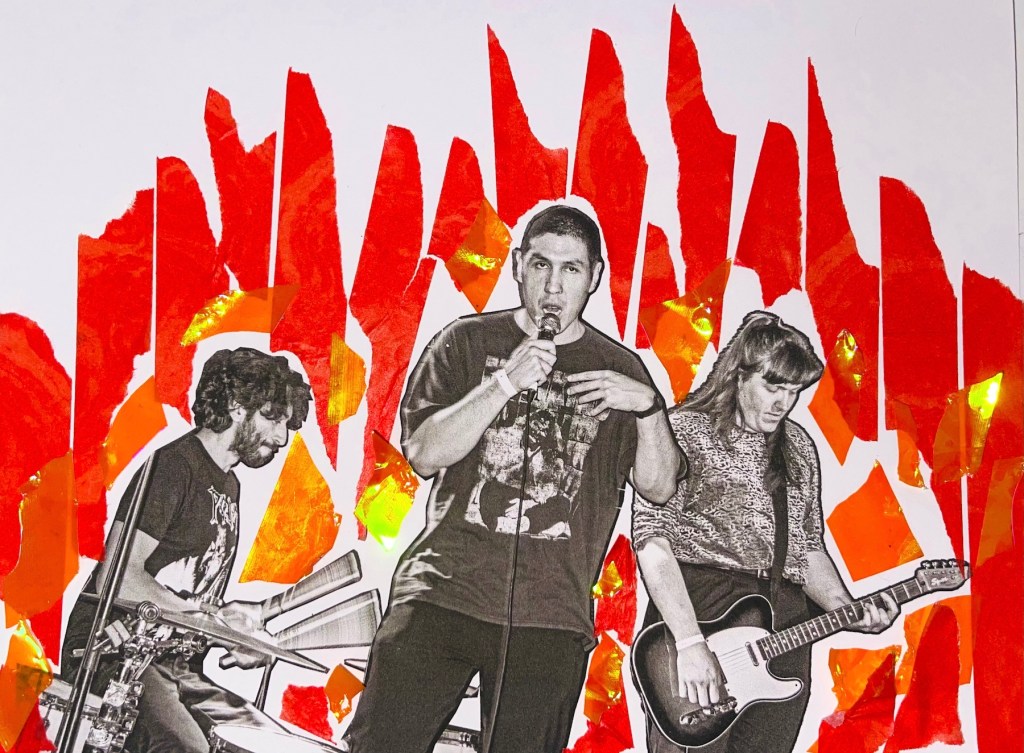

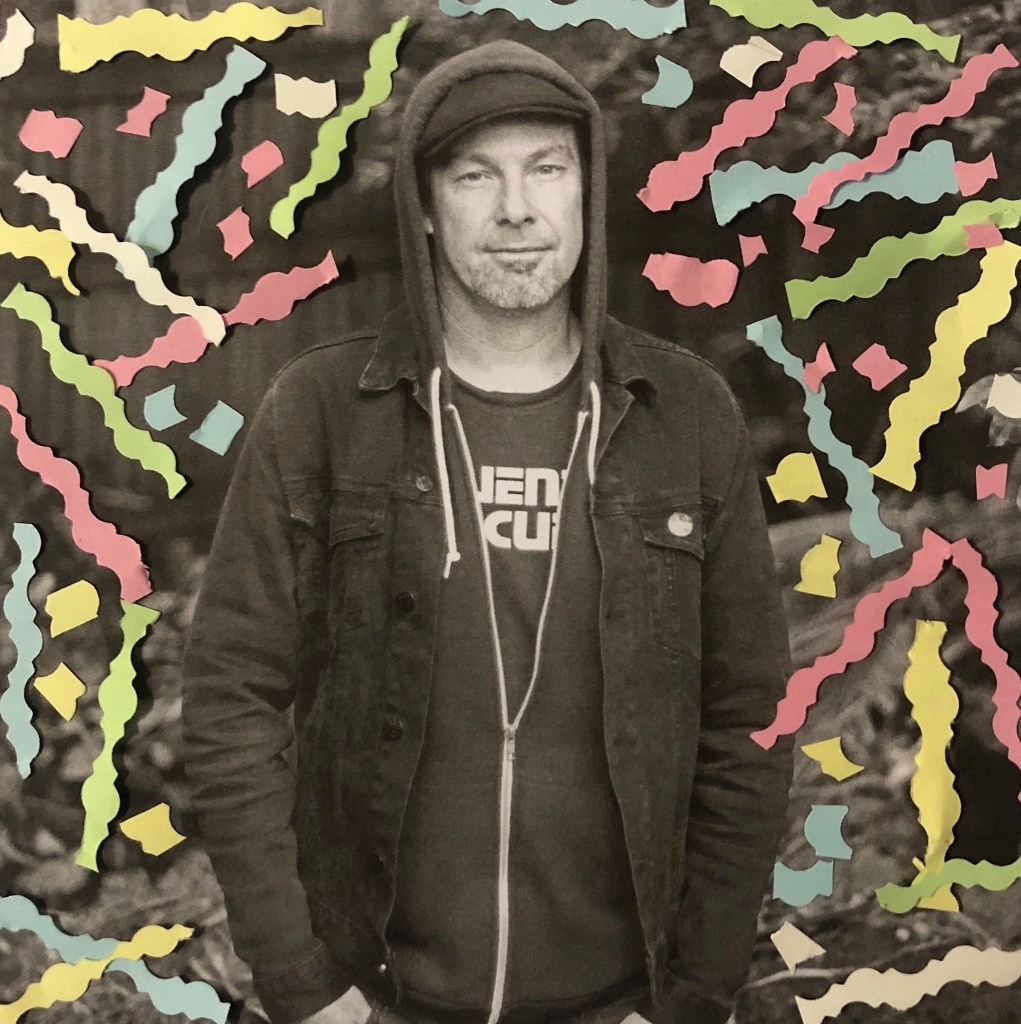

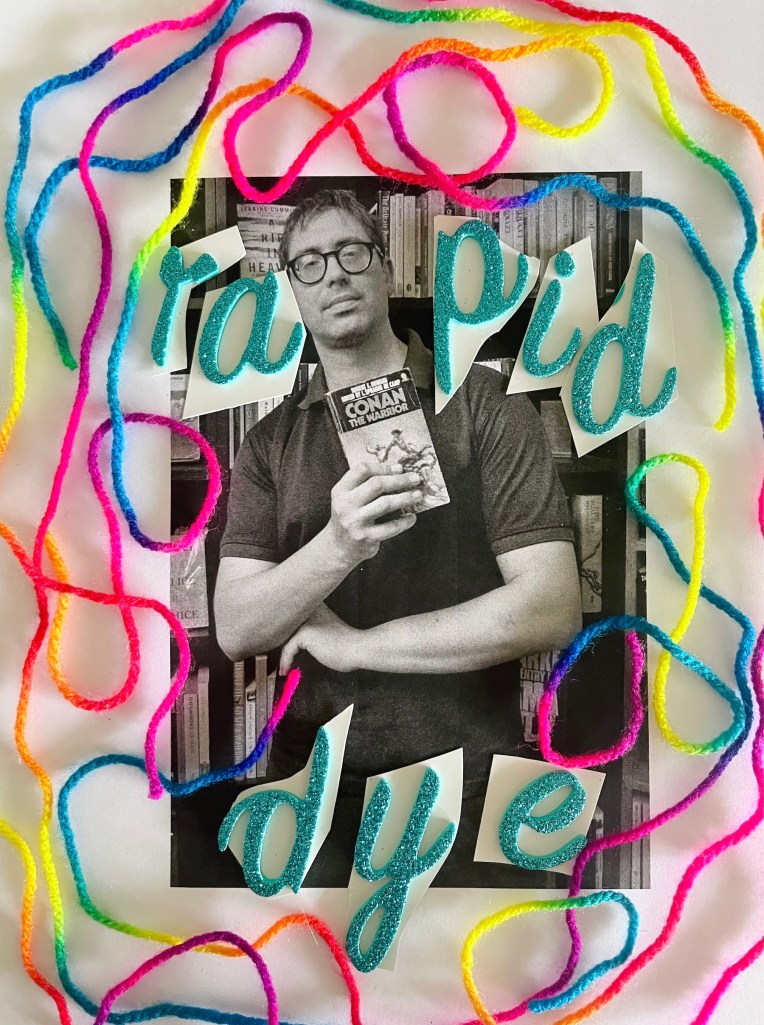

Sydney band, Rapid Dye, gifted the world THE Australian hardcore record of the year way back on Valentine’s Day. It’s a record built for the floor, for the crowd, for the pure energy of classic hardcore done right. It hits hard and lingers long. They’re one of the savagest hardcore bands around. IYKYK.

Gimmie caught up with Josh Ward, Rapid Dye’s vocalist, to talk about the record, his journey to making music and a record label, Sexy Romance. We also talk about the most hectic things that have ever happened to him that might just make your jaw drop.

What was the first kind of music that really hit you?

JOSH WARD: Around 14 or 15, I started listening to Metallica for the first time. That was such an eye-opener, because when I was young I used to listen to Silverchair and System of a Down, and I started really, really liking that stuff. Then I got turned onto metal and became an absolute metalhead, listening to the top bands. I remember reading magazines saying: you have to listen to the Big Four — Metallica, Megadeth, Anthrax, Slayer. From there, it just snowballed. I was like, alright, this is what I want to chase — that heavy sound.

I’m glad you’re honest about what you first got into, because some people I talk to tend to namecheck bands they think will make ‘em sound cool, not who they were genuinely into. Like, they don’t wanna sound like a dag.

JW: [Laughs]. I grew up in Logan, Queensland, and the closest I could go anywhere was about a 20-minute walk. Buses only ran every two hours to the main town. So pretty much, I had to learn from whatever I found at the libraries in Beenleigh, just whatever CDs they had. The libraries had racks of CDs. I’d be like, ‘Oh, Metallica — that’s cool, I’ll put that aside. Oh, Rage Against the Machine — that looks kind of punk.’ I remember there was D.R.I., a real thrashy album and I used to think, ‘Oh, this is kind of cool.’But back then I wasn’t really that into it; I just had an awareness that a more funky kind of sound existed.

I got into D.R.I. early because my older brother picked up their Crossover record when it came out in ’87. He also got me into Dead Kennedys and Suicidal Tendencies. Was there a moment for you when you really realised punk and hardcore were your thing?

JW: Yeah, I was 15. I remember it so clearly because I really liked this girl — she told me she was playing in a band called Not Negotiable, kind of an emo band. She was in it with her boyfriend. I liked it because she went to the same school, and she said, “Oh, you should come to the show.”

So I went to the show at Eagleby Community Hall. There were a couple of other bands, one was this big hardcore band called Time Has Come. I started listening and thought, ‘Wow, this is incredible — I’ve never heard anything like this before.’

It was the first time I’d seen people moshing. I think this was around 2005, so everyone was wearing camo pants and big straight-edge shirts [laughs]. And I just thought, straight away, ‘I can’t believe this — this is incredible.’

Cool! I remember going to the army surplus store in the city and getting camo pants and cutting them into long shorts.

[Laughter]

JW: Yeah. As soon as that show finished, I’d forgotten I’d even gone because I liked her — I’d just enjoyed the show so much. I really wanted to support her and I talked to her, but more than anything I couldn’t believe there was this whole scene. No one from my school went but I knew some of the older kids from other schools, and gradually I started talking to them.

Before Rapid Dye, were you involved in any other bands or projects?

JW: I moved down to Sydney in 2012. Before that, I was trying to start hardcore bands, but nothing ever really eventuated — not even a first show. I used to practise, pretty much driven by this feeling that I really wanted to join a band, but I never had the opportunity to jump in because no one was ever sick.

Then I started this Quadrophenia-worship band called, Little Mind. I used to dress all mod for it. That was when I was pretending I didn’t really like hardcore — you know, that angsty 19–20-year-old phase where you’re like, ‘Oh, I’m over hardcore now, I’ll try to be a bit more hipster, a bit more in that scene.’ I did that for a little while and really enjoyed it, but deep down I still wanted to do a hardcore band. I just couldn’t get enough momentum to make it happen in Brisbane or on the Gold Coast. So I decided it was time to move.

I tried moving to Melbourne in 2012, but I only lasted about a month — I didn’t like it at all. I was going to a few shows, trying to meet new people, but it couldn’t click. I don’t know if it was them or me, but it didn’t work. Then, on a whim, I decided to try Sydney. I didn’t want to go back to the Gold Coast, and a lot of my family was in Sydney, so I thought, ‘Let’s just see how it goes.’

On the very first night, I met one of my best mates now, Drew Bennett from Oily Boys, at a pub. We were sitting at separate tables and started talking — I think because I was wearing a hardcore shirt. From there, I knew I wanted to stay in Sydney. Twelve months in, and I was still here.

Nice! How good is Oily Boys’ album, Cro Memory Grin?

JW: Incredible! Hardcore doesn’t have to be done in a certain way — it can be done differently but still stay within that realm of hardcore. I consider them a hardcore band, but I can talk to people and some would tell me, ‘Oh, they’re more punky or almost more experimental than anything.’ To me, they’re, at their core, pure hardcore.

Totally! I really love Drew’s latest band too, Chrome Cell Torture. Being on the Gold Coast we’ve gotten to see them play a bunch. Every single time has been awesome.

JW: I’m really happy for him that he made the move up there, because he’s now really focused on what he wants to do. He sends me messages all the time with lyrics he’s written, all the new songs, and he’s like, ‘Recording the album!’ I’m really looking forward to seeing how it all goes for him.

Same! Did you always sort of want to be a front person?

JW: I think I did want to be a frontman. Especially when I was living in Queensland. I didn’t feel like I was cool enough a lot of the time though. I picked up the bass so I could try and squeeze my way in somewhere. But that was small thinking — I thought I didn’t have the tools to do it.

That changed a lot when I moved to Sydney, because I think at that point my brain was switching to, ‘Let’s try and make something. I want to be a part of this scene as much as I can.’ That’s when I started the label Sexy Romance in 2013. I was like, ‘Well, I’ve got this job at an architecture firm — I really shouldn’t be here.’ But I managed to squeeze my resume through, and they were happy to pay me. I thought, ‘Alright, let’s use this extra cash to put out records.’

At that time, a lot of hardcore felt a bit stale. None of it really hit that edge — it was a bit lowbrow, but also didn’t feel genuine enough. So I decided, ‘Alright, I’m going to stick with this label, see how much I can do, hopefully connect with some people, and then start a band.’ I figured if anyone wanted to start a band here, I could put out the record. That’s how my brain was processing how I could get into a band.

That’s a lot of work to be in a band!

JW: Yeah, I was just thinking… anything that would help me be able to try. Deep down, this was my way to prove to myself that I’m really into this. That I really want to be somebody. Or… I feel like I’m giving back to the scene that gave me so much — that actually gave me an identity; who I really wanted to be.

I get that. When I first started getting into punk and hardcore, I was like, how can I be a part of this? No one would start a band with me — because I’m a girl. Back then things were really bro-y. So I started doing zines, which I’ve been doing now for almost 30 years.

JW: I spent some time this past week reading your interviews, and I haven’t gotten this much out of a zine in a long time. A lot of the zines I usually read feel like the people being interviewed are used as a stepping stone for the writer to move on to bigger things. That’s fine, but it often feels very surface-level. Reading Gimmie, though, I felt the opposite. The one with Coco was absolutely incredible. I also read the one with Julian from Negative Gears, and the way he talked about Canberra, going down to Melbourne, and being in Sydney really struck me. I’ve known Julian for a little while, but I’d never spoken with him about any of that. It was something I only found out through reading the zine — something no other zine I’ve read has given me.

That makes me so happy to hear that. I often get people telling me that they read a chat on Gimmie with a friend and they find out things they never knew about them. Having people open up to you is a really special thing and it’s something that I really cherish. I’m very lucky that people trust me with their stories. Gimmie will always be about stories, sharing interesting and cool ideas and experiences, and music and art with people. I never want to be a promotional platform. That’s not us. Other publications can do that.

JW: Reading yours is refreshing. I get to read, watch and hear so many different things. When you asked me to chat, I was absolutely stoked.

I have a wishlist of people that I want to interview, and you’ve been on the wish list for a while. Since we saw you play at Nag Nag Nag. I wanted to chat to about the new record because it’s such a great one and I wanted more people to know about it. It’s one of my fav hardcore punk albums to come out this year. You guys get a lot of love and respect from the underground. I saw Dx [from Straightjacket Nation/Distort zine] say that “Rapid Dye are the best hardcore band on the planet”! And Coco from Romansy said this record is a “future classic”. How’s it feel to get props like that?

JW: Sometimes I feel a bit like an impostor. Then I wonder if it’s warranted. I talk about this a lot with Ryan, our drummer. He’s always reminding me, because sometimes I do feel off. Back in 2022, I wasn’t feeling too keen on the band.

I thought, well, we had a good run up to 2019, then Covid happened. I felt like maybe I wasn’t the same person anymore. A lot had changed — the world had changed — and I wondered if my music still fit in a post-Covid era. Ryan kept telling me, ‘Your stuff’s incredible, it still blows me away. We’re making it classy. I’ve already done the drums, you’ll do the vocals. The songs are written.’ So I thought, all right, yeah. I just needed that reassurance to really feel like, okay, this is something I still want to do.

Since then, he’s helped me so much. I was feeling pretty depressed — like everyone was during Covid, being stuck inside. I’d always been active, going to shows a lot. But he brought me straight back into it. That was a big turning point.

Yay, for Ryan! That’s awesome he’s been able to help you so much. Your album was recorded in 2021, I think?

JW: Yeah.

I know that over time it kind of changed and evolved; in what way? Did any of how you’ve been telling me you were feeling go into the songs?

JW: A lot of them were written in 2019, when we were playing almost every week or every second week. That’s when we had our tour with Glue, and we had quite a lot of momentum. We were really—let’s push this. Then it slowed down.

Finally, in 2021, we were able to get back together again. I was able to hear what the band had put down, but I felt like I was struggling to come up with the lyrics, because maybe what I was talking about back then didn’t relate too much to how I’m feeling now.

I’d go through my old books, looking at all my old lyric sheets, and think, I was saying this, but I don’t feel that too much anymore, because I’ve had a bit of reflection on the life I had before the Covid lockdowns. But I’d still read them and go, that’s how I was feeling at that time. It’s not that I feel like an impostor, talking about problems I don’t have. I’d put them down and maybe reword them to feel more like a reflection of myself, something to really bounce off. So it was a little bit of rewriting, and after that there wasn’t much change.

The first song released from it was ’What Makes You Feel Safe?’ That’s kind of a loaded question you’re asking.

JW: Yes, it is. I’ve had lyrics for this song for quite a while. Around 2016, I lived in a house where there’s a lot of hectic people. And I didn’t really know who was my friend within that house. There was also police coming over all the time. We always had people in our lounge room, like, I’d be going to work at 5am and there’d be people up all night smoking drugs. And I’d never met them before. And then not having a feeling of safety in my home.

That’s hard.

JW: Yeah. But the thing is, I was also using drugs at the same time. So I wasn’t completely innocent in that, but I just had that feeling.

Before I used to go to sleep, I’d lock my door and rope it just in case someone tried to break through. I’d think, what’s going to make me feel safe? Like in the lyrics: Is it having a gun in my hand? What’s going to make me feel safe? Having my friends around? I thought I had my friends around, but when you’re in those situations — especially when it comes to housemates smoking meth — you don’t know how quickly they can turn on you.

At that point my world felt like it was coming down because I had a really bad pokie-machine addiction. I didn’t have money, so I’d smash it in the pokies thinking, this might get me through. I’d win a thousand dollars and thought, I’m sweet, I’m sorted for two weeks.

But I didn’t really feel super safe in the situation I was in. I used to think I’d feel so much better and more relaxed if my friends stayed next door or if I had a weapon to protect me from being hurt. It came more from being scared than anything else. I was being in my head. The song is how I wanted to express it.

I had a similar conversation with Amy from Amyl and the Sniffers. Their album, was called, Comfort to Me. And we talked about, what gives comfort? I think about that stuff a lot. Growing up, my parents were pretty paranoid about the world and people. So I think it’s made extra sensitive to things or maybe hyper-aware.

JW: I know, I put myself in those type of situations. I did smoke meth for a bit, it wasn’t a full on addiction, but I did it, and smoked a lot of weed. I wanted to be around those type of people because a lot of them were painters, very artistic-types. But also, they can fly off the hand and be a completely different person.

I think that’s also true of hardcore — I’ve always wanted to chase, I guess, the more extreme sides of the human condition. I get really attracted to someone who’s been crushing trains, and I think, oh — this guy’s on the other side of the law, in a world that doesn’t exist within my work or even among friends. I almost felt like I was part of this dark side and I wanted to belong to it and have my own. Even then inside I felt very — a scared person, maybe trying to find comfort in thinking that if I find the most extreme thing, then anything else that happens to me won’t hurt as much.

When you did the interview with Tim from Teenage Hate, you mentioned that Sydney hardcore was naughty hardcore.

JW: [Laughs] Yeah, that’s what I felt. That’s a side that really attracted me. I remember going to Melbourne shows — youth crew shows — and hanging out. A lot of people were straight edge. I’ve never been straight edge in my life, but I always wanted to hang out with people with that mindset, to learn something different. But I’d also end up hanging out at 1 a.m. in a subway, I’d be like, hmmm, this is a bit boring. Then I’d come down to Sydney and it’s 2 a.m., and me and my friend would be in the middle of the train tracks, and my heart would be racing. I felt way better — like, I’m doing something crazy. I’m doing something I want to do.

The first Rapid Dye release is called, Keep Sydney Ugly. Where did that phrase come from? Is it kind of meant like the ‘Keep Austin weird’ or ‘Keep Portland weird’ slogans?

JW: Yeah. Sort of. I was actually thinking about this today. That was when the Sydney lockout laws happened. Tyson Koh, ran in the elections to be voted into the council as ‘Keep Sydney Open.’

We all thought he was a bit of a joke, because it seemed like he was only doing it to further himself, or the people he was interested in. I thought, well, Sydney’s still open — especially within my group of people — because we were still doing whatever we wanted at god knows what hours in the morning. So I thought, let’s have a little play on words: ‘Keep Sydney Ugly’ — keep Sydney half-vandalized, or just… something that makes the city feel alive, even though all the clubbing was closed. I felt like it opened up stuff for us instead of drinking in bars — we’d just be in our houses or on the streets.

I thought, keeping Sydney ugly — that’s how I want it. I want it to stay a little grimy, a bit ugly.

That vibe is so different from where you grew up in the Gold Coast and Logan areas.

JW: Yeah, it’s a lot different. I grew up in Bahrs Scrub, just outside Beenleigh, on acreage. The guys I was friends with were from bushy parts — at least the ones I just felt connected to. I have one friend from that area I speak to sometimes, but otherwise, when I go back, I see people from school and they’ll be like, ‘Oh, you still into that rah-rah music?’ I just never really got along with a lot of people there.

That’s why, when I eventually moved, I felt like I was with people who understood me more. I didn’t have to hide that I was into music or art. Even with my own family, I don’t really fit in — they’re footy fanatics. They just want to watch football or talk about their new car. I’m not really a part of that. When I go home, I don’t feel too comfortable. Since moving in 2012, I’ve been home a few times, but the longest I’ve stayed is about three days. I just don’t feel comfortable in those areas.

Here, I feel at home. I’ve got all my friends, and Sydney feels like my home more than anything.

Was there anything that you’ve kind of found challenging about moving to Sydney?

JW: I pretty much moved with a bunch of records and some clothes, and I was sleeping in my car for about a month. I wasn’t really working. I was still in contact with people I was trying to get away from, because when I was living back in Queensland, I was in this house in Beenleigh where pretty much everyone was using drugs all the time. I was, too, and I saw it as a way to escape.

When I moved to Sydney, a lot of those friends tried to get me to come back with them. They thought, ‘Oh, Josh is just doing a tour to get away for a bit.’ But I was really strict that I didn’t want to be around those types of people. They found out where I was staying about two weeks after I moved, and I didn’t have the willpower — I got trapped in a van with them as they started driving back to Brisbane. They said, ‘Oh, you can come back,’ and I was like, I need to grab something out of my car. So I convinced them to drive me back to my car and basically boosted all the way before they could catch me. I got out, parked my car in Enmore. I was like, I don’t want to deal with these people anymore. I really just went blank. That same day, I thought, this is my time — I’ve got to get away.

I went and applied for a job at Repressed Record in Newtown. Flat-out denied. [Laughs]. That’s fine. But about a week later, Nick from Repressed posted — maybe on Facebook — that they had a room available at their house. I thought straight away, I love Nick’s stuff. I love Royal Headache. I love RIP Society. This is what I want to be part of. I moved in straight away, which felt like a godsend — divine intervention. I thought, I’ve been given an opportunity with someone whose music I love and enjoy, and a chance to insert myself into this scene. I had to take the opportunity. From there, it pretty much worked out.

Did you learn stuff from Nick that you used used when you started your own label, Sexy Romance?

JW: Yeah. I’d talk to him about, how many should I get? Or, should I do this? He’d flat out tell me sometimes, ‘Don’t do that. Keep it a small record. Don’t overspend amounts and don’t go to other companies to promote your stuff. Just do it all yourself.’ Even just watching how he did Royal Headache, and Native Cats. He had a, do-it-yourself, if you build it, they will come thing. So, that’s what I did. But I wanted to make it a little bit sleazy. When Sexy Romance got made, I had no idea what I wanted to call the label. I knew I didn’t want to call it what every other hardcore label is called, like, Angry Hammer Smasher Records or something like that [laughs].

Drew found a book at this pub that we used to go and on the top of the book, it says: Sexy Romance. He’s like, ‘This is perfect. Call it something that’s kind of gross, and you can’t tell it’s a hardcore label, you can’t tell what type of label it is. It almost sounds like a pornographic movie thing.’ I was like, OK, let’s just do it. Let’s see how it goes. And the name really stuck. I’m glad I zagged instead of zigged.

It’s funny that your label is Sexy Romance and the Rapid Dye record is coming out on Valentine’s Day. Someone could think that you’re actually a secret romantic!

JW: I like to think that I am. I’ve never really been told that before, but yeah, I think it probably does sync up pretty well [laughs].

Maybe its subconscious and it just comes out and you don’t even know it?

JW: It’s true! [laughs].

The song after ‘What Makes You Feel Safe’ on the album is ‘Wheel of Fortune’. Is that song about fate? Or cycles?

JW: The fortune is, I was in this cycle — maybe 2016, 2017. I was working this job with Drew from Oily Boys. We used to etch metal blocks for old printing presses. It was one of the last one or two places in Australia still doing that.

Pretty much half the job was me working on the computer. I’d give it to Drew, and then he’d finish at like twelve or one. Straight afterwards, I’d be left on my own. It wasn’t a good-paying job, and I think I used to feel kind of alone. Drew would already have gone home, and I’d be like, Okay… I’ll just go home by myself. But instead, I’d go to the pub.

That’s when I started getting really into playing the pokies. My parents do that a lot, and when I was younger it was always around it — them betting on things, talking about how much they’d won. Around that time my brother had just won fifty grand, and then I found out my parents had won about twenty. I thought, Oh, that’s the way I can get out of this slump I’m in.

At the time I was constantly overdrawing my bank account to pay for weed and drinks. I convinced myself I could fix it all if I just kept playing pokies. But it got to the point where I’d get paid and my whole paycheck would disappear — already gone, lost.

I got used to living right on the edge: not knowing if I’d be eating that week, or drinking bottles of Moët and spreading it around with my friends. Money was such a huge thing — it still is, for everyone. It pretty much runs our lives. And yet I was so happy to throw it away for the chance I might win. Deep down, I knew all I was doing was feeding the hotel owners, giving money to the people I least wanted to give it to.

Looking back, I think about what I could have done with all that money. I could have donated it to charity, or invested in making more records. But at that time, I was very depressed. I kept telling myself, If I just win big once, I’ll be fine. I can get out of this mess!

And sometimes I did win — a couple of grand. I’d pay off my debts, feel like I was fine, then throw it all back in again. It was such a dangerous cycle.

I have Drew to thank for breaking me out of it. And my mum too — she helped, up to a point. But really it was Drew who slapped me out of it, who got me thinking about what I actually wanted to do with my life. He helped me start working towards a life I didn’t want to escape from.

What did you work out that you wanted to do with your life?

JW: I think, because I’ve worked so many jobs, that I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. All I really wanted was that, when I finished work, I could just listen to the hardcore, hang out with friends. It’s only in the last couple of years that I’ve realised what I really wanted to do—I’m on my way to becoming a mechanic.

I work for Sydney Buses now and am slowly getting into skills-based learning. It’s been a happy journey. It’s actually a job that I really enjoy.

That’s awesome. I grew up around a lot of car stuff. My dad had car yards and he was a race car driver. My brother races cars too. So there was always cool cars around. My bro had one of those panel vans with the airbrushed sides; he had the Grim Reaper.

JW: Oh sick, that’s awesome! Danny from Demolition, he’s got one of those.

Cool. You play bass for Demolition, right?

JW: I do, yeah.

Let’s talk about song ‘K.O.P.M.O.H’ on the record.

JW: It stands for ‘Kings of Punk, Masters of Hardcore.’ This is something Drew would say about Rapid Dye. I decided to write a song about it. One, because it sounds kind of cool—I’m like, okay, Kings of Punk, Masters of Hardcore, that’s a cool thing. But sometimes I just thought, oh, it’s just Drew taking the piss.

So, I don’t know if you’ve seen the lyrics. It’s pretty much me talking about it more like an ego boost. But then I have to think Is it an insult? Or is it kind of being an insult? Is he like teasing me, that type of thing? It was more just my own self-doubt going on. Am I happy in saying that I’m this type of person? It’s just funny. I just thought it had a cool ring to it.

It’s already on our Best Hardcore Record of the Year list!

JW: Aww thank you so much!

Who else has put out a better one?

JW: Thanks! I’m always hoping the Oily boys will get back together. I really wanted them to play the release show. I was messaging Drew. Drew was keen but pretty much talking to everyone else, they were like, ‘Give up! It’s not going to happen.’ [laughs].

The next song on the record is ‘Cream’. It’s one of the newer ones you’ve wrote?

JW: Yes, it is. ‘Cream,’ is also a lot about money—but more than that, deep down, I think it’s maybe about my brothers. I have this weird relationship with them. They’ve lived pretty intense lives, like me—they’ve done wrong things, made mistakes—but they’ve managed to get their lives, or what they consider their lives together. They see me still living in Sydney, not settled like they are. They’re just doing stuff, and I’ve got both sides of it.

One of my brothers is a chronic gambler who goes nuts, but still somehow manages to pull it all together. I feel like they see me as a step below them, and even though I know they don’t think that consciously, sometimes it feels that way. My brother is always telling me, ‘Do a trade in this, don’t do a trade in that, do it this way,’ and I manage to figure it out.

It’s me trying to reflect back to my brothers: I’ve done the same stuff as you; I just haven’t locked in as much as you have. The song is maybe more about jealousy—both theirs and mine—or just how I feel in comparison. Maybe I’m more jealous than anything, honestly. It’s like, they’ve done the same mistakes I’ve done, but I feel like they’re in a better situation than I am, or at least the one I’ve put myself in compared to what they did.

But you have put yourself in a better position than you were in previously. You’ve got your trade and you like your job, and you’re putting out your band’s record. All these are great things. I feel like you’re too harsh on yourself, dude.

JW: I do go really harsh on myself, and I don’t want to—but I do compare myself to people that I really care about. I do acknowledge that I really want my brothers to see me as equal, not as someone who’s still kind of trying to work out what he’s doing.

It was a really good time at my brother’s engagement party. He had one of his friends come up to me and say, ‘I’ve seen you play in a hardcore band—I saw you play in Brisbane.’ And my brother was like, ‘Oh, Josh’s band? You’ve seen Josh’s band?’ My brother just didn’t believe it—I’ve had my brothers maybe come to one show the entire time I’ve done music.

It felt like a bit of confirmation, you know? Like, okay, if my brother thought this was kind of cool, I’m glad—it’s somewhat like starting to get rid of that doubt instead of being very strict with myself. Yeah, I think a lot of this is inside my head, but I just tried to put it down into song. I tried to lay it out and make sense to other people.

Writing stuff down in a song and getting it out live; does it help you make sense of stuff too?

JW: Yeah, I do think that, especially when I start doing a lot of the songs, I start thinking about everything that I’ve written. I told my parents about it, and they were just like, ‘Oh, yeah.’ But then I sent them a photo of the record, and they were like, ‘Oh, is that on real vinyl? Is that a real record?’ It was amazing.

They know nothing really about music, but because it was something on physical media—they’ve seen photos of me playing, they’ve been to shows—having something on a record kind of feels like I’ve accomplished something. It’s something I want to do, and it actually made them quite happy.

So, it feels good—having put something solid down, something almost like a marker. I’ve proved to them that this is really something I care about. I remember when I was younger, my mum absolutely hated driving me to hardcore shows. She would just watch the people at the front and be like, ‘I don’t know about them. Are you going to be around rough people? Or are you trying to piss us off by being a bit of a punk?’ And it’s like, no, no—it’s just something that I’m really, really interested in. It’s good.

That’s nice your parents saw your record as kind of a legit thing you’ve done! My mum was always super supportive of me wanting to write about music. When I was in high school, I had international bands calling the house for interviews for my zine and my mum would answer the phone and talk to Mike from Suicidal or Henry Rollins before I got on the line. She once told an old boyfriend that was putting down some bands I love that ‘Music is forever and that it’ll be here long after he’s gone! [Laughter]. She was right!

Or one time, we were in Sydney driving around and saw a pole poster for Frenzal Rhomb taped up. My dad pulled over the car, and my mum jumped out with her Swiss Army knife and cut the poster down for me because she knew I loved them at the time.

She also once got me door-listed for a Napalm Death show because she and my dad were sitting next to them having breakfast in a café. She recognised them—because she knew them from me liking them—and got their autograph for me.

JW: [Laughs] That’s awesome! I remember when I was getting into hardcore, I had to sneak records home because my mum absolutely hated heavy stuff. I remember being grounded for two weeks because I had a picture of Iggy Pop on my MySpace page, and she was like, ‘I don’t want you looking at that drug addict.’ [laughs]

It’s really interesting—even though I had those restrictions, I think it just pushed me to want it more.

I get that. ‘On The Take’ is next up on the album. It brings to mind corruption.

JW: It’s a bit of a slang word for… well, it’s kind of hard to explain. It’s about degenerate gamblers when they gamble—especially when it comes to something like blackjack. If the dealer changes at a certain time and you lose ten in a row, it’s considered, in gambler terms, that the house is ‘on the take.’ It’s like the prime time when they’re going to be taking the money.

So, you either learn to back off or you double down, because usually, when the take comes off, that’s when they get five times or even fifty times your cash back. It’s a learning process. When I started doing that type of song, I was like, oh, this is going into a bit of a degenerate gambler brain, and I’m trying to put that down on paper.

In Australia, in general, per capita, we’re some of the biggest gamblers in the world. I’m really for stopping betting ads or limiting them, just to protect people more. Like my brother—he’s got kids, and I’ve heard stories of his five- and six-year-olds, telling him, ’Oh, you should bet on this,’ just because they watched the ads. They just see the advertising and think the purpose of watching a game is to earn money from it.

So, I think a big thing about this album is the gambling culture, especially within Australia. It’s something I’m not really a part of now, but I feel like a lot of people do have this problem. I wanted to get something out of it. I wanted to break this cycle. I want to start creating more. That’s pretty much why I made it.

I’m surprised at how many younger people I know that gamble, especially on the pokies.

JW: Yeah. There’s like an underground mafia, and a lot of it is money laundering. You see a lot of it where I was living in Earlwood, which was part of Bankstown-Canterbury council, I think that’s the deepest, or maybe the biggest, per capita for gamblers.

A lot of it—you’d see the people going to these pubs. Many of them are hectic: they’ve got big Gucci bags, huge roided-up guys, and they’re just putting thousands of dollars in there. But everyone knows why they’re there—it’s just laundering cash.

It’s almost just seen as a place to be, to be around these hectic types. That’s why I think the imagery goes well, especially in the Sydney central code. It felt like a very Sydney theme when it came to doing the album—that’s something I used to struggle with.

I feel like there might be people I know now who are struggling with it, and can relate to it, just because Sydney is a really expensive city. Everyone’s trying to jump over each other to get ahead and looking for easy money. I feel like that’s just the way some people think.

Yeah, I guess people just feel desperate. Before I was born, my dad was a professional punter, that’s what he did for a job to support our family.

JW: Yeah.And it’s a big thing. My pop dude passed away in 2003. He used to work at Sydney Uni, but he would go punting quite a lot. My mum used to tell me stories about how he bought a brand-new car because he won one thing, and then paid off the rest of his house. They used to get renovations done, too.

Back then, it used to be, half the money you’d earn from your job, and then the rest would come from watching the races in his little chair at the back in his little Punchbowl house. So it’s just been a bit of a culture I grew up around as well.

Yeah, man. I remember watching my mum buy Gold Lotto tickets every week. People don’t really see that as gambling, but it is. She’d be sure that this week would be her week, and finally she could do this or that with her life. But she never really won big, and it’s like she put her life on hold—the mentality of, one day when I have money, I’ll live my dreams, not realising she could still do a lot of the stuff she wanted without lots of money.

JW: Well, that’s it. I think it does feel like you’re just stagnant in one place. The mentality is: as soon as I win, I’m free to do whatever I want. Instead of gradually working toward where I want to be.

Since 2016, I’ve started the band, and now I’m releasing an album. I’ve made everything I wanted to do, instead of just waiting and wasting my money, trying to achieve something I wouldn’t have been able to if I hadn’t focused in the right space.

I’ve got friends from all different walks of life, and some people are really well off, but they’re not happy. They thought that when they finally reached wherever they wanted to get and got money, they’d be really happy. But often they get there, and it’s like they worry and stress more. Having money kind of amplifies all the problems they already had. Same goes for people I know in crazy-famous bands; a lot of them aren’t as happy or together as you think. You couldn’t pay me to be famous.

JW: It’s true. I haven’t had that situation yet [laughs], but I feel like it would be one of those things. I talked to my brother—he’s a FIFO worker, he works in the mines. Sometimes he explains it as the golden handcuffs: ‘Oh, I’m working so much, and yeah, I’ve got all this, but I’ve got no one to hang out with when I’ve got two weeks off, because everyone at home in Queensland is at work.’ He has to fly so far away from family.

Sometimes, when he would come to Sydney, he’d stay at mine. He’d be like, ‘Oh, we’re gonna go to the pub now, we’re gonna go do this.’ There was one time I used to live near a place in Chippendale, and they had this hot chilli challenge. He loves eating chilli—he can eat the hottest things ever. He said, ‘I’m gonna do it because you can get your Polaroid taken and they put it on the wall forever.’

He was excited because places in Queensland don’t have these things. He’s like, ’If you go to this pub all the time, you can just see me up there.’ So he ended up doing the chilli pizza challenge and got his photo on the wall. He said, ‘Oh, this is the stuff I’ve been missing. I can’t do this if I’m just working all the time and trying to pay things off.’ It puts things in perspective for him because he can’t believe some of the life I live.

When I was younger, I could go down to Melbourne for a week and not have to pay for accommodation because I could stay with friends. He’d be like, ‘Oh, you’ve got friends down there you can stay with?’ For him to go down, he’d have to plan time off work and stay in a hotel with people he didn’t know.

It’s interesting we often can think ‘the grass is greener’ for someone else. You both have freedoms but in different ways. He may have more cash but you have friends all over, do something you really love and have solid support networks.

JW: Yeah, that’s true. It’s good to have perspective.

The next track on your record is ‘Bite’ which sounds extra aggressive.

JW: Yeah, it is a bit [laughs]. I write that when I was really angsty.

On the Gold Coast, I always felt like I never got a solid run of doing bands. And there were some people that I saw getting—not exactly acknowledgement, but I felt like, oh, they’re getting to do what I wanted to do. The song was meant to be on the 7-inch that we released in 2017 or 2018.

I used to get kind of jealous. I’m like, oh, I can do that too! And I’ve got some lyrics in that are just like, I took him, and I stole your sound, as if I poached the people you wanted for your band and I took the sound that you wanted to do. Because, I can do it better.

That’s very braggadocios of you! Kind of like a hip-hop track in a way.

JW: That’s exactly it!

Does the next song on the album ‘Again’ also tie into the gambling theme?

JW: Yeah, pretty much. The cycle of it—the “I’m back up again” life cycle. That was my whole life through 2016.

I heard you talk on Tim’s radio show, Teenage Hate, about the song ‘Penance’. He thought it might be about some kind of religious theme. But you were like, ‘No, it’s actually about the video game, Final Fantasy.

JW: Yeah. Around 2018 or 2019, I was playing a lot of video games. I used to still play JRPGs—Final Fantasy in particular. In Final Fantasy X, there’s the big boss, named Penance. He comes with two arms and a huge chest, and you have to defeat the arms first before you can defeat the chest.

It’s kind of like… you can’t win right away. There’s a stipulation that you can’t win until your health is at 1 HP. Then you’re able to attack them. I thought it was fascinating—the way you’ve got to beat them is that you’ve got to get hit the perfect amount. If you don’t get hit enough, or if they hit you too hard, you just die. But if you hit that perfect amount, you’ve paid for your sins—you’ve just got a little bit of life left. Then you can go kill your God or whatever.

It was really funny, a hokey song, and I was like, ‘Oh, this makes it sound way more biblical than I really wanted it to be.’ A lot of people do ask me, ‘Is this something from a verse from the Bible?’ But it was more just a fun song to throw in there, in the breakdown, I love hearing people chant: ‘You’ve got to pay Penance.’ But all I’m doing is just yelling about the boss of Final Fantasy X.

That’s funny! It’s cool you through a fun one into the mix when all the rest are heavier themes. Lightness can hardcore punk is rad.

JW: That’s what I thought too. It was fun to write. The song goes really well live. We’ve had it since the Tour Tape. I was doing songs that were a little bit sillier.

On our 7-inch, there’s a few more silly songs. I’ve got really dumb ones, like ‘I Want to Be a Cowboy’ [laughs].

Thinking of it now, I guess that was during my rock-n-roll stage. The scene was really big in Melbourne, and everyone was really into AC/DC. I was like, I really want to have a rock-n-roll song, to be part of that whole crew.

What was the first Rapid Dye song you wrote?

JW: ‘Dark River’.

That’s what I thought! It was on the first demo and then the 7-inch, and it seems to always be in your live set. I figured it must have been a special one.

JW: Yeah, a lot of people really like that one. Sometimes I feel like it’s so slow, but when we play it, we go, and it really get into it. There’s a funny clip on YouTube of Garry just missing the counting, and you can see Owen, shaking his head at Garry. And I’m just repeating the first two verses over and over until Garry’s like, ‘Oh shit, I’m meant to be playing here.’ [laughs].

That song is more of what we were talking about before: chasing the darker sides of hardcore and life in general. That spoke to me a lot more, like—I’m stuck, but I don’t want to get out of this dark, murky river. I’m pretending that I don’t like the descent when I really do. I like that work, going into chaos.

Do you find it hard to write lyrics?

JW: I do sometimes. Usually, how I write them is how I want them to sound on the record; really impactful. What’s important when it comes to hardcore, in general, is having a really punchy vocal sound. Then the lyrics can fit within that—within the sounds that I’m making.

I’ll listen through a song, play it again, and then I’ll record on my phone—just me grunting or yelling gibberish—to try and fit how I want it to sound. Then I’ll make up the words that fit. That’s how I’ve gotten the songs to where I’m really happy with them, instead of trying to squeeze words into the song. You probably read the lyrics and some of it doesn’t sound too coherent.

I was even talking to Coco, and he was looking through the songs and said, ‘I’m going to change a little bit here,’ so it sounds a more coherent.

Didn’t it take you a while to get the vocals to a place you were stoked on for the new record?

JW: Yeah. I had a whole book with lyrics. Recently, with my partner we moved and packed everything up, and I haven’t been able to find that book, which had everything written down.

I was on the phone with Coco, listening to the song, writing things down, trying to remember parts. I’d look through my phone and be like, ‘Okay, I wrote this for this, but that was the previous draft.’

I started from scratch again, but it was a good thing, because I found out that I could work off what I was actually saying in the recorded bits. In other releases, sometimes it doesn’t sound like the lyrics I’ve written down. I’ve obviously written them, but when I record, I leave what I feel fits in that area.

I had Drew saying, ‘That’s not what you’re saying. This is completely different.’ And I’d be like, ‘Yeah, I know—I wrote it before, then did the song, and completely forgot about it.’

One thing he loves to bring up, though, is on the 7-inch, I didn’t do a spell check, and it says a Destory instead of Destroy. Every five minutes, he sends me a text like: Destory. Destory. Is there another Destory in this album? [laughs].

Aww. I’m sorry he ribs you so hard. I work as a book editor for a day job, and no matter how hard you try and how much you look at something, sometimes you can miss stuff.

JW: Yeah, that’s so true. But “destory” is also kind of cool [laughs]. It’s like, what is the story?

Maybe you can write it off as artistic license! Rappers alter words or how they phrase things to fit stuff better.

JW: [Laughs]. Yeah. Its art!

I love how at the beginning of the song ‘Cream’ you left in the talking—‘Are you recording?’—at the start.

JW: That was accidentally left in [laughs]. There’s another bit in one of the songs, maybe ’On The Take’ where you hear Ryan go, ‘Fuck Felipe!’ and then he starts playing it again. I’m like, ‘That’s cool. Let’s just leave that in.’ The only problem with that now is, because I’ve listened to that version so many times, when we’re playing at jams, I wait for the cue to hear Ryan go, ‘Fuck Felipe’ and play a part again. And I get really tripped up on it and I don’t know when to jump in. It’s funny!

It is! You guys recently printed up some “Pick your Queen” shirts in homage to Poison Idea’s Pick Your King album.

JW: Yes. I love that Poison idea album!

Me too!

JW: I was thinking; what would be the Australian version of that? And I thought of Sophie Monk [laughs] but I just didn’t know what to put on the shirt. But I wanted to explore more classics to pay more homage to Poison idea. And I’m like, okay, let’s go with Dolly Parton, because she is like absolutely loved by everybody. And then there’s Mother Teresa, which is a saint, but also because of the dichotomy of some people don’t like her, some people do. I thought, that’s such a good plan. And I ran it by everyone and they said, ‘Cool. Just run it!’

That’s rad. I did an interview with Jerry A from Poison Idea once, and the internet connection started dropping out—the video call kept freezing. I yelled for my husband, Jhonny, to come help me fix things because he’s really good with technical stuff. I was panicking.

It gets so frustrating when you’re trying to have a chat and it does that, and you lose the flow of the conversation. When we got it working again, he told me that he hoped everything was alright because he’d seen and heard all my freaking out! It wasn’t frozen on his end like it was on mine. I felt so embarrassed [laughter]. He’s the coolest, though, and was so nice to me.

JW: [Laughs]. I felt that before too. It was when I was just 17. I was so excited to see Madball—it was the day before my birthday, and it was an 18+ club, and the club wouldn’t let me in. I remember just standing there, really upset; all my friends had already gone in.

Then I saw Freddie Madball hanging out the front, and I was in such awe and was like, ‘Oh, I LOVE Madball!’ He was like, ‘Come see the show.’ I said, ‘I can’t—my birthday’s tomorrow.’ And he was like, ‘Fuck that shit, come here,’ and just dragged me in through security. He didn’t give a shit about security and pretty much threw me in the middle of the crowd, saying, ‘Stay here so you don’t get hurt.’ It was the coolest shit ever. I must have looked like such a weirdo panicking about trying to get into a show [laughs].

I snuck into so many shows underage. I’d see the all ages one in the afternoon and then sneak into the 18+ at night. Being so obsessed with music getting to see my fav bands twice in one day was so amazing!

JW: I saw Against play and that was one of the more pivotal hardcore bands I’ve seen and gone, ‘Oh my God, there is so many 18+ year olds with no shirts on beating the shit out of each other. What the hell have I just like got myself into?!’

I used to see Against play all the time. I met Greg Against before he started playing in bands, like back in the 90s. I went to high school with his brother and Greg was a couple of years above us. He’d also come into me and my brother’s skateboard shop after we left school. People used to tell me about how hard and tough he was but I always saw him as the NOFX and Bad Religion loving dude from the skatepark.

JW: [Laughs]. That’s so funny. I have the Against eagle tattooed on my back. I got it with Kevin Rudd’s money so I was about 17. And I remember I thought it was the hardest, like in school I was like, ‘I’ve got a tattoo and you guys don’t.’ I got one because I was so down for hardcore. I thought I was cool [laughs].

All that North Coast Hardcore stuff had a big impact on people, it’s still felt now. So many people went out and started bands because of that scene.

JW: Big time. Danny from Demolition is good friends with Greg now and he sent a photo and he’s like, ‘I need to go hang out with Josh because I just want to go see his tattoo.’ It made me smile, it made me kind of starstruck [laughs].

On the subject of tattoos, I saw that you have a tawny frogmouth tattoo.

JW: Yes, I do.

What’s its significance?

JW: It’s one of my mum’s favourite birds, and she hates tattoos. It was like a weird love letter to my mum but also getting something she hates. Danny did a really good job on it. It’s one of my most favourite tattoos.

That’s so lovely!

JW: It is.

The one song we didn’t talk about that’s on the album is ‘After Formal Party’; is it based on a real event?

JW: Yes. So, 2007 was our after formal party. And it was just like a normal year 12 party, 17-year-olds were drinking and whatever. Then a situation happened where we got gate crashed by 20 to 25 people. Pretty much everyone got beat up and injured. Because it was in the middle of the bush, it took quite a while to get police out there. When police arrived, it was only two of them and one police car and they got set upon. One of the officers got his skull smashed in. And the other one, I had to hide behind a shed with his pistol drawn. He didn’t know what to do because he had a bunch of 16 to 18-year-olds trying to kill the police officer. It was a really, really hectic time. It made the news. I think the sergeant ended up having brain damage from the bottling. It was something that was quite traumatic.

Me being 16 at the time, it was really silly when I think about it. I got suspended from school for it… We got interviewed by Channel 7 out the front of the place and were asked what happened. I was still drunk, and I said to my friend, who was driving out in his pink Excel, ‘I’m going to try and drop as many Iron Maiden songs in this interview as I can.’

It was like, ‘I didn’t know what was happening—I had Fear of the Dark.’ My friend would have his fingers up in the background, counting the song titles I dropped.

[Laughter]

We thought it was the funniest thing ever—until Mum saw it. Then it was over, because as soon as I went back to school, I had to go to the principal’s office. I’d brought the school into ill repute or whatever, and I got a three-day suspension for it.

It was a funny situation and also not funny. At the party, stuff got stolen—it was hectic. They ended up finding the guy who hit the police officer with a bottle; he was sent to jail.

Wow!

JW: It ended up being a big thing… having to see all your classmates that you’re meant to be celebrating with, a lot of them sustaining quite heavy injuries—bleeding out, everyone completely beat up. It was quite a situation.

Is that the most hectic situations you’ve been in?

JW: One of the most hectic is when I was 17, I had a car accident where I’ve accidentally hit a kid with my car. He was playing chicken with the cars at the lights… he missed one. He went straight into my car and actually went through the windshield. His body got flipped up onto the roof, and his skin was stuck to the glass. When I braked, he got flung off the car. I was doused in blood. I didn’t know if it was mine, there were cuts all over me. I saw the poor kid and he wasn’t moving. I didn’t know what to do because I was in so much shock.

Then the ambulance came and looked after him. He broke both his femurs and had his skin ripped off his face. It was like showing his skull! What made it even worse was when my mum arrived at the scene, she just screamed and said, ‘You’ve just killed someone. What the hell have you done?’ Everyone that saw the incident was like, ‘No, no, no. He’s an okay, he’s all right. But that caused the police to escort me to the hospital and I figured I’d take all the tests and to go to the station. I thought they’d think I did it on purpose. The way my mum screamed made them think my character was suss. But I was like, ‘No, this was an accident and its horrible.’

That is so full on! I’m so sorry that happened to you.

JW: Yeah, it was weird because I remember going back to the hospital and still being covered in blood and I was wearing a Lionheartxxx straight edge shirt. The coppers came up to me and were like, ‘I don’t even know why we have to test you? You’re wearing a straight edge shirt.’ He knew what it was.

I was so very happy that the kid was alive. I’ve attempted to get in contact, but I have not been able to find any leads to be able to contact him to see how he’s going.

A lot of creatives I talk to, tell me they learn a lot about themselves trough the art they make. Is there something you’ve learnt about yourself making stuff?

JW: Believing in myself—that I do have the tools and that I feel skilled enough to excel at what I really want to do—doing a good hardcore band that I felt could stand up to a lot of the great hardcore bands I really enjoyed. I’m still learning in the process and trying to do better, to be where I want to be.

Doing hardcore, especially being in a band, gave me one of the most important things: finding my identity, which I feel a lot of people struggle with. I feel very lucky to have been given the opportunity and to have been able to work out who I actually am and who I want to be. It’s one of the best things I’ve learned from being creative and making music.

That’s so cool! I’m stoked for you. What’s one of the most important things to you?

JW: Having a solid family unit—I’ve got my partner, and just having a safe home that I can be around—has put me in a position where I feel the safest and most like myself. I feel like I’ve achieved what I wanted to achieve in my life. There could be other things I do as I get older, but where I’m at now, I’m quite happy. It’s where my life has gone, and I’m really ready to see the future as well, and what I can do.

Hearing that makes me so happy dude. Let me tell ya, your record is one of the best hardcore albums I’ve heard from Australia in a long, long time. It could be one of the best ever. I’ve been away from the immediate community for a little because I got so over it, and for me your album has made me believe in hardcore again. I want a hardcore bands that are fun and less serious.

JW: That’s what I felt was missing from hardcore at the time. Like you said, it got really serious—almost like a job. Very uniform. You had to dress a certain way to be considered a certain type of band.

I smile a lot on stage because it’s one of my most favourite things to do ever: play a show. I get a lot of people telling me, like, ‘For someone that seems like they have such a crazy, hectic band, you’re just smiling the whole time.’ And I’m like… because for me, it’s one of the most enjoyable things I can do. My smiling, gets people to relax a lot more as well—they feel like they can be themselves because I’m trying to embody that on stage myself.

I definitely felt that when I’ve seen you play. And I definitely appreciated that.

JW: Oh, thank you so much, it’s really nice to hear.

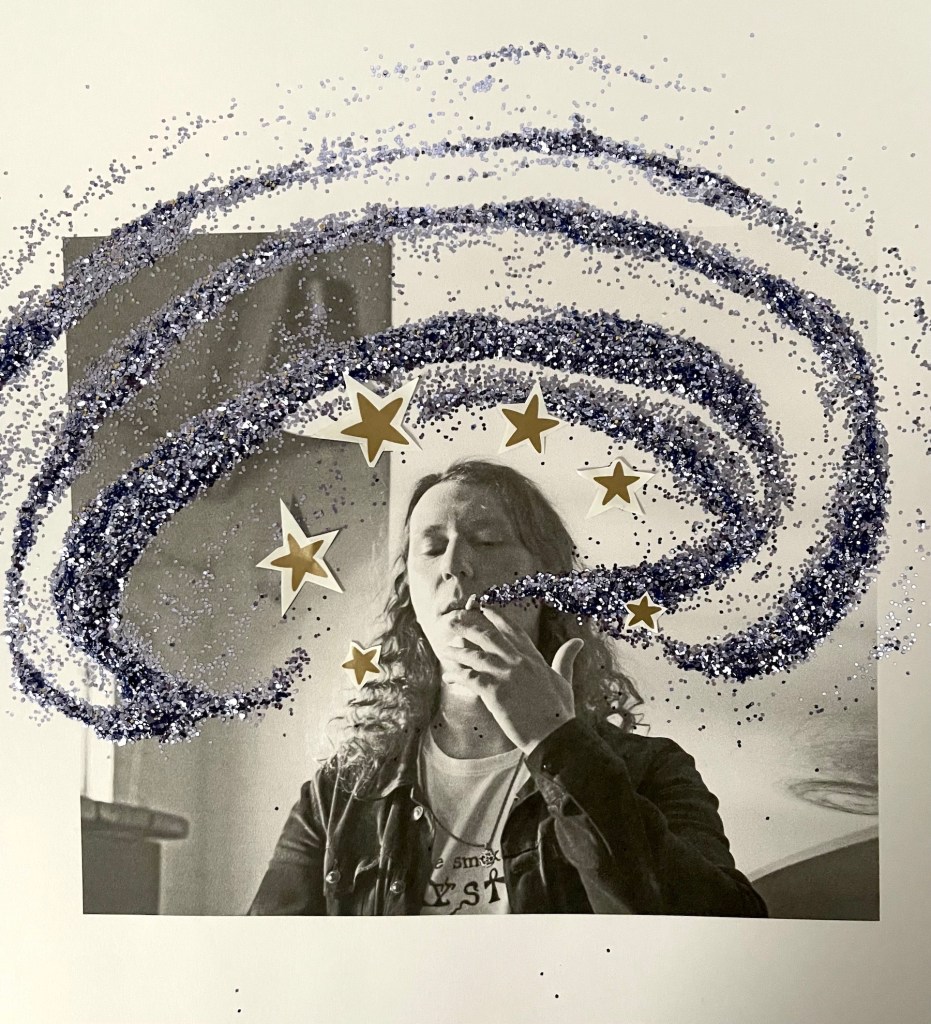

Also, let’s talk about the album cover. That disco ball!

JW: I love the disco ball too. As soon as we saw that photo, we were like, that has to be the cover. Especially Garry—but Ryan, Felipe, and Owen too. When we used to hang out together, all we’d listen to was disco. We wouldn’t even drink alcohol; we’d just listen to disco [laughs].

We love it. Garry’s already got a disco set planned out for the listening party we’ve got on Friday. Disco is such a happy vibe. It gets everyone in the mood to dance. It’s not too serious; it just really taps into our playful natures as friends.

We used to go down to Melbourne and they’d be playing, like, The Victims or something, and then you’d see Garry take over the aux and start playing straight-up disco. And people would be like, ‘What the hell is that? And we’re like, ‘We’re here to party! We want to have fun. This is our fun time—we can listen to punk at the show.’

Amazing! We love disco too. We’ve got a playlist of songs people might think are cheesy, but we love them. If we’re coming home late from a show, we’ll throw it on and sing along to stay awake while driving.

JW: [Laughs] that’s cool! I didn’t grow up in that era, but I remember thinking all the time, like, man, I would’ve had so much fun if that was around. Like, I probably wouldn’t have been into punk, but I reckon I fully would’ve been just as happy doing disco.

I hope you make a disco record one day! Totally here for it. Is there anything, right now, that’s super inspiring you? Or anything that you’re super getting into or just really enjoying?

JW: I go through different addictions — I get into different things all the time. I’ve always been addicted to playing card games. That includes poker, but lately I’ve been playing Magic: The Gathering. I’ve also been playing One Piece and doing tournaments. I get really, really involved in that kind of stuff.

I’m at the point now where — I don’t know if you want to see it — but this is my desk [moves camera around the room]: I’ve got trading cards everywhere, making decks, building things. It’s kind of like my version of problem-solving and getting to talk with friends. I’ve met so many new people through it as well.

It’s a bit bad, because when we were doing the Rapid Dye LP, the band were like, ‘Oh, do you want to jam on a track?’ and I’m like, ‘No, I can’t, I’ve got a tournament, I’ve gotta go, dude.’ There’s a part of me that’s like, Josh, you need to focus on music instead.[Laughs].

I’m still finding the right balance between the two. But honestly, playing card games makes me happy — it’s more about being with people, interacting, and doing something social.

Nice! Anything else to share with us?

JW: Well — when we first started, I wasn’t even friends with Felipe or Owen. Horrible way to first meet Felipe, by the way. Ryan was telling me, ‘I’ve got my friend Felipe who wants to join Rapid Dye.’ I was like, ‘Okay, cool, let’s just hang out, see how it goes.’ So he came over, and I said, ‘Oh, do you want to have a pinger?’ So we had a pinger each, and we’re just listening to hardcore.

Then our friend Jack came over. He was standing at the door and goes, ‘Oh, my dealer gave me this — he gave me all this DMT.’ Now, I had never met Felipe in my entire life. I didn’t know if he was straight edge. I didn’t know what kind of person he was. I don’t know if he was trying to keep up with me, or maybe I was trying to keep up with him — I had no idea. We were just like, sure, why not?

Looking back, I’m like, did he think I was testing him? Like, ‘Let’s see if this guy’s legit or not?’ I didn’t even think about it at the time. Two hours later, we’re both lying on our backs, on the bed, after smoking DMT and having some weird out-of-body experience, going, ‘This is so weird.’ [laughs]. And that’s how we met. We became really good mates, and it’s just been absolutely incredible.

The funniest story, though, with Felipe was when we were playing the Glue Tour in Melbourne. He was like, ‘Oh, I’ve got to go to a talk with Lauren.’ It was due, I think, a few days before the tour finished. He said, ‘I don’t really know what to do,’ and I was just being soft and said, ‘Well, you should probably listen to your girlfriend.’ He whacked me and goes, ‘No! I want to keep playing the shows — you’re meant to convince me to keep playing!’ I was like, ‘Oh, sorry, that wasn’t really good for your relationship.’

But the one who really started it all was Ryan. Ryan was the guy who actually hit me up to do a band. He said, ‘Josh, I want to do a band with you so, so bad. I just know whatever you’re going to end up doing, I want to be in it.’

He told me, ‘I made this band for you — for you to be able to do what you want and be who you want in it.’ And I think that’s one of the most appreciated things anyone’s ever done for me. It really set me up to want to succeed. He could just see something in me, and he pushed me so hard to be into it. That’s one of the biggest things that’s ever happened to me, and I’m really happy about it.

We’re all here to support each other. One of the best things Drew ever said to me when I used to feel down and go, ‘Oh, no one gets me.’ And he said, ‘The reason we’re all friends is because we all like the same fucking shit music, and we like the same art, and we like the same stuff. That’s why we’re all together — because we’re meant to be. We have this bond. I really hope everyone finds their people — and just gets to be happy.

Check out Rapid Dye’s self-titled LP out via Cool Death Records & 11PM Records HERE. Follow: @sexyromance.sydney