t get into the project files on it, though.I had the finished songs, but I couldn’t go back and edit them.

When I was working on ‘Make It Back’ – the original version was from mid-2023, but I needed to extend it so I could get Ricky’s verse on it. That meant finding the beat again and re-recording the whole song. That’s one track that’s re-recorded.

When my laptop was broken, I was making songs on my phone using BandLab. There were also one or two BandLab songs that I later recorded on the laptop as well. So there were a couple of re-records, but they didn’t end up on the album. I think they’ll go on the deluxe edition.

Is there a song on the album that you’re really proud of?

SP: I’m really proud of all of them [laughs]. I’m really proud of ‘2 Fucked Up’ because it’s so catchy and emo and ridiculous and funny. It’s all my favourite parts of my music in one song.

‘All My Friends Are Leaving Brisbane’ is another song I’m really proud of, that stuff had been on my mind. It’s good to be able to sum up my feelings in a song.

Do you feel kind of lonely or isolated sometimes because a lot of your crew left for Melbourne or Sydney and you’re still here?

SP: Yeah, yeah. I had two close friends move from Brisbane to Melbourne and one of my other friends that lived in Adelaide moved to Melbourne too. They were all kicking back. And suddenly, people don’t have as much time to like talk on the phone and shit like that,’cause they’re living their fun life and I’m living the boring life here in Brisbane.

I like your line where you’re talking about your friends being in Sydney, but you hope they don’t forget Sidney. That’s kind of a real Kanye like line.

SP: Yeah, I love putting your own name in the lyrics. I’ve always loved that. I feel like it’s a specifically rap thing, talking about yourself. In other genres, they’re not really doing that. They might be singing about themselves but it’s usually in a more poetic way. I love how raw rap is, just being dead set. Saying what you really feel.

Do you know how many times you say the word cunt on your new album?

SP: Oh-no, did you count?

Sure did!

SP: [Laughs].

88 times.

SP: What!? 88 times? I’m going to do 100 next time!

[Laughter] On ‘2 fucked Up’ you say it 15 times.

SP: [Laughs] Of course! There’s a few clean songs on Penance, which were an accident. I noticed when I was going through a looking at what songs were explicit and which songs weren’t.

Yeah, there’s seven songs that you don’t swear in.

SP: [Laughs] That’s gag. It’s crazy. Ridiculous. It’s awesome. There’ll be 100 c-words on the deluxe.

[Laughter] You grew up Christian; is the album title Penance inspired by that? Also, you eventually did your own exploration of Christianity and decided you kind of didn’t believe in God for a few years, when you’re around 13. And eventually you went back on the path.

SP: Yeah. I thought about it all for a while, like, oh nah, this shit doesn’t sound right. I did my own research into it. I get such a strong feeling in like my heart when I hear gospel music. It makes me cry sometimes, l feel overwhelmed with emotion. The religious stuff is pretty real for me these days.

You thanked God in your album liner notes.

SP: All praise be. I’ve done a physical release for every album I’ve made, and every one has a note thanking God. I always thank my friends, my family, and God, you got to, he’s number one, he’s making it happen [laughs]. I always thank God. On ‘Act Famous’ it says: [raps] Coming up quick but it wasn’t up to me / All the thanks is to my God that’s right above of me.

I’m not really interested in making gospel music but I’ll chuck a lyric or two about God in there, just because that’s me.

I remember when I first heard Kanye West’s song ‘Jesus Walks’ and thinking that’s a really powerful song. It moves you, whether you believe in God or not.

SP: Mmm-hmm, yeah. For me, that’s why it’s so amazing. It’s like, wow! That’s heavy. [Raps] God, show me the way because the Devil’s tryna break me down… I wanna talk to God but I’m afraid ’cause we ain’t spoke in so long. Ohhhhhhhh! That’s hard. That gives me goosebumps.

I got into Kanye when I wasn’t really Christian anymore and then I heard ‘Jesus Walks’. Fuck, those lyrics really hit: I’m just tryna say the way school need teachers / The way Kathie Lee needed Regis, that’s the way I need Jesus. Ahhhhh! I LOVE that!

What are the things that are important to you about creativity?

SP: It’s important to be yourself, always, to be unique. Everybody’s art exists because of everybody else’s art, right? You can’t ignore your influences but you don’t want to lean too hard into your influences either, because then it’s just not cool, right? The thing with clone artists, there’s lots of clones of each other, right? With rap especially but it’s like, why would you want to listen to a clone?

I’ve noticed there’s a bunch of artists out their now that try to emulate and bite your style.

SP: [Laughs] There is bro! [laughs]. It’s fucked up, it’s very weird. The first time I heard someone sounding like me, I was like, fuck off cunt! This is not right. Why would you want to listen to the clone when you can listen to the original? Why would you want to get the Aldi-brand when you could get the real Coke.

It’s not only the hip-hip scene, it happens in the punk scene too, one day everyone started sounding like Blink-182 or Bad Religion or Ramones or whatever. I never understood artists that straight rip off someone else’s sound. Push things forward, put your own spin on it. I can hear some of your influences in earlier stuff but I think you’ve found your own thing now.

SP: Yeah. That’s what you need to do when you’re making art, you need to take your influences, put your own spin on it. If I’m out at a show and I hear a band that sounds like Blink-182. That’s pretty disappointing. But its different when you hear a band sounds a little like Blink-182 but they’re doing their own thing. I fuck with that. You have to do it your way.

Did you see that guy on Instagram reels the other day? This guy blowing up doing a Sidney Phillips type thing and everybody was flaming him in the comments [laughs]. It’s so funny, man.

[Laughter]. One of your clips ‘Effy’ has around 20,000 views, which is really cool. And on Spotify, it had 128K+ streams.

SP: Yeah, it’s so good!

Totally! Gimmie has a YouTube where we’ve posted 100s of live vids we shoot. Recently one got 2.2 million views [it’s now at 3.6 million!] of a local band, Guppy. It’s funny how we had that vid go viral and we get crazy numbers in views on our interviews, yet all the other media and publicity people in Australia don’t think our little publication matters.

SP: Wow! I haven’t had a I haven’t had a video go crazy like that.

Why do you think people latched onto ‘Effy’?

SP: I post a TikTok of a snippet of every video that I do. The TikTok gfor ‘Effy’ got some decent views, like 14,000. Suddenly, we got a bunch of comments. That was the first big one. It all kind of happened from there, when it did well I started getting booked for shows. I’m pretty happy with where I am now. But I’d love to not have to do my day job anymore.

Where do you work?

SP: Woolies [laughs]. In the deli, mostly. Its’ not terrible. I like the actual job. It’s annoying being understaffed, though.

I saw footage of a recent show you played in Melbourne and it looked crazy! So much fun! It was a packed house and everyone was just losing it. It must be a bit of a head fuck to go from from playing awesome shows then going back to Woolworths?

SP: A little bit. Definitely, after doing the show. The recent ones in Sydney and this one in Melbourne, blew everything else out of the water. I’d never done a show with more than 150 people. The Sydney show was 300+. The Melbourne show was even more; packed with everyone singing along.

It looked like you were having the time of your life! Your vibe, the crowds vibe, it was pretty special. Watching that, you get the feeling that you won’t be playing in small rooms for much longer.

SP: Sometimes I’ll tell my coworkers about stuff. They’ve known me for three years now, and they know I’ve been doing music the whole time. It’s nice to be able to be like, oh, guess how much I made off this show, or guess how many people came to this one.

But yeah, for the most recent one, I had to be like, bro, I’ll show you my bank account, right? I promise I’m not lying. And they’re like, no, no, I believe you, I believe you [laughs]. It doesn’t sound real sometimes, though.

But IT IS real. You’re living it! And people are really responding positively to your latest album. I am so excited to see what you do next, Sidney! I’ve secretly been hoping you’ll incorporate more of the emo and post-punk influences.

SP: Yeah, come on, come on—we’ll get all Joy Division-y with it.

Follow @sidneyphillipz + @stealthyn00b & check out sidneyphillips.bandcamp.com