OSBO stands as a distinctive force in Sydney’s 2024 underground music community. Their new EP (out on Blow Blood Records) offers a raw, visceral experience that exemplifies modern hardcore punk. Its production strikes a fine balance—fiercely energetic and gritty, yet clear enough to highlight the potency of the songs. It’s a taut 10-minute wire, poised on the edge of snapping. With its powerful bass lines, frenetic guitar riffs, and intense vocals, OSBO brings their own unique edge. With plenty of fast, adrenaline-pumping tracks that capture the essence of hardcore’s loud and relentless drive, you’ll find a soundtrack for both your frustration with the world and moments of healing release. One of the best Australian hardcore punk EPs of the year!

Gimmie was excited to speak with OSBO’s vocalist, Tim, and bassist, Ravi.

RAVI: Tim said he’s running late. He said start without him.

OK, cool. No problems. It’s so great to finally be speaking with you. I can’t find any other OSBO interviews anywhere.

RAVI: We’re pretty low-key [laughs].

We love you guys so much. The first time we got to see you play live was at Nag Nag Nag, and you guys blew us away! You play the kind of punk we love!

RAVI: Thank you. Greg and Steph, who put on Nag… are the best and it’s always a lot of fun. We’ve played that a few times now.

Greg and Steph are totally the best! Two of the nicest people in the community. So, what’s life been like for you lately?

RAVI: To be honest, it’s just been work. I hate saying this, but it’s true—work occupies a huge amount of time. Music-wise, OSBO previously had a free practice space, and the downside of a free practice space was that we were quite lazy. Sometimes we wouldn’t even get together for a few months, or we wouldn’t see each other at all. Now we’re paying for practice, and because we’re paying, we don’t want to skip it, so we actually get together every week now [laughs]. In the last three months, we’ve been more productive than we were in the past year and a half, which is good!

That’s great to hear. We kind of just figured OSBO was a pretty casual band.

RAVI: [Laughs] Yeah, well, we’re all well and truly in our 30s, and work a lot. Everyone’s quite understanding of each other when we can’t play or can’t practice. It’s all very low pressure.

What do you do for a job?

RAVI: I’m an Assistant Principal at a high school for students with mental health concerns.

Wow, that must be such rewarding, and challenging, work.

RAVI: Yeah. I have been doing it for a while. It’s quite a small school, only 56 students. But it is rewarding, you get to see kids grow and progress over a period of time, it can also be quite intense; there can be a lot of self-harm or suicidal ideation. We’ve unfortunately lost a couple of students, which is always hard. Overall, though, the school is hugely positive. Some of the kids are just going through a rough teenage patch, but then they wind up doing really well.

What made you pick that kind of work?

RAVI: I stumbled into it, actually. I was teaching at a regular high school, and got fed up by it and quit. At the time, I was working at Repressed Records in Sydney.This guy was working at another record store in town, and I got chatting with him and it turns out, he worked at a mental health high school, and he hooked me up with work. I like it being small, we don’t churn through kids. I sometimes hear about kids that have finished school a few years ago, and they’re either finishing degrees or working, and doing well. So it’s nice to hear that.

That’s so awesome! I saw on your Instagram that you have a therapy dog!

RAVI: I do—Scout.

[Ravi talks to Scout, ‘Come here. Come here Scout. Say hello!’]

Oh my goodness! She is sooooo beautiful!

RAVI: Scout comes to school with me. I got her from Guide Dogs Australia. She’s pretty awesome. I live in an apartment, so I never really wanted to have a dog because I would feel bad leaving them at home all day. It’s great being able to take her to work every day. I’m pretty appreciative of that.

Dogs are the best! I mostly work from home and our pup Gia is always by my side keeping my company.

RAVI: Definitely. They’re good company.

Have you always lived in Sydney?

RAVI: I grew up in Western Sydney, and then lived overseas for a few years but not long. I’ve lived in Sydney pretty much my entire life. I feel like this is it—an ‘I’ll be here’ sort of deal. I like it. There’s a lot of things not to like about Sydney, but then there’s enough good things to keep me here as well. My sister’s recently moved back to Sydney with my niece and nephew and I spend a lot of time with them, which is really nice.

When I visit, Sydney it always seems so fast paced to me. It’s definitely got a different vibe from what I’m used to, having lived in Queensland most of my life. It’s pretty laid-back up here, especially on the Gold Coast where we are—no one seems to be in a real hurry.

RAVI: There’s parts of Sydney that are really hostile. The rent being so expensive makes it hostile; everyone has to work. It’s not an easy place to just live, which sucks. You hear stories from people about back in the ‘90s where you could just get the dole, play in a band, and hang out. It’s not like that anymore, everyone has to work quite hard to just survive. We have a good group of friends that are close, I’ve known a lot of them for a long time. Like, Greg and Steph I’ve known them for a dozen years. It’s nice to have a community.

One thing that I really love about going to shows in Sydney is that it’s much more multicultural. As a Brown person, it’s really nice to to not be the only BIPOC person in the room.

RAVI: That was a shift a few years ago. Growing up, going to punk and hardcore gigs, it was pretty white. Being Indian, I noticed that where I grew up in Western Sydney was also quite white. It was definitely noticeable, but over the last dozen years or so, it’s definitely shifted, and it is really cool and nice to see. So, I get that.

My experience growing up in the punk and hardcore scene was similar to you, everything was very white. Being a Brown female at shows too, I really felt like an outsider in a subculture of mostly white male outsiders.

RAVI: Yeah. And that aspect was alienating.

Yes!

RAVI: Having the whole traditional Indian parents, they were never like, ‘Go out and learn an instrument,’ or anything like that. So the whole idea of it all was just foreign to me. There was no access point So even though I was going to punk gigs and stuff from a very young age, it always felt like something other people do. It never really felt accessible in that sense.

How did you get into music?

RAVI: It was through a guy who sat next to me in roll call back in high school. He was into a lot of the skate punk stuff, like Epitaph and Fat Wreck Chords. The one local band that everyone seemed to be into was Toe To Toe because they’d play everywhere. If you talk to people my age, I’m in my late 30s, Toe to Toe was often the first band a lot of us saw, ‘cause they’d play the suburbs. Toe To Toe was a gateway band. From there, I’d go to the city and various youth centres to see shows quite regularly.

Penrith was actually where I grew up, so for a while in the early 2000s, it was a hot spot. There was a lot of gigs out there. American Nightmare came and played. In the summer a lot of touring bands (Epitaph stuff) would play.

Yeah. I remember all of that. I’d go see anything. I was just so keen to see bands, and those were the ones I had access to too. I may not even like everything but it was a chance to get out there and be a part of something exciting.

RAVI: I lapped it all up too, I couldn’t differentiate between good or bad stuff for the first couple of years, it was just all excellent [laughs]. After catching a lot of pop-punk stuff, I then that moved into a lot of hardcore stuff. After the mid-2000s, I got into to a bit more garage rock. I guess, I burnt out on hardcore punk. But then came Eddy Current Suppression Ring and I was like, oh god, this is really fresh! This is really cool! And, that kick things off again.

It seems we had a pretty similar music trajectory. I got burnt out on hardcore too, not the music but more the scene…

RAVI: It was too bro-heavy, yeah?

Exactly!

RAVI: I got that sense. But then, in Sydney, there was a secondary punk scene, where there were punk and hardcore bands that would play with Eddy Current or Circle Pit or whoever, so there was that clash of things. I started working at a record store when I was probably 15, and then started working at Repressed when I was 17. Chris, who owned the shop, was always turning me on to stuff, and not just punk-related stuff. He’d be like, ‘Oh, you should listen to Guided by Voices or Modern Lovers.’

That’s awesome. I used to have the dudes that worked at Rocking Horse Records in Meanjin/Brisbane turning me on to different stuff. It’s funny you mentioned Toe To Toe before, Scott Mac, was the second person I ever interviewed!

RAVI: Cool. I often think of them. I had this conversation with Mikey from Robber, and we were all like, ‘Toe To Toe were like the Australian Black Flag of the 90s,’ in a way—just in the sense that they went everywhere. Like, you’d see flyers of them playing places like Townsville or wherever. Even talking to my friend Nick, who owns Repressed now, he said that he saw them in Cairns when he was a kid. I think that was hugely important, they played in places that other bands didn’t.

Yeah. I know you collect records. What are some albums that have been really big for you?

RAVI: Formatively, The Replacements‘ Let It Be hit a spot so much so that, not that I listen to it frequently now, but I’d still call it one of my favourite albums. It was huge for me; I listened to it constantly. The first wave, as a kid, would have been bands like Good Riddance or Sick Of It All. Even now, I’m constantly buying records—lots of Australian stuff. Particularly right after Eddy Current, it felt like there were so many good Australian bands happening, so I’d be catching all of that stuff.

Totally, Eddy Current is such an important band! What’s one of the last records you bought?

RAVI: I bought The Dicks [Kill From The Heart] reissue on Superior Viaduct. I was happy to get it. I also grabbed a couple of things from Sealed Records. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Sealed Records? But Paco who does La Vida Records, he runs a label called Sealed and they do a lot of archival stuff. I got a release by this band Twelve Cubic Feet, never heard of them but I trust the stuff that he’s putting out. It’s good!

What inspired you to start making music yourself?

RAVI: Social stuff, I very much like spending time with my friends. It’s an extension of that. Pretty similar to playing in a team sport or any sort of group activity. Spending time with the same people regularly. I never felt like it was something I could do. But some friends of mine actually said, ‘No, let’s let’s do this,’ and following through, them pushing me to do it.

Was OSBO your first band? I know you play in The Baby as well.

RAVI: Yeah. The Baby. And then, OSBO has a similar sort of cast of characters. So yeah, Lucy from OSBO played in The Baby as well. She’d never played in a band either and just started playing in Photogenic. Max the drummer had never played drums before. Ben the keyboard player had never played keyboards. So, The Baby was everyone just giving it a go.

I love that! I find bands like that seem to create really interesting music to me. I feel like there’s more experimentation, and the naivety, give you a better chance at developing something more unique. We love The Baby when we saw you play Nag.

RAVI: Thank you. It’s very unorthodox. I remember our first practice, Max had to look at YouTube, how to set up a drum kit, he had no idea. Our band is just built around friendship.

Did you ever think you’d be a singer?

RAVI: No, no, no. Other people suggested it. I’m glad they did. It was a similar thing with Tim from OSBO. He’s been a good friend, and he’d come around, and we’d play chess and hang out. Then he mentioned he was starting OSBO, and was like, ‘You want to play?’ I was like, ‘Yep.’ And OSBO started. It took a while to get off the ground because everyone has other things going on.

Had you played bass before then?

RAVI: No, I hadn’t. Joe, our guitarist just taught me from scratch. There were times when I thought, I’m never going to get it! I should quit. But they were like, ‘No, no, you got to do it. We want you in this band.’ They really pushed me, which was awesome!

It’s so good to have that encouragement, support and camaraderie, hearing about that makes me love you guys even more.

RAVI: Yeah, exactly, and I’m really glad they did that. As I said, it’s primarily built around the social aspect, so everything else is secondary. We found our friends in Sydney were always so supportive, but not even just in Sydney, all our friends everywhere are really supportive. From the get-go, people were coming to shows.

Where’d the band name come from?

RAVI: That was Tim. He had that band name for a while, and he had planned on starting a band called that, and various members had come and gone and it just never sort of happened. So it’s very much, in that sense, Tim’s band, I guess you could say.

What’s something you could tell me about each member of the band?

RAVI: Jacob, our drummer, he’s going to be having a new baby very soon. So that’s, parenthood and hardcore coming together—he’s very excited.

Joe, our guitarist, was working an insane job where he was working 18 hours, and he’d even sleep over at work. But he quit and now is feeling a bit more of that life balance. He’s doing really good.

Lucy, our guitarist, she’s awesome. She’s a primary school Librarian and very good with young kids.

Tim, our vocalist, is probably the focus point of the band. He has a good presence. He’s like an MMA guy, so he’s quite fit and energetic on stage. He’s been doing that for a few years. I think it was something that was really good for him.

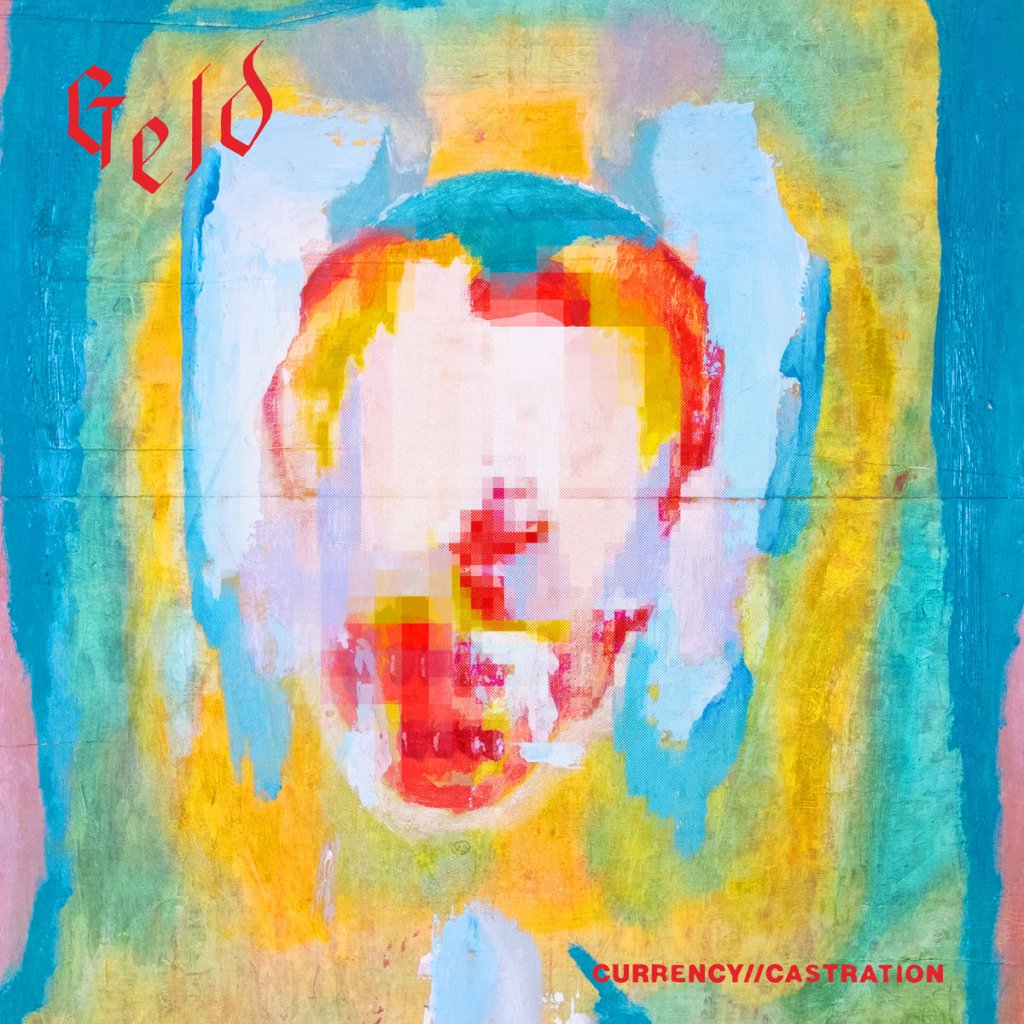

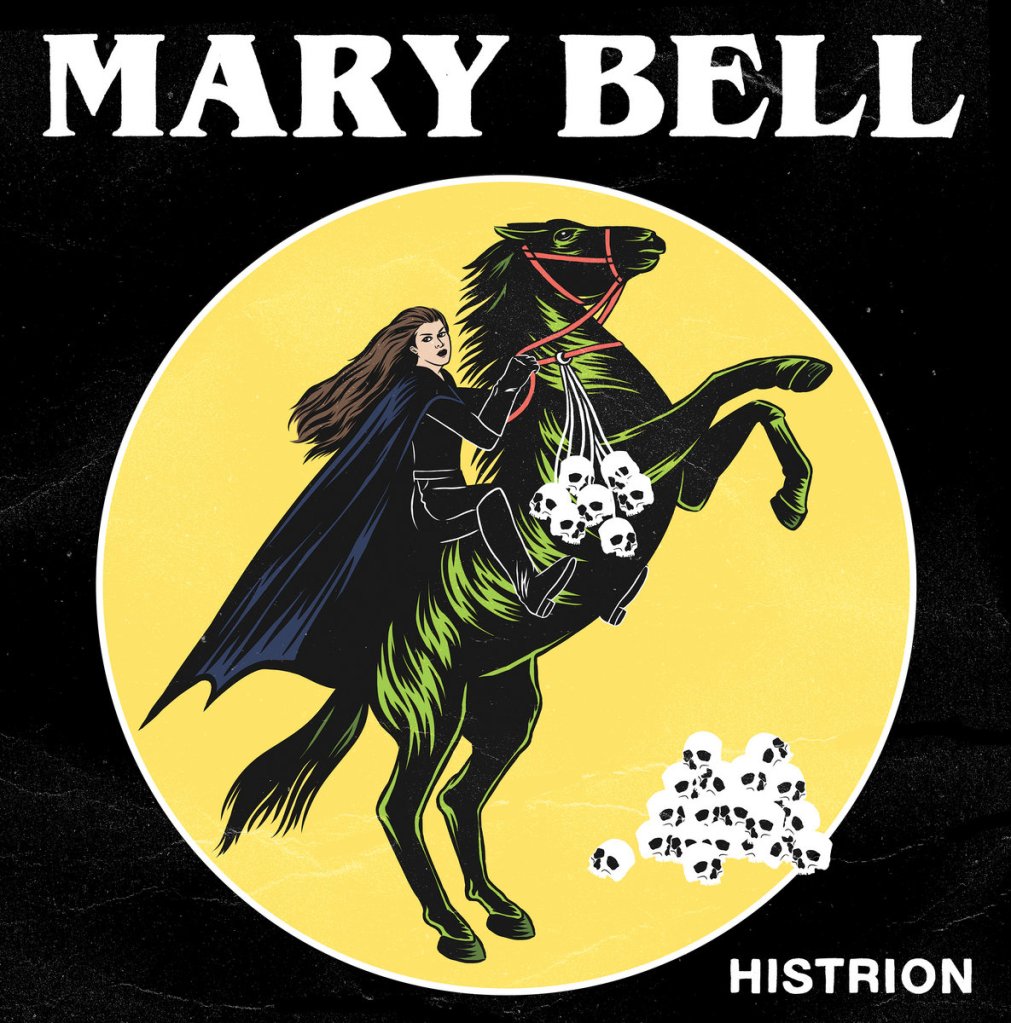

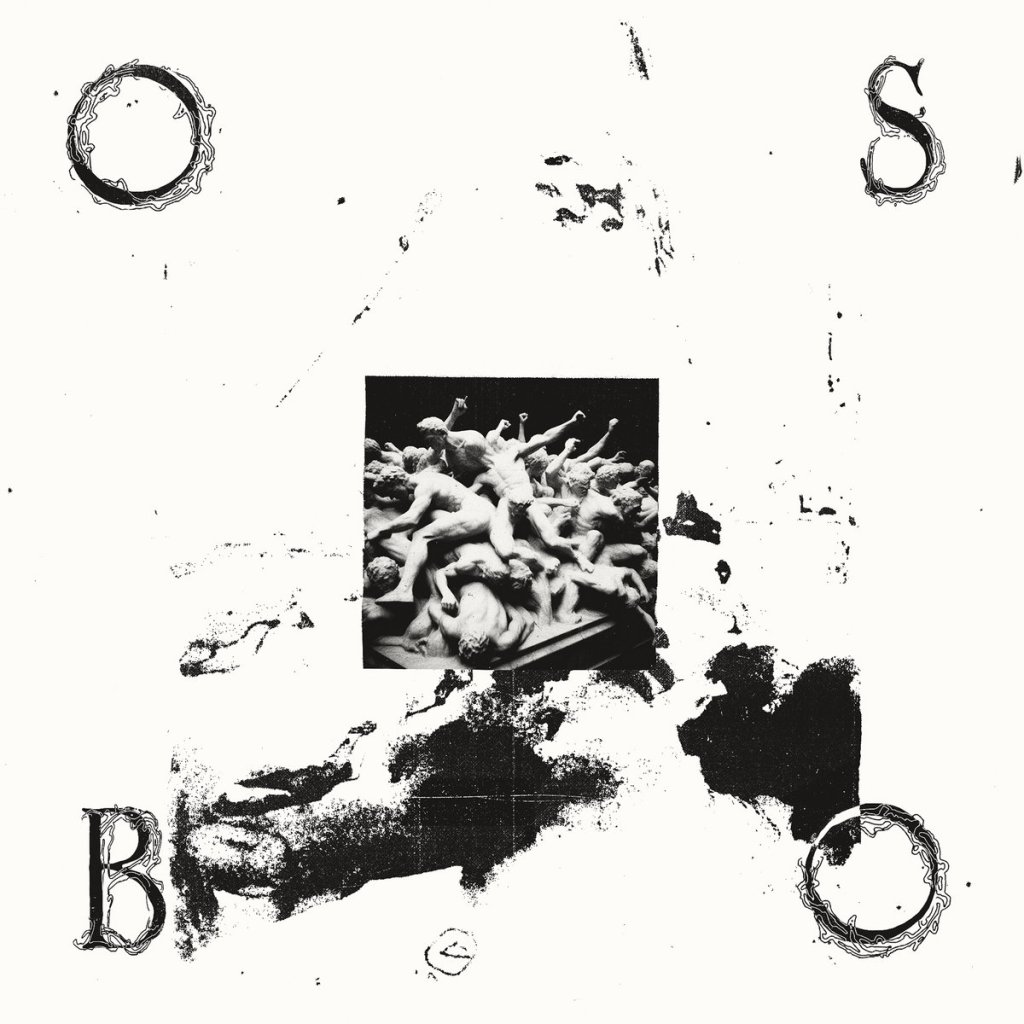

OSBO put out their EP on April 1. It’s really amazing! The art work is similar to the photo on the demo, the pile of bodies.

RAVI: Joe, our guitarist, does all of our artwork. He’s a graphic designer by trade. You’ll spot his artwork on Sydney bands’ records. It’s nice having someone you trust to do the art. I’ve never asked him where the image comes from, but to me, it almost looks like there’s a horse’s head in there, and it reminds me of The Godfather—the horse’s head in the bed. It’s sort of abstract. Maybe I’m just imagining that [laughs].

I’m gonna have to take another look at it now! How long did the EP take to record?

RAVI: We did it over two days, at a random house. The contact came from our drummer at the time, Coil. It was this house in the suburbs that was clearly a rich person’s house in the ‘70s, but was now overgrown. The pool had been filled in and there were trees growing out of everywhere. We recorded in this old pool house. It was run down as all hell.

[Tim joins the chat]

TIM: Sorry, I’m late. I was riding my bike in the Blue Mountains with a bunch of friends.

That would have been really lovely. It’s really pretty up there. I think I saw you post online earlier that you did something 40+ kilometres!

TIM: Yeah, I didn’t even record all of it, so it was more than that.

That’s a lot! Wow. Is that something you do often?

TIM: I’d like to do it more often. Occasionally we go out and do long rides or overnight rides.

You also do Jiu-jitsu?

TIM: Yeah, that’s one of my other things that I do.

RAVI: I mentioned that earlier too.

TIM: It’s fun—it gets you out of your head.

It’s so important to have stuff like that. Do you have any fond memories from recording the EP?

RAVI: The guy who recorded it Ben [Cunningham] had nice gear, a nice drum kit, so that was nice. Next time we might record with friends in Melbourne.

TIM: I was stoked that we got to do it in Macquarie Fields, and it being so close to where I grew up. Also, having that connection into somebody like Ben who’s younger, and who is doing something new, rather than it all just being like, if we’d gone and recorded with David Ackerman, it would have felt a bit different, you know, like recording in Marrickville or whatever.

The whole experience to me was so different to the other recording experiences I’ve had. It felt more like of the band as well, and it was cool to like have Coil there as his last thing to do with us as well.

Other times I’ve recorded were either even more DIY or like more professional. And this was sort of somewhere in this weird kind of space in the middle, whilst being in the back of somebody’s house in the suburbs, 40 minutes from the city. It’s kind of this strange space that felt very DIY, but also very earnestly trying to do a great job of that.

RAVI: Ben did a great job. If anyone is keen to record—hit Ben up!

It’s a pretty intense collection of songs; was there anything you did to get that vibe?

TIM: [Laughs]. It’s kind of weird. It was a very chill day. We were sitting around. There was little bit of back and forth with the tracking. I did every song but one, in one take.

RAVI: We were a bit concerned that Tim was going to blow out his voice, because he gives it 100%.

TIM: [Laughs].

RAVI: We were hoping that didn’t happen.

TIM: Because I wanted to do it in one take, I went particularly hard at each song. We did just spend a lot of time just like chillin’ though.

RAVI: It was pretty low-key. There was a lot of sitting around in the overgrown backyard, with a tree growing through a bench, and a bicycle stuck up in another tree. There was this other shed that we went into and it was full of old movie posters…

TIM: And, dentist stuff.

RAVI: Yeah, and stuff from junior football teams from the 1970s. It was a weird vibe.

We’re glad you were able to capture the ferocity of your live show on record. Often I find, a lot of bands miss that mark.

TIM: The imperative of the band is that we’re all pretty much on the exact same page about what we’re trying to do with the band and what our references are. Because of that, we go into that kind of situation knowing that’s what we want to capture about the band.

RAVI: We were conscious that we didn’t want it to sound too glossy.

TIM: I think it would be hard for me to sing these songs and not like blast on them. It needs to be full on, otherwise it’s not the thing that we’re trying to do.

A lot of the songs on the EP are from the demo…

TIM: Having practiced them a lot more, makes a big difference [laughs].

RAVI: The demo was done with a Zoom mic at practice sort of deal. We recorded it and sent it out.

TIM: Yeah, we probably should have done a better job with that.

RAVI: [Laughs]. But I feel like it captured what a demo was meant to be.

TIM: We re-recorded because the demo was so scratchy. We’re now in a spot where we’re practicing a lot more, writing a lot more. We’re working more consistently. COVID lockdowns, that kind of happened right in the middle of when we were starting to do stuff. Now we’re aware that we need to be tighter to be that sound as well. We need to be able to know the songs inside out before we can go into a recording situation and produce that kind of intensity.

RAVI: Hopefully we’ll be able to record again before the end of the year or if not early next year.

Yes! That’s great news. Do you have many new songs?

RAVI: A couple of new songs but then a bunch of part songs.

TIM: Since the EP, we probably got like another three or four.

With the songs that were on the original demo that you’ve re-recorded, were they written back around like 2020? Was there anything that was happening in your lives that was influencing those songs?

TIM: It wasn’t a particularly nice time [laughs]. I remember talking to Joe even before we started the band; I just felt like, politically, people were just very angry. There was a lot of stuff that had completely failed, and there hadn’t been anything to inspire hope or a positive outlook. When stuff like that happens, really good hardcore music gets made—which makes it sound a little cynical.

RAVI: It was a weird time, definitely.

TIM: Not for me personally, but I think it was an angry environment, and I just wanted something to put that in, and so I put it into this.

What about the newest song, ‘Say It To My Face’?

TIM: Same deal. A lot of the songs are about work, which is a very stressful and unpleasant environment. I have a professional job. I work in an office. There’s a lot of politics and that kind of thing. So a lot of the songs are just about me wishing I didn’t have to deal with those people.

I feel that, in my work experience, I know I’m not really built for an office.

RAVI: The song ‘Time’ probably captures that. Like, people who abuse your time in the work setting, they’re almost like vultures.

TIM: Yeah. A lot of the songs are about feeling like you have to deal with things against your will. Like, I don’t want to go into those scenarios. I don’t choose those scenarios; I would prefer to not have to ever do any of that stuff. And then people make it worse, like ‘Say It To My Face’ is basically about people talking about you or your work, but not having the guts to tell you, and how frustrating that is to deal with—which is a general situation at work. But there were also some specifics I was dealing with at the time that I was extremely, really, really not enjoying.

I’m so sorry to hear that. That sucks.

TIM: I wrote a nice song about it.

What are the things that you do to counterbalance this shitty things, like, stuff that makes you happy?

TIM: Write nasty songs about it.

[All laugh]

TIM: Like we were talking about, I have Jiu-jitsu and cycling, and they’re really good outlets for dealing with mental health issues or dealing with just not being able to get out of your head.

RAVI: I spend time with my niece and nephew—that forces me to be present and put everything else to the side because. Like, you can’t be zoned out thinking about work or anything like that.

What else do you do outside of music?

RAVI: I go to see a lot of gigs; a lot of our friends play in bands. Some friends of ours have recently set up a bit of a record store in Sydney, so I’ve been helping them out with getting stock. Shout out to Prop Records in Ashfield. Aside from that, I babysit my niece and nephew at least once a week. Today, I went to visit my mum—just the usual family stuff.

TIM: Really just Jiu-jitsu and cycling, and work a lot. I’ve got a pretty big yard, so I have to garden a bit. That’s about it. I try and keep it simple. Sometimes I can let hobbies spiral [laughs].

RAVI: For a while, Tim and I were playing online chess against each other constantly, all day.

[Both laugh]

TIM: I like letting new hobbies in because I love to dig through information. I have to edit down and be tight. I also played Dungeons & Dragons, with some friends.

Find OSBO’s EP HERE on Blow Blood Records. Find the demo at OSBO’s bandcamp.