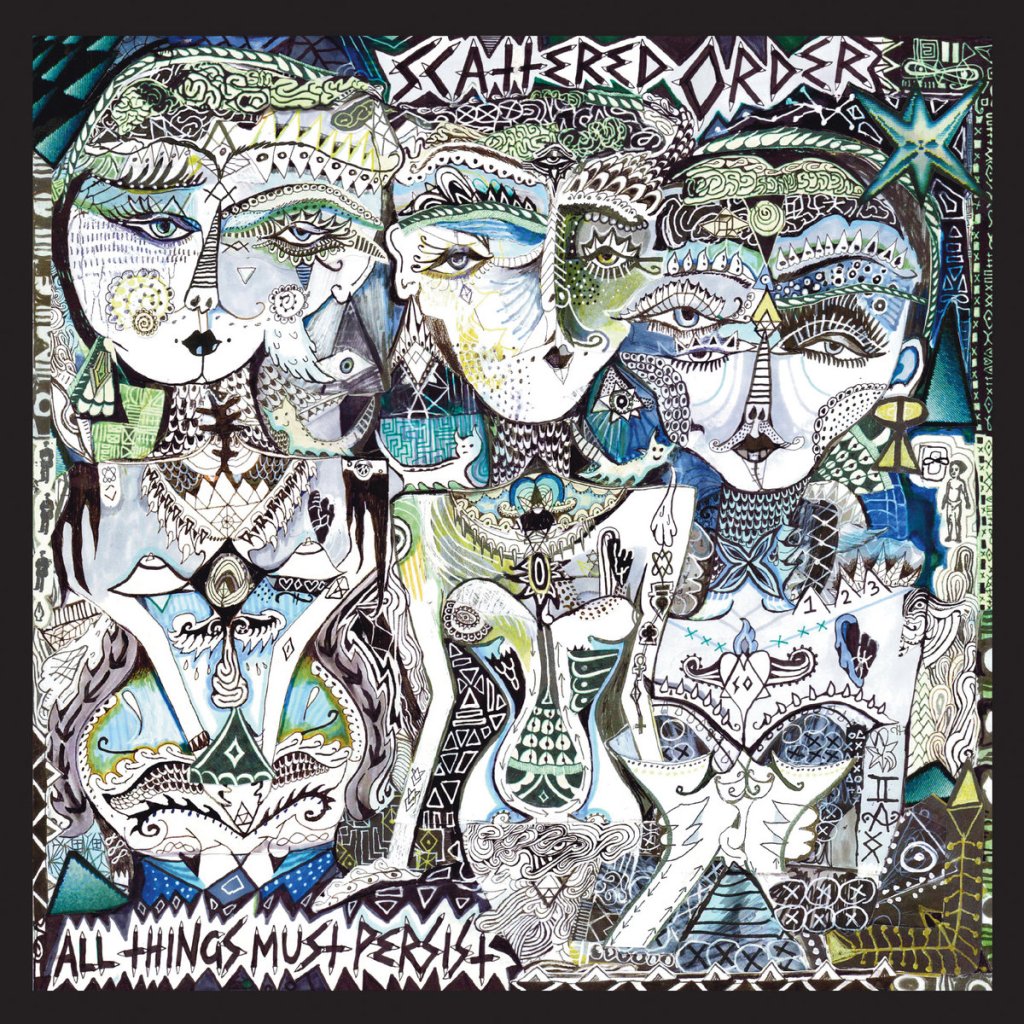

Scattered Order emerged from Sydney’s vibrant post-punk scene in 1979, founded by musician Michael Tee and sound engineer Mitch Jones. Their inception, born from a Boxing Day brainstorming session, epitomised a DIY ethos, as they pooled instruments and gear in a small Surry Hills house, igniting a musical spark that would define their legacy. Initially part of The Barons collective, Scattered Order soon charted their own path, founding the M Squared label to explore experimental soundscapes.

With a rotating lineup and an appetite for sonic exploration, they blurred genre boundaries, leaving an interesting and unique mark on the underground music landscape. Their music, characterised by a blend of found sounds, unconventional songwriting, and experimentation, challenged conventions and inspired subsequent generations of musicians.

Their live performances, often supporting international acts like New Order and The Residents, showcased their eclectic sound and infectious energy, further cementing their status as one of the pioneers of the Australian post-punk scene. Despite facing challenges and changes over the years, and a resurgence of interest in their music in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Scattered Order remain committed to their artistic vision.

The reunion of founding members Mitch Jones and Michael Tee sparked a new chapter for the band, leading to the formation of Scattered Order Mk1. Their live performances, ripe with forward-thinking experimentation, have garnered renewed appreciation from audiences.

As Scattered Order continues to embrace new technologies and collaborations, their dedication to pushing musical boundaries remains steadfast. With a renewed sense of affirmation and optimism for the future, the band continues to create a soundscape that embodies the essence of artistic freedom.

This is why Gimmie love them! We were excited to chat to Mitch Jones recently about new double album All Things Must Persist, their process, creativity, M Squared, and more. A conversation filled with insights, and all the fascinating secrets behind the music.

MITCH JONES: Music is an emotional release for me. I’ve always liked listening to it, and I found out that I really like creating it. I like manipulating sounds, placing different things with each other—I enjoy the thrill. I was never really a trained musician. I started this journey as a sound engineer, and I’ve taken that into creating my own music. I use whatever’s to hand. Over the years, technology’s changed and I pick and choose what I want to use.

It’s good fun and it’s always exciting to make something new and then move on. You learn a little bit along the way – what you don’t like and what you do like – and you just keep doing.

After school, I went to art school, but I never really carried that on. I found music and that suited me better than art.

Did you find anything helpful about going to art school?

MJ: I met my wife, Drusilla!

Ah, so it was totally worth it!

MJ: Totally! I met some friends there that I’m still friends with. A friend at art school actually started a band and that’s how I started as a sound engineer with their band, so that all helped. It was an exciting time to live. You’re at that age where everything’s exciting and new. I can’t imagine going and doing economics for a degree or something like that.

Same. I couldn’t do anything like that either. How did you first discover music?

MJ: As a child, I constantly listened to the radio, through a little transistor my parents would be listening to commercial radio. And then I discovered, my parents had a stereo. Then I discovered you could go to the local record shop and actually buy records. I started buying things that I liked, I started collecting records and songs I liked. On TV you had (I’m showing my age here [laughs]) like GTK on the ABC. As I got a bit older, in Sydney a lot of radio stations had put on free concerts in parks. So I started to go there and I enjoy live music.

What were the bands that you found yourself gravitating towards?

MJ: I always sort of gravitated towards something weird, slightly left field, not the most popular band at the time. I found that more interesting. Maybe I always went for the more underdog status bands. When I was growing up, it was all Skyhooks or Sherbet. Where I’d rather be listening to Band of Light or La De Da’s. I avoided the top 40.

Who were the bands you’d go see live?

MJ: I was lucky because when I was in art school because punk bands started appearing. I saw amazing bands like X, Wasted Daze and Johnny Dole and The Scabs—all this in your face in small rooms, it was loud and exciting. I thought, ‘Oh, this is fantastic!’ It was immediate and exhilarating. I got carried away with it all.

Did you grow up in Sydney?

MJ: Yeah, I grew up in Sydney and went to Sydney College of the Arts, which had just started, they were in Balmain. I was doing a graphics course and hanging around the inner city so I got to see a lot of small bands in small pubs.

What drew you to going to art school?

MJ: At school, that was the only decent thing I was any good at, really. I actually went to university for a year and tried to do a science degree. I was useless. They kicked me out after a year. Then I found Sydney College of the Arts. I thought I’d enrol there and that worked out really well.

You mentioned before, that you got into sound engineering through one of your friends’ bands; who were they?

MJ: The band ended up being The Numbers, which ended up quite a big power pop new wave band. I started learning there, on the job. In those days, it was all carrying PAs around and being a roadie, but I learned sound engineering; about microphones and mixing desks. Through half of 1978 and all of 1979. That was a great education. I ended up being a sound engineer for various bands for the next 15 years.

It was good, but I decided that I could do this too. I wanted to make my own music and find like-minded people to collaborate with.

I understand that sound engineering influenced how you made your own music; how?

MJ: I approach things by finding the sound, it doesn’t matter how it’s generated. Then I manipulate it through electronics or equalisation or effects to make that sound suitable for what I want to use it for. Then I cut things up and looped them. I rely more on my sound engineering skills rather than my musical skills. I could play rudimentary keyboards and bass. I was listening to how it would sound at the end. You’re always layering sounds and getting a good mix. Even something delicate or something powerful. That was the way we did things, rather than having a group of musicians and practicing a song. It all starts with a sound and I build on that.

What is one of your favourite parts of that process?

MJ: Finding something completely out of the box, something that would go with the original sound. You have an original sound, you really like it and you think the next step is to find something that either jars against it or fits really well. That next step is what I find the most enjoyable because it could take the piece in a completely different direction. From there you have a fairly good idea where the end point could be and work towards it. It’s a surprise! When you put that second thing in and it goes somewhere you never expected it would.

You try and remain open while creating?

MJ: Yeah, always. I don’t have a pre-plan or a pre-idea in my head. With the band now, there’s three of us involved, and we all have input and none of us are sure where it will end up. We put things together, take a lot of things out, and try different ways of approaching it and the song ends up sounding like it does. Not by accident but by following the feel of it.

It’s almost like an audio collage?

MJ: That’s a good way to describe it. You’re putting things together, you put something down, you think that suits, or maybe that suits if I take something from the original out. It’s not just keep on adding, you have to subtract at the same time. You know, it might be other things that have come in, three or four steps beforehand. You might have to subtract that. You let it organically turn out the way it does.

How do you know when a song’s finished?

MJ: The way I know is I keep playing it, then I’ll go away for a few days and just not listen to it, then come back and listen to it with new ears. If it’s working, you think, right, that’s it. You need to give it time—keep coming back and thinking, is it still good? If it is, it’ll be released. Or if it isn’t, something might need to be done to it or some might be completely scrapped. We’ve got a bit of a scrap behind us in the history of this band [laughs].

I read somewhere that pulling apart your mum’s Telefunken radio with a soldering iron influenced your approach to music?

MJ: She had this lovely valve radio. It had a little speaker in it, it had this button on it with pickup, which meant you could plug in an instrument. You could use it as an amplifier. Being a stupid teenager, I had this big speaker, but I couldn’t connect the big speaker to the amplifier. So I thought it needs a wire from the radio to the speaker. Instead of just running the wire out of the bag, I thought, I’ll put a socket on the side of it, but I didn’t have a drill. So stupidly, I got a soldering iron and just burned through the plastic to make a hole completely wrecked the look of the thing. Mum never forgave me. But the speaker worked, which I thought was great.

In the beginnings of Scattered Order you were, in your words, ‘railroaded’ into being the vocalist of the band. How did you feel about doing it then and how do you feel about still doing it?

MJ: Doing it then, I wasn’t that comfortable with it. But the thing is, right at the beginning the lyrics were a little bit secondary, but then they became more important. Then, I was conveying the lyrics, no real emotion. I was speaking them off. That was fine and that worked. Then, when we got back with the three of us about 15 years ago now, we were just doing instrumentals. I just refused to do vocals. The other two were saying, ‘You should do vocals.’ And finally, I relented, but I really started to enjoy that. There’s less words in our songs now. So I’m not just reading off, like it sounded like I used to, read off a shopping list or something. Now I can put more emotion into them. I’m writing the lyrics now. It’s good. I wish I’d taken that approach much earlier, but you can’t change the past.

Do you think that in the beginning you didn’t want to do vocals because you were self-conscious?

MJ: Oh yeah! I’m still self-conscious about crying. At the beginning the other people in the band were all fairly competent musicians and were all doing other things. To justify my position, I thought, well, I’ll have to do the vocals. Come up to me these days and say, ‘Oh, I really liked it!’ But I could never remember the words and would have lyric sheets everywhere. We wanted vocals. There was no other vote. We didn’t want to go out and find a rock singer. I was chosen and I was it.

You mentioned that later on lyrics became more important to you, and that because you were writing them…

MJ: In the beginning, Dru, my partner, was writing a lot of lyrics, and I was writing some lyrics. But even the one song I wrote, I just wanted to just say it, and that was it. I was more concentrated on the actual band sound. Now, I think the vocals are more integral to the band sound. Especially on the new album, they’re more integral to the song. There’s less musical things happening to hide the vocals, where in the earlier stuff, the vocals were buried under a wall of noise.

I really love the vocals on the new album, especially in the song ‘Need to Increase Speed’. I love how at the end off the song you say ‘I. See. God.’ – it really caught my attention. I was listening in headphones and that really stood out.

MJ: That’s interring that you say that. The whole album was made in headphones, so listening in headphones is great! ‘I See God’ is a name of a track from Pretty Boffins from the 90s. The track was all about travel, travelling long distances, and crossing galaxies. It was a bit like 2001 A Space Odyssey.

It has a real cinematic quality to it.

MJ: Yeah, and especially with that lovely brass line near the end, which really lifted it. It could have been a song that could have kept on going into affinity.

Are you a spiritual person at all?

MJ: Not really. I was brought up Presbyterian. I do believe there is a God or a higher being. I’ve got the call of God. I’m not very spiritual. I just believe that people should treat people like they want to be treated. People should get along. Life’s too short to argue and get angry. Walk outside and look at nature.

Yeah, that’s one of my favourite things to do. No matter how much of a bad day I’m having, I can walk out my front door, look at the trees across the road in the park, and I feel better. It’s like it gives me a moment for a breath, a pause, a reset.

MJ: Yeah. My partner, Drusilla, and I, we live up in the Blue Mountains in Sydney.

Oh, beautiful!

MJ: We’ve got all this bushland. We can look out our back door and over this valley and it’s peaceful. It’s fantastic—all the bird life and the change of the seasons, it’s beautiful. The mountain air is really crisp. I go out there and I think, ‘I’m glad to be alive.’

I noticed there’s song titles and references from previous songs on older albums in the lyrics of the new album. In the song ‘The Silent Dark’ you say: The ‘prat culture’ of youth is now faded.

MJ: Well, that’s how I feel some days. Prat Culture was our first album. We’ were obnoxious young people, and ‘prat culture’ suited us then. But we’ve mellowed a bit. It’s good, it’s not a bad thing. It’s life—you just move on. Priorities change. You just go with it.

For readers that might not be familiar with what prat culture is; what does it mean?

MJ: We took it from Linton Kwesi Johnson’s album, Bass Culture. We really liked that album. So we thought, ‘Right, what are we?’ We were at Prats: a bit obnoxious, a bit against the grain. I don’t think we’re obnoxious anymore [laughs].

I really love all your album titles, they’re always so interesting. I really love A Suitcase Full of Snow Globes.

MJ: Dru might have come up with that. I keep a sheet of paper and write down interesting phrases from TV or talking or reading. When we need a song or album title we have something. A Suitcase Full of Snow Globes was a double album, over 20 tracks, and they’re all little sparkly gems to us.

What’s the story behind the new album’s title, All Things Must Persist?

MJ: That’s even sillier [laughs].

But it sounds so profound!

MJ: Well, it does, doesn’t it? I think Shane came said, ‘George Harrison had All Things Must Pass. How about All Things Must Persist?’ We all agreed, we all thought it was a bit of a laugh. But, you know, I’m just thinking about it now, and well, all things shouldn’t really persist; bad things shouldn’t persist. All good things should persist. It sort of suits the band, because we’re not going to go anywhere, we’re just going to keep creating music—this is what we do. We’re persisting.

Have there ever been times in your life when you didn’t make music?

MJ: There was a time when my partner and I, in the early 2000s, we went to live in the UK. Before we left, the band was virtually just down to the two of us and the bass player. We wanted to get out of Sydney. John Howard was in power and we thought, bugger that. So we went to live overseas. We thought we’d do some music overseas, but circumstances conspired against that. We were too busy working to survive, to do any. There was a few years like that and we finally came back to Australia. By that stage, there was a lot of interest from overseas labels, mainly European labels, to start re-releasing earlier material and we started putting that together. Doing that, I got back in touch with Michael Tee and Shane Fahey and we decided to try making some new music together. That was around 2008.

How did it feel for you during that period when you weren’t able to make music?

MJ: I was listening to a bit of music. I thought at the time that I could do it. I put music behind me, I’ll do something else. And I was just working crappy jobs, but I thought I was living in a new place, new surroundings, which was fantastic and all that. But I came to realise that I really needed music in my life. So, we came back and we did that. Drusilla started doing all her own solo stuff and I was doing my solo stuff. We started to get into using computers for recording and using Ableton. I found out, you don’t need need all this equipment to realise what you want to do. Technology definitely helped us to get back into it.

I love when people are open to embracing technology or whatever is available to create.

MJ: I always see it as like an opportunity to try something new. I’m still trying to get my head around my mobile phone [laughs]. We save time and the cost.

You’ve mentioned your partner a few times and it seems that she inspires you; what’s one of the best things you’ve learned from her about creativity?

MJ: So much. To be patient. Little and tiny sounds are good sounds. Everything doesn’t have to be loud and brash. Try new things. Don’t just settle on tried and tested ways. I’m in this little room in the house and she’ll be in another room and we’ll both be writing music on computers. We put music out together as a band called Lint. She’s a great influence on me, the love of my life, to be honest.

Awww that’s so lovely! I feel that way about my husband too. Who lucky are we? Do you feel like there’s any prevalent emotions or moods on the new record?

MJ: I thought it was a bit too sad, but there is a glimmer of hope throughout the whole album. It acknowledges where we’ve been as a band, it acknowledges it’s been a long journey, but it’s not the end, and it’s not this, there’s a future to explore.

The song ‘We Should Go’ lyrically seems like a sadder song.

MJ: It’s more things aren’t going well here at the moment, we should get the hell out of here. It was a bit of a warning shot, you know, we should move on. Don’t stay in this place.

What about ‘It Was A Saturday’?

MJ: That is sad. It’s all about bastard men instigating violence on women. And in a lot of cases, the only way this could be ended is, if the woman kills the man. The last line: At least she has won. Well, she hasn’t really won, she’s negated the violence but put herself in a different, terrible situation. You can’t turn on the nightly news without hearing about a woman being murdered by a partner, which is a national disgrace. It’s distressing.

Absolutely! I noticed with the song ‘I See the Old Man’ – it has the ‘I Am Sandy Nelson’ reference.

MJ: That’s an in joke from years ago. We did a song called ‘Free Sandy Nelson’. Sandy Nelson was a drummer, ‘Let There Be Drums’ was a big hit he had. When we did the song, it was the beginning of the internet, and we thought it’d be a great idea to make the contact for the band: Sandy Nelson. We made a mythical character called Sandy Nelson, gave him a PO Box and he hung around the band for 30 years [laughs]. That’s why he keeps appearing in songs.

Is there any other conceptual continuity that runs through the albums?

MJ: We keep trying to make albums that sound different to the previous album. We all try and stretch what our contributions are, to try and push it into newer areas. It’s just a general evolution really.

How did you feel like you stretched yourself on this album?

MJ: I felt really good. At first I was worried, but the more I got into it, the better I felt. I felt comfortable having the vocals quiet up front. I didn’t feel embarrassed about my singing, I didn’t feel embarrassed about the lyrics. I ended up feeling actually quite pleased with myself, to be honest.

I’m really excited to see it all live when you come up here to Queensland.

MJ: We’re only playing two tracks from the new album live. ‘It Was A Saturday’ and ‘Need To Increase Speed’.

I can’t wait!

MJ: The other tracks are so quiet, we decided it doesn’t really fit into a loud set. We’re playing a number of tracks off the previous album Where Is The Windy Gun? And one off of Everything Happened in the Beginning. A couple earlier ones too. We try and keep a loud set, because we like playing live loud!

Was there certain sound on the new album that you had fun exploring or creating?

MJ: Quite a lot of the tracks started with minimal drones – like ‘I See The Old Man’ or ‘Dust Bisquits‘ – and pianos or meanderings from Michael, which is different to what we’ve normally done. We’ve normally started with a drum track and work from there.

What do you get from working with Michael and Shane?

MJ: The joy of hearing what they’ve come up with, really. We all live in different parts of New South Wales. So for the last few albums we have worked remotely. So somebody would send an idea out, then you receive all these things back. All the time it’s a surprise to me what they come up with. It’s like, I’d never think of doing that. It’s amazing. They’ve have a natural ability to quickly come up with something that enhances things. It’s a real privilege to be in a band with them.

Are you ever inspired by everyday sounds that you around you?

MJ: Yeah. I’ve got a little digital recorder and I record things around the house or outside. I have a selection of those I could go back to, cut them up, and use them. I record bits of the TV; dialogue of old movies. I can’t just sit there with my guitar and play out a tune. I need something to start me off and it’s normally a household sound.

Do you have a favourite old movie?

MJ: Get Carter is really good. It was on TV a few days ago. I watch the silly afternoon movies. And there was Hell Is The City with Stanley Baker, is a nice black and white thing from the early 60s, set in Manchester. I like British movies. I like noir movies. I drop off mid-70s, my interest wanes in movies. So, I really like anything from 1940 to 1975, if it’s noir. British movies too; I like kitchen sink dramas.

Do you watch much comedy? I noticed that there’s like a real sense of humour in your music.

MJ: I used to, but there’s not much good comedy around. At the moment I’m watching stupid bloody, you know, those real death things, like Buried in the Backyard.

Forensic shows?

MJ: Yeah. But comedy, no. Some British comedic game shows are pretty good. I don’t subscribe to any streaming television stuff. Just free to air TV, if it’s not on there, I don’t watch it.

Is there a particular album by another artist that had a real impact on you?

MJ: There’s heaps over the years. As a kid, Are You Experienced by Jimi Hendrix. Then, Pawn Hearts by Van der Graaf Generator, that’s the early 70s one. But then we got to the Duck Stab EP by The Residents. The first of the first three Cabaret Voltaire albums—a big influence on us at the beginning. That you can make music with minimal equipment and a small studio. You didn’t have to sound commercial, that was fantastic. Later on I got into a lot of Sound Creation Rebel and things like that. But lately, a lot of Australian bands, I really like No Man’s Land from Ballarat, a two-piece sort of bass drone-y sort of outfit. I really like the Paul Kidney experience. What else? Fables from Sydney. There’s so much good music about.

Totally. I think there’s always good music around you just have to find it.

MJ: That’s the thing you have to find it, you can go down these rabbit holes looking, I go through Bandcamp and see different things. I try and support smaller artists, that I know that are doing interesting things.

You’ve been doing that for a long time, all the way back to doing label M Squared!

MJ: Yes. There’s lots of smaller artists around the world doing interesting things. They’re all doing it for the love of it, they’re not going to make any money out of it. So you want to support people like that.

Absolutely. That’s why we do what we do as well.

MJ: The music industry has always been strange. It’s always been lots of middlemen, lots of people hustling about trying to make a buck. A lot of good artists get burned.

Yeah. Growing up, I wanted to work in the music industry because I love music. I tried it for a little but when I started to see what goes on behind the scenes and just the way artists are treated and other behind the scenes workers, it was horrible. It put me off working in the music industry. We just do our own thing regardless of the industry; it’s more exciting on the fringes anyway.

MJ: That’s the only way to do it. It happens in all levels of it, like in venues, you can tell which ones are all management-driven. Makes you think, ‘Oh, what’s the point?’ These days, they’re all scrambling over such small amounts of money, there’s no big money around.

When you’ve been recording bands over the years, is there anyone that you’ve worked with that had really interesting approaches to what they were doing?

MJ: The most interesting was when I was doing the two M Squared albums for The Makers of the Dead Travel Fast, which was Shane’s band. They were amazing. We had minimal recording equipment, they had huge ideas; together we managed to get these ideas recorded and sounding really good. They’d ended up on records that sounded fantastic. These days, I don’t know how we did that, to be honest. They’d be recording outside, using whatever comes to hand, but then juxtaposing them to a delicate piano piece or shouted vocals. The way they combined different sounds for each piece.

A lot of other stuff I recorded, there were some good things happening, but a lot of the things I ended up doing at M Squared was more around the standard guitar-based drums; a band situation. Which I found interesting at the time, but it didn’t stretch your imagination.

Is there anything that you could tell me about M Squared that people might not know?

MJ: We didn’t make any money. We left the studio owing six months back rent. For a while there, it fractured friendships between myself, Michael, and Patrick. They had left Scattered Order by the end of M Squared. Things are getting grim financially. We were all getting a bit tired of each other’s company and tired of the situation.

I guess everything runs its course naturally, and it’s time to move on.

MJ: Yeah, it’s time to move on. If we kept going we wouldn’t have lasted and it would have diluted what was happening. I look back on it, some of the releases on M Squared, I personally wouldn’t have put out. I’m sure if you asked Michael, or Patrick, rest in peace, they’d probably have a different list of things they probably wouldn’t put out. But you can’t change the past. It was great while it lasted. It had its high point. I met all these wonderful people. I’m still recording with two of them. It served a purpose in the Sydney underground at the time.

What do you sort of consider to be the high point?

MJ: The high point was when all three bands were playing: Systematics, Makers Of The Dead Travel Fast, Scattered Order. We all toured; we actually got to Brisbane. That would have been February 1982. That was the high point. Everybody was recording. Everybody had records out. By the end of 1982, things started to go down.

What was it like for you when you reconnect again?

MJ: I was good. I’d seen Patrick over the intervening years, but I hadn’t seen Michael for over 20 years! Because of this re-release business for all the Scattered Order and M Squared material, we arranged to meet up again. I was a bit wary beforehand, going, ‘Oh, what’s going to happen?’But it worked out really well. And we’ve been firm friends ever since. We’re all a bit older and a bit more mature now. We know each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Probably back then, I was too demanding of everybody. Michael was probably thought I was too much of a control freak.

Do you think that was because you wanted to get stuff done and were just excited about things?

MJ: Yeah, yeah, yeah. But I wanted to do that. I wanted to keep paying the bills as well. That helps. Michael and Pat wanted to do things, but were sort of, bugger the bills, it’ll all be all okay.

I’ve read that both you and Michael came up with the name Scattered Order, you each came up with a word?

MJ: Yeah, yeah. I came up with ‘order’ and he came up with ‘scattered’.

That makes sense, you were talking about how you were a bit more controlling back then and he was a bit more loose with things.

MJ: It does, it makes total sense.It has suited the band throughout our history because there’s always been a bit of a scattered approach but there’s some sort of order there holding it all together. It’s getting that balance right. Sometimes there’s been heaps of scattered and not much order too [laughs].

I’m the sort of person that I needs something to hold on to. I need it to be a little bit grounded, there has to be something constant throughout the song, a beat or whatever, something to hold it all together.

An anchor?

MJ: Yeah. Shane and Michael, they’re a lot more proficient on what they’re doing, and can take things further and wander around with no anchor point, eschpeially live. I can’t do that. I go, ‘What the hell is going on here? How can I contribute to this?’

You’re sort of self taught, right? How does that benefit you?

MJ: I can construct things in either simple little patterns that I could do, or if the song was constructed I could add to it. On the early stuff, Prat Culture, I was playing guitar, but I was just adding one long note every so often. I knew I could do that. I knew that I could do that live too. I knew I could do that in the recording. I knew it added to the song itself, so that was an advantage to me. Since then, I’ve learnt a bit more, but not much more. I’ve still got a guitar with all the notes actually written on the fretboard.

There’s nothing wrong with that.

MJ: I still play two or three note phrases. The whole idea is—whatever you do, however little or large, it’s meant to add to the whole sound of the track.

Is there anything that you find really challenging about creating music?

MJ: The most challenging thing is not repeating yourself. Sometimes I wish my prowess on guitar, was a little bit better than it is. But I finally come to realise it’s got to a certain point and won’t get any better. So, that’s challenging, to work with what you had and try to get the best out of it. And at the same time, don’t just repeat the last song you wrote or the last album you helped create.

That’s good advice. I know a lot of musicians can be real snobby about gear, which I think is lame. You can have the best equipment in the world, but if you don’t do anything interesting with it, I don’t really care. But each to there own.

MJ: You can write fantastic songs with hardly any equipment. If there’s emotion and heart in it—it’ll shine through!

Check out SO’s website: scatteredorder.com

Follow them: @scatteredorder and SO Facebook

Find their music on: SO Bandcamp