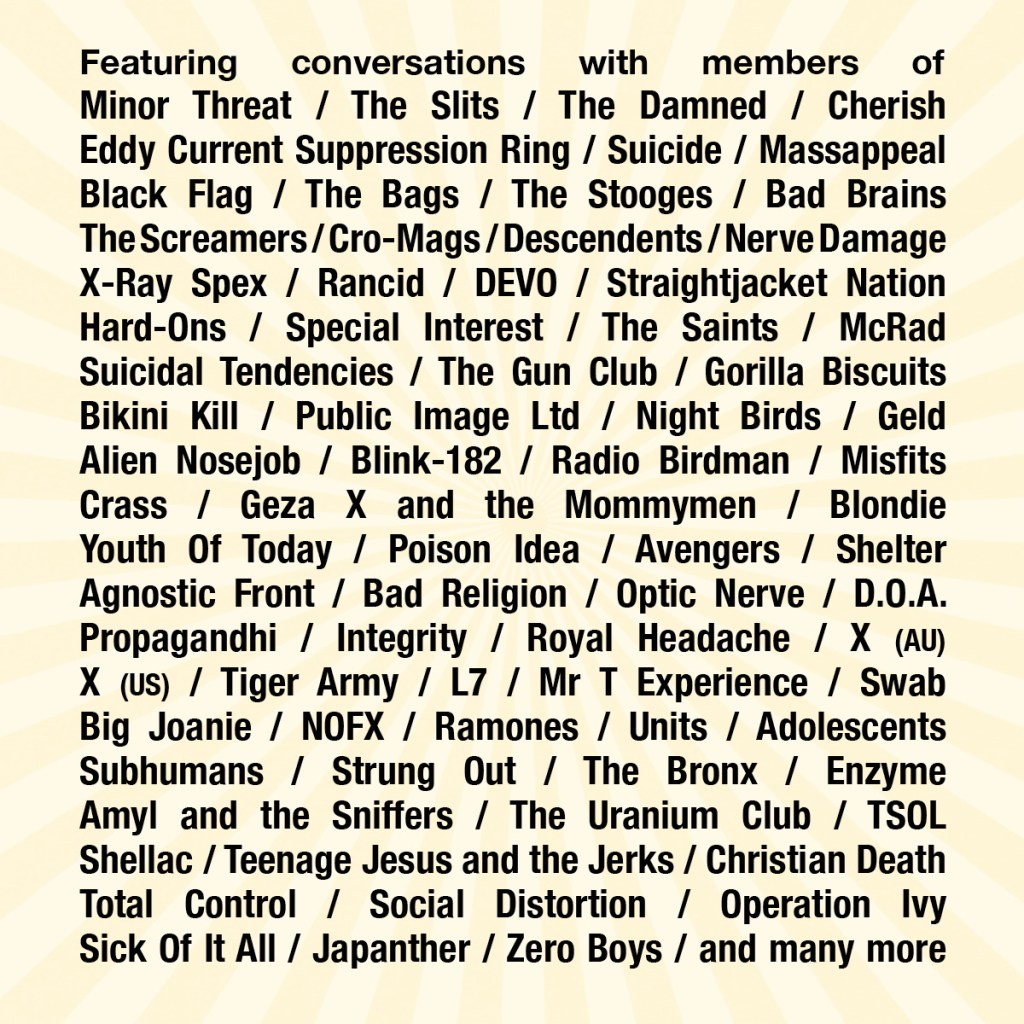

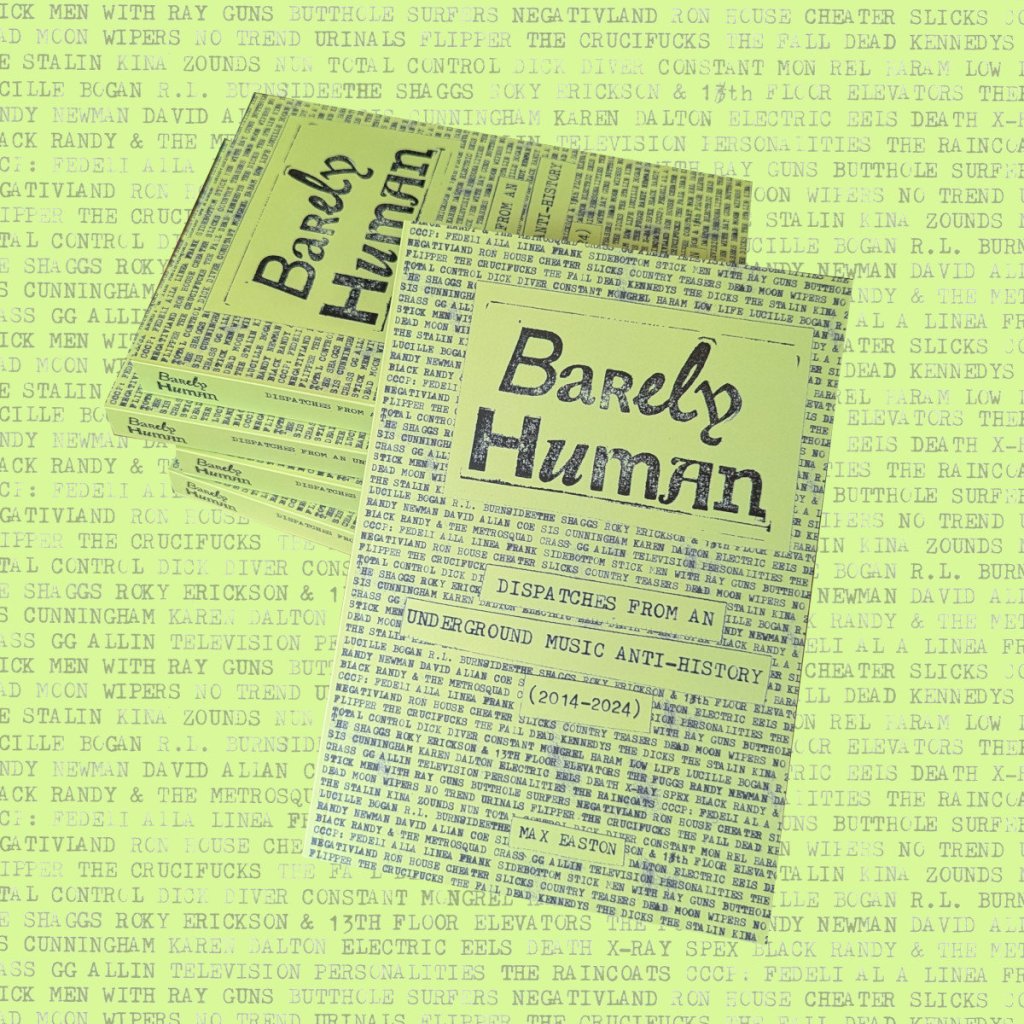

Max Easton is a writer from Gadigal Country/Sydney with a deep love for music and storytelling. He’s the mind behind BARELY HUMAN, a zine and podcast exploring underground music’s ties to counterculture and subculture. Now, ten years of that work has been collected in his self-published book, Barely Human: Dispatches From An Underground Music Anti-History (2014–2024), featuring print essays, podcast scripts, zines, polemics, and lost writing on Australian underground music and beyond. He’s also the author of two novels published by Giramondo—The Magpie Wing (2021), longlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award, and Paradise Estate (2023), longlisted for the Voss Literary Prize and Highly Commended for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award.

With a new novel in the works for 2025–26, Gimmie caught up with Max to talk writing, DIY music, and the impact of bands like Low Life, Los Crudos, Wipers, Haram, and The Fugs. We also discussed the influence of zines like Negative Guest List and Distort, along with his own experiences playing in Romance, The Baby, Ex-Colleague, Double Date, and Next Enterprise.

GIMMIE: Honestly, I don’t really enjoy a lot of music writing that’s out there. Your work with Barley Human is one of the exceptions.

MAX EASTON: That’s so nice to hear.

Your work is thoughtful and explores the underground, but it also gets you thinking about your own life by the time you’re finished listening to a podcast or reading the zine or book.

ME: That’s cool. That’s a nice effect.

How’s the year (2024) been for you?

ME: Good. I’m doing pretty good. I’ve been very lucky this year. It’s the first year since I was a teenager where I haven’t had to work a regular job. I got a grant to write a novel.

That’s great! This is for your third novel?

ME: Yeah, which is amazing because I’ve never had anything like that before. It’s been this really interesting, small-business-y type year where I’m trying to be very careful with my spending and accounts—just doing my best to make it last as long as I can. I’ve been able to write whenever I want, which has been great.

It’s also given me more time to focus on music. I’ve been working on archival projects and putting together a collection of music writing, something I’ve always wanted to do but never had the time for. I’ve even been starting bands and putting on shows again. Being free of full-time work for a year has been really, really good. I’m so lucky.

It’s like you really want to make the most of it!

ME: Exactly, because the money will run out in January or February. Then I’ll go back to work, which I’m honestly looking forward to as well. I’m going to be very grateful for this time.

Congratulations on being longlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award too. How’s that feel?

ME: Super weird! Especially with the first novel I wrote, I didn’t really realise it at the time. I didn’t think anyone would actually finish reading it. Like, I never thought anyone would get to the end.

When I was drafting it, my process was very much like, oh, maybe I like this joke in the back; maybe I should put it in the front—that kind of thing. Because, in my mind, no one was going to get to the end anyway.

Why did you think no one will get to the end?

ME: I just didn’t think there’d be any interest in it. I had never written fiction before and then suddenly locked into this book deal. It’s one of those weird things—I didn’t expect it to do much.

Even with the Miles Franklin longlisting, I didn’t know what that was. I’d never heard of the award before until my publisher was like, ‘Oh, we’ve got some really good news for you.’ So yeah, it’s been really weird to enter into the world of literature.

Especially because I was more familiar with being a blog writer or a zine writer—writing about bands I had connections with and that kind of thing. It felt strange to step out into the public and suddenly be seen as a fiction writer.

How’s the third book going?

ME: Good. I’ve got a lot of words, but the quality is not really there yet.

That can be fixed in editing.

ME: It can. I’m really impatient. I want it to be done so I can start editing, but I need to be done first. You edit as well, right?

Yeah, I edit book manuscripts. I work in publishing as a freelance editor.

ME: That’s sick. So, you’ve dealt with a lot of frail writers.

That’s my specialty. I always tell writers that they have to push through and get words on the page, even if they’re not the greatest. Then you can finesse them. But if there’s nothing on the page, you have nothing to work with. Progress not perfection, that can come later. Being a writer too, I know how hard it can be to get ideas onto a page.

ME: Yeah, it’s a really interesting mental game—trying to write, think, and navigate all the different steps and phases. I’m trying to get better at not overthinking things, panicking, or stressing out, but you can only control so much in your brain.

I saw you mention that with this book, you wanted to have a more positive view on the ideas of independence and autonomy.

ME: Yeah, because I think the second book was quite cynical. It was a satirical novel, kind of satirising everyone, including myself. It had this flat cynicism to it. The first one, on the other hand, had a kind of flat existentialism.

For the third book, I really wanted to do something different. I wanted to capture the joy of organising things and doing things with your friends—the joy of being in a band, the fun you have, and the creativity involved. Like, what happens when you decide to organise a show in a weird, unexpected space that hasn’t hosted a show before? I feel like the first two books were missing that fun side.

So with this third one, I’m aiming for more positivity and optimism, while still grounding it in reality. You know, not everything works out, and that’s okay. It’s about trying to strike that balance at the moment.

That sounds interesting. I can’t wait to read it. I’ve been thinking a lot about joy lately, especially because there’s a lot in the world not to be joyful about that we’re constantly encountering every single day without even leaving our own home. Stuff we see online, on TV, and in the media.

ME: Yeah, 100%. It’s like a very stressful dark time. There’s a lot of stressful dark information, which is very serious. And I think like we’ve got to engage with it and think about it in a serious way. But, like you said, you still have to appreciate the good things that are happening and try to rally around that instead of letting the bad stuff pull you down, which it’s just really easy to do.

We were talking earlier about having shows in spaces that haven’t had shows before. I recently did an interview with Rhys who does Boiling Hot Politician. He mentioned how his album launch show at a pub got bumped last minute for a wedding and he ended up having it in a rotunda, guerrilla-style. The Sydney Harbour Bridge and Opera House were the backdrop. He told me how joyful it was, so much so he literally hugged every single person that came.

ME: Wow. That’s perfect.

He knew of the spot because, during the Olympics, he had taken his big-screen TV there, plugged it into a power point, and watched the skateboarding with his friends.

ME: I love that. That’s real community to me. It’s about autonomy, which I’ve been thinking about heaps lately. There’s so much you have to do, so many people you have to ask permission from to get something going.

It’s often a missed opportunity. Like, we want to play a show this weekend, but we have to ask these 10 venues if they’ll let us. I miss the idea of truly doing it yourself.

A few outdoor shows with generator setups have been some of the best I’ve been to, even if they sounded awful. It’s fun. You’re doing it together, without asking anyone’s permission. It’s hard to find that kind of experience.

I felt that way watching the drain shows, especially after the lockdown in Naarm (Melbourne). Like the one Phil and the Tiles played—it looked wild and so cool.

ME: They’re awesome.

It’s the best when people come together and think outside the box and achieve something cool.

ME: We played a show at a pub recently where no one really wanted to play this show at the venue, everyone I spoke to didn’t want to be there. We all talked about how anxious the place made us feel, how we don’t really get along with anyone who runs it, or it’s just a bit difficult.

Then it was like, well, why are we doing this? It’s because we don’t have as many choices as we’d like, but I’d love to just open a pub where we wouldn’t feel so bad.

I’ve always had a dream to open an all-ages space. Being a teen in the 90s, we had a lot of those spaces. It was so cool to have something fun to do, and to be able to go to a show where people didn’t need to (or couldn’t) drink.

Drinking is a massive part of the culture for a lot of people. I’ve done a lot of interviews with creatives lately, and I’ve noticed that people get to a certain age and get stuck in a bad cycle with that, and it really starts to affect their life. Often, there’s not a lot of support for that. It can really start to impact mental health too.

ME: It’s really hard to break those habits, especially if it becomes part of how you make music. Isn’t it the same?

It’s only been in the last few years with band practices where I’d always bring a six-pack, you know, because it makes things easier or whatever. It’s just the way it is. Then, over the last few years, I started asking, ‘Wait, why?’ Now I just bring a big soda water—it’s the same thing.

Once you’ve got the habit, it’s like you’re in your head thinking, ‘That’s how you do it.’ I’m still the same. When I start a show, I feel like I need two or three drinks before I play, but I don’t know why. It’s just what I’ve always done. It’s funny, these habits we develop over time, and then one day you stop and think, ‘Why do I do that?’

As I’m heading into my late 30s, part of that is becoming a bit more cynical and negative. This year, I’ve really wanted to make sure that if I get into a negative mode, I do something to counter it. Like, if I’m going to complain about a venue we have to play, then I have to put on a show at a venue everyone likes to make up for it. I really don’t want to become that kind of complaining, older person.

Like, old man yells at cloud!

ME: Yeah, totally. It is easy to fall into.

Do you think anything in particular is impacting you feeling more negative?

ME: I’m just finding it hard to find the conditions that helped me discover the idea of DIY and punk music. I didn’t really discover this kind of music or this world until my early 20s, because I grew up in Southwest Sydney. I was trying to be a rugby league player. That was all I cared about. I liked music, but the music I liked was just whatever was in Rolling Stone. I’d buy the magazine from the newsagent, and whatever they told me was good, I’d say, ‘Oh, yes, this is good.’ I just didn’t know.

Moving into the city and going to DIY spaces like Black Wire and warehouse spaces in Marrickville was when I realised I’d never really liked music before. I realised what I’d been looking for was there.

What were you looking for?

ME: A sense of community and a sense of connection. I did access that through message boards and fandom, but there was this huge distance. The bands in Rolling Stone would never be bands I’d play in. I never thought about playing music either.

The DIY spaces were different. Within a couple of months of going there, people asked if I played any instruments because they were starting a new band. I’d never thought of it before, but I said, ‘Yeah, sure, I play bass.’ I went and bought a bass and tried to learn it before the first practice.

It was really exciting. It changed the direction of my life.

I think about Sydney now, though, and the lack of all-ages DIY spaces. How would someone discover that now? It’s like going back to this idea of the band on stage, the punter off stage. The band is ‘king’, and you are watching them.

That’s sort of informed a little bit of negativity over the years, but like I said before, I really don’t want to get bogged down in that. I want to build something so people can discover this stuff on their own.

How did you feel when you first realised, I CAN play music or I CAN be a part of that?

ME: Just happy. It was that simple. It was happiness. When I moved to the city, I didn’t have many friends, and I didn’t really understand or believe in depression or anxiety at that time either. It was the late 2000s, early 2010s – it wasn’t really a conversation.

But playing music, having scheduled band practice every week, planning how to play a show, how to record – it really gave me a lot of meaning. Especially since I couldn’t play rugby league anymore. I missed that teamwork aspect, the purpose of going to something two days a week. Music gave me purpose again.

It also opened things up. Because I could play in a band, go to a show, organise a show, and then start talking about worldly political ideas I’d never been exposed to before. I was really just a centrist, working-class guy who voted Labor and thought that was it – that’s all he had to do.

Punk taught me to think more critically, to consider all the intersecting ideas in the world. It opened my world so much.

Same! What compels you to write underground music histories with your zine and podcast, Barley Human?

ME: Like you, I had written in the past. When I started writing for stress press, it was mostly to get free CDs and gig tickets. Then, discovering punk, I realised there was a purpose – telling people about the stuff you’re seeing rather than just mooching off the industry. It was about finding the connecting elements between all these small scenes in the cities.

Eventually, it turned into more international history stuff. Like I said, I discovered punk in my early 20s, and everyone else already knew the references to all these bands. I didn’t know who Crass were, for example, so I’d have to look them up, research them, and figure it out. I learned about anarcho-punk, then had to dig deeper into these worlds.

At the time, I was doing the work for myself. I thought if I could use that research as a primer for others interested in the scene, it could help people who don’t know all the main names. It would make the transition easier.

Even with some less positive bands, I think it’s important to understand why people are interested in figures like GG Allin – the positives and negatives. He’s a very present cultural figure. It was cool to wrap that into a story or explain why X-Ray Spex and Crass were so influential. Why were they cool? Why are these people interesting?

That’s cool you do primers. In my experience of punk culture, there’s often times people can be very pretentious and clique-y and condescending to people because they might not know whatever band. Not everyone can know everything. I’ve always hated that elitist attitude and the ‘I’m better than you’ vibe. It’s lame.

ME: As a community, it should be about saying, ‘Hey, have you checked this out?’ You should be able to explain things to people without judging the fact that they don’t know. It’s a real bummer too because everyone had to learn something at some point, right? A lot of it is a replaying of the treatment someone felt when they first started going to shows. It’s like, ‘Oh, everyone was snooty to me for not knowing all the bands, so now I’ve got to be snooty.’ But no, you’re supposed to help them in. You’ve done it, so give yourself credit for learning all this stuff, and use that to bring others through.

And that’s not even just for punk stuff, but everything in life. Life’s better for everyone when we help each other.

ME: 100%—you get it.

Being a part of the Sydney scene is there anything that you might know of that’s unique or lesser known that outsiders might not easily discover or know about it?

ME: It’s hard to say because I can’t really get a feel for what is well-known and what isn’t. I feel like a lot of bands do a pretty good job of making themselves known these days. But, I don’t really look at much social media to get a feel for which bands are really popular and which ones aren’t.

Is there a reason why you don’t really look at that much social media for that stuff?

ME: I mean, I do look at it, but I don’t really get a feel for it, you know? My favourite band in Sydney right now is my friend’s band, Photogenic. They’re so good. I feel like a band like Photogenic deserves a little more recognition. They’re the best band in town. They taught themselves their instruments not that long ago—about six years ago. I feel like that’s a part of it too. I love their music, I love them as people, and I love the message it sends to others. It’s like… anyone can be the best band in town if you get together and try to make something happen.

I wanted to ask you about the band Low Life, because you did that episode, ‘I’m in Strife; I Like Low Life’, and I was reading on your blog, where you mentioned that Low Life are probably the band that for you, has most closely dealt with aspects of your upbringing and present. I was wondering, what kind of aspects were you talking about?

ME: A lot of it was that sort of Low Life mentality. Maybe they were the first band I got excited about in that 2012–2014 period. A lot of it was because they seemed really depressed, and the world around the music was quite violent. They dealt with stuff like childhood trauma, the resulting depression, what it’s like to be at the hands of violence, and also to feel anger and sadness. There was this mentality of coming together with people, not in a super positive way, but more about finding your way in the world, a world that doesn’t really want you there. It resonated with me, especially with the backdrop of crappy experiences. They really meant a lot to me when I first heard them and got excited about them.

Isn’t it interesting how a band can write about all those things you just mentioned that aren’t so positive but then listening to it felt like such a positive thing for you?

ME: Yeah, it wasn’t even an album track; it was a song called ‘No Ambition’ that they just put out on the internet. It was maybe one of the first songs of theirs I heard, and it really hit me. It was weird—it made me realise I was depressed. Like, this buzzword I’d seen everywhere was a real thing. Stuff like that is why I think I care so much about music. Sometimes, it just accesses a part of your brain that you didn’t even know needed accessing.

Do you feel like you were kind of going through depression at the time, partly because of the sporting injury, losing that whole community, and then moving to the city, not knowing many people—like, all those things?

ME: Yeah, that was all a big part of it. But it was also childhood stuff I’d never dealt with that I was dealing with at that time. Plus, I was really stressed with work and uni. So, it was like high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression hitting at the same time, without the language to understand what it was or how to deal with it.

I’ve dealt with severe anxiety and depression throughout my life too. I remember the first time I had a panic attack—I thought I was dying. I had no idea they were even a thing. Even when I think back to being a child, I used to get a lot of stomach aches and things. Knowing what I know now, I understand it was probably from all the stress I was going through.

ME: Yeah, when you’re experiencing those things for the first time, especially as a kid, it’s hard to know what they are. I would get anxious, and people would just tell me I was worked up. The first time I had a panic attack, I thought my childhood asthma had come back, so I went to the doctor and got a puffer. With depression, I thought it was just a being lazy thing.

But you learn and now you know better, which is great. You mentioned on your blog about going through multiple versions of the Low Life episode, and you mentioned you were sort of having a bit of an identity crisis. How did that sort of shape the final direction of the narrative? What did you learn from that process?

ME: A lot of it was because they came on really strong, which was exciting. They were this unknown band that brought a lot of people together, and people got really excited about them at first. Over time, though, it was like the realisation that, even though their lyrics were often satirical, they made people uncomfortable. The crowds were violent, and some of my friends didn’t feel comfortable going to the shows. But by that point, I’d already gotten a Low Life tattoo. I thought it was just like getting a Black Flag tattoo—this was the best band in Sydney during our lifetime, and they were playing right then.

I was reading when you wrote about that, and you were talking about how, you’d seen a bunch of Black Flag tattoos and had a lot of band tattoos yourself. But then you were like, why don’t you have any local band tattoos?

ME: We’re always so backwards-looking—always looking back to 50 years ago, and now it’s even more so. Before the Barely Human stuff, all I cared about was what was happening in the moment. But the last 10 years or so, it’s been more about trying to look back while still focusing on the present. I feel like there are lots of lessons for us to learn, but we act like they’ve already been learned, like it’s over. It’s that “end of history” feeling. There’s so much we can learn from the past and apply now in a new context.

You’ve called Barely Human an anti-history.

ME: When I was trying to outline which bands to profile, I asked myself, what’s the unifying theme? Part of it was that, if I wanted to talk about the birth of punk as a genre, I didn’t want to talk about The Clash or The Sex Pistols. I’d rather introduce it via X-Ray Spex. When I wanted to talk about blues music, I didn’t want to focus on Robert Johnson alone—I wanted to talk about people like R.L. Burnside and lost versions of the genre, the kind of stuff people usually skim over.

Same with post-punk: I thought the stories of bands like the Television Personalities and The Raincoats would be the best way to tell that story—not the typical narrative people think of when they think of post-punk as a genre. The anti-history part was to take the mainstream history, read it, and then ask, who’s being left out?

For example, when we talk about hardcore, we mention Black Flag, Dead Kennedys, Minor Threat, or some variation of that story. But Los Crudos, who came in the ’90s toward the end of that movement, represent one of the best versions of what hardcore became—a community-driven movement, an identity discussion, and the expression of personal struggle or the struggles of your background.

I wanted to pull out those hidden aspects that lie beneath the mainstream story. I’m not sure if it’s truly anti-history, but for me, it felt like I wanted to retell the accepted version of events.

I’m not sure if you experienced this when you were writing for street press, but there was a point when I wanted to make music writing my living. It shifted from writing about bands I was genuinely interested in to writing about whatever band the editor sent an email about. They’d say something like, ‘We’ve got this touring band, we can pay $100 for an interview, and it’ll be published across all these different magazines.’ And I started saying yes to that kind of stuff.

It was so depressing. There was this one band, I can’t even remember their name, but they were a huge touring power-pop band in the early to mid-2000s, and I thought their music was terrible. The things they said in interviews were like, ‘I just love changing the world with my music,’ and that kind of stuff. I just couldn’t handle it anymore.

I got paid $100, which, at the time, felt like a big win, but for what? For all that suffering? I never want to go back to that, writing about things I don’t actually want to write about.

I’ve totally been there. Almost every publication I’ve written for, except my own and when I wrote for Rookie, has been like that. I really hate the way the industry works, especially with PR companies.

For example, I have a friend who runs a podcast, and he’s been getting really depressed and worn out from it. He told me that certain publicists have said, ‘If you want to interview this band, the one you really want to interview, you’re going to have to interview these four other bands on our roster first.’ So, he’s spending all his time doing interviews with bands he’s not interested in, just to get the one he actually wants, or they blacklist him.

ME: Wow!

Yep. It makes me so angry. I had an interview set up with a band through a publicist not too long ago, but then something terrible happened. A family member, he’s a teenager, was with his friends, and a horrific accident happened and his friend tragically died. Understandably, we went to be with our family, and I had to cancel the interview. I told the publicist, ‘I’m really sorry, I can’t do this, I need to be with my family right now.’ I offered to reschedule when I could, but she seemed annoyed with me. They even asked, ‘Can’t you at least post about the show on your social media?’ It just felt so cold and transactional and heartless.

ME: Oh my god!

Yeah, true story. At the time, I had another interview lined up with a different publicist, but that publicist’s response was the opposite. He immediately asked if we were okay, if there was anything he could do, and assured me that he totally understood. We ended up rescheduling the chat for another time. He was like, ‘Don’t sweat it,’ which is the right response—the human response.

ME: Yeah. That’s unbelievable. And just the idea of blacklisting your friend for not doing all the interviews.

That happens more than you’d think. Back in the day, I was blacklisted by a promoter because I didn’t turn up to review one of their shows, even though I explained I was with my mum who was very sick in the hospital! I have so many terrible stories like this about publicists and the industry here in Australia, and my writer friends have told me heaps they’ve experienced too.

ME: I want to blacklist whoever that is. I have a very quiet, small boycott list. I will never book a show for anyone with a manager, anyone who’s a publicist, or anyone who demands a guarantee from a DIY show. There are all these things, and I’ve got a little list. I’m never doing any work for them because, when I put on a show, I don’t take a cut or anything. So, it’s like, if I’m going to work for free, I’m going to do it for like-minded people who are here to have a good time and try to bring people into this world together so we can keep building it and go somewhere with it. But the idea of what you went through with your family member—heavy stuff, like the death of a teenage boy—it’s not like a broken fingernail. It’s repulsive behaviour.

It is! This is why Gimmie exists outside of the industry and we only work with with good people.

ME: 100%! Same here.

What have been some of the aspects that you found most fascinating about underground music that you’ve discussed with Barely Human?

ME: Once I started making it a bigger project, where I was connecting different bands together, a lot of it was the connections that bands from completely different sounds, completely different cities, and worlds all kind of had similar to each other. Or the things that they’d be inspired by and the way that a movement or a kind of style developed. There’s so much in common between, say, The Fugs and Crass, which is like a hippie band and a punk band. Those ideas and notions I found really interesting, and something I hadn’t thought about until I started looking into them. Same with a lot of the proto-punk bands and the post-punk bands: they had this similar kind of response to what was going on around them and this antagonism. Or, like, Electric Eels were influenced by a poet like E.E. Cummings. It’s finding all these different connections as you read about a band, which you don’t get when you just play their music.

I really like the idea of bands coming together through time. It’s really almost a conspiracy-theory-type way of looking at the world—all this stuff kept happening through this process, and we kind of connected back to another time.

One of the coolest bits was I did a Stick Men with Ray Guns podcast episode, a documentary-style thing, and then the guitarist from Stick Men with Ray Guns emailed me in the middle of the night, a year later, saying I’d made all these mistakes.

Oh no!

ME: I emailed him back. He’s like, ‘Let’s talk to each other about it.’ And we had this two-hour-long conversation. I posted him some stuff, and he posted me some stuff, and I got a channel to the guitarist from one of my favourite bands in this late ’70s, early ’80s era.

Stuff like that is really, really cool. And you find out that, so much of what motivated those musicians motivates my friends now. Or talking to him about how they just wanted to annoy their audience, and wanted to be so loud that it made them hurt. They wanted to feel violence. It’s kind of like, the second band I played in, Dry Finish, we had to play at this pub that I didn’t want to play at. And I was like, ‘Let’s do a noise set instead of our punk set.’ It was like almost like what he was saying to me was something I said 10 years ago to our friends. I love those sorts of things.

Barely Human started as a zine series; how did you first find zines?

ME: Through the punk scene, Negative Guest List and Distort were the first zines I ever saw. It was at a time when I was discovering punk too. It was like, okay, cool, I can read what these people have to say, what’s new that’s coming out. They’d also have these historical type things. Whatever obsession they had at that time would just end up in the zine. It would be books as well.

So much of Dan Stewart’s writing with Distort was philosophy. I’d never thought about philosophy before. That was my first exposure to the big historical thinkers. Same as Negative Guest List. It was movies. Sometimes, they’d just talk about a movie that had been really influential on me. Both of those zines were super influential.

Why did you decide to shift into a podcast?

ME: When the zine started, it was with the long essays that I couldn’t get published anywhere. So it was like self-publishing these thoughts. The podcast wasn’t something I’d ever thought of.

But then this guy emailed me out of the blue and asked if I’d be interested in any audio work. They were kind of doing seed funding for new creatives, and if the podcast went well, they’d give you a deal with Spotify or something like that. So it was like, yeah, sure, I’ll do it.

The podcast did, by my standards, really well. I think about 2,000 people listened to every episode, which is crazy. But to them, it was like nothing. Still, I got it going, and it got me thinking in that way. So I’ve continued back via the zines and mixtapes in the years after that, even when it didn’t get picked up or whatever. And now I want to try and see if I can DIY it and do more episodes, on cassette.

What led to the decision to evolve Barely Human into a 300 page book?

ME: It got to the point where I was starting to think about doing a new podcast season, trying to figure out how to do it. I was going through all my old notes. Even just searching through Gmail—it’s like, I don’t know where I wrote about this band, I can’t find where it was. So I just started putting everything together, archiving all my stuff.

And then, as things go, a lot of this writing is quite old now. It’s 10 years old or stuck somewhere. You can only listen to it on a podcast, so it’s stuck somewhere on the web. I thought it would be nice to bring it all together, just to wrap up that 10-year period for myself.

Then I thought that would make sense, especially when every now and then someone emails me, like, ‘Oh, I’ve always been looking for your Butthole Surfers zine.’ It’s like, so out of print. The podcast I hear is like half of what you wrote. That’ll happen once a year, so it’s not a huge demand. But I thought it would be good to have everything in one place, in case someone wants to find some of this stuff.

So it was kind of just this idea of wrapping everything together, putting it down, and then I could move on and think about the next thing. It’s nice to have as a document.

Was there a band or artist that is featured in your book that you found had an interesting or unexpected story?

ME: Stick Men with Ray Guns’ story. I didn’t realise how dark their story was. I just thought they were a fun Texan hard punk band. That was a surprise, and to the point where I had to wonder whether I should finish writing about them too. I just started hearing about the singer and cases of domestic violence in his past. It’s like, I don’t think I should be talking about this band. But then it was kind of, well, should I not talk about it? Should I finish telling the story? It seemed important for me to finish that story.

Some of the other bands, were bands that were very present in the world. I didn’t really know much about bands like Dead Moon and Wipers. I wanted to write about them, kind of like at the start, just wondering, ‘Why are they on punk t-shirts everywhere? Why have I seen them on t-shirts everywhere, but I’ve never listened to them? What makes them so interesting?’ And I thought I wouldn’t find anything interesting. But they’re so cool. They’re like, they were two of my favourite bands after I started thinking about them, you know, and finding out the way that they made music and the way that they were so defiantly independent for so long.

I really loved reading about band Haram in your book. You mentioned on your blog that it was a tough section to write; why?

ME: Because I really wanted to write about them, it was more from the podcast, the way that that started. It started with these bands trying to provoke the FBI and the CIA, like The Fugs and their run-ins with the FBI and the CIA, and their run-ins with Crass. So, I kind of wanted to do this full-circle type thing, because their arm was tracked by an FBI anti-terrorism task force purely because they sang in Arabic, which is also something they played with in their imagery, you know, like just using Arabic script to write ‘Not a terrorist’ on a t-shirt. Then to find out that this FBI task force never translated this stuff and just the pure anti-Arabism, pure Islamophobia. The hard thing for me, writing that, which was once I was already in and doing it, it’s like, this isn’t really my story to tell. I felt like I was really writing about things I didn’t understand. No matter how I put it together, it felt like I was sensationalising the fucking horrible experiences that Nader had growing up and then as a punk musician being trailed by the FBI. I did the best job of it I could, but it was really important to me to tell that story of a punk band of today in New York getting tailed by the government, by the racist government.

Whenever we, you know, are all like a little bit like, ‘Man, it’s just so hard playing punk music in Sydney’ and like, ‘Oh, no, I have to play a venue around the corner that I don’t really like’ there’s a bigger context, like, people are being watched and isolated and surveilled.

I liked that you told the story using a lot of archival and interview stuff, so it was being told in Nader’s own words.

What have you been listening to lately?

ME: II was listening to The Spatulas this morning, they’re a really interesting DIY type folk adjacent type thing. Celeste from Zipper was in town, I’ve been listening to them a lot lately.

We LOVE Zipper! What have you been reading?

ME: I just finished the Tristan Clark’s Orstralia book, the 90s one. I loved it. It was really, really interesting, especially the Sydney stuff. f

I’m three quarters of the way through Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy, on a fiction front. It’s wild. It is so good. It’s the trippiest, it’s hilarious. It’s really funny.

I love Alexis’ work. She just writes with total freedom. What are you doing music-wise?

ME: The last two bands broke up. I was playing in The Baby with Ravi from OSBO, and the band Romance. We got our last releases out and kind of broke up. We’ve started new bands now—a band with Greg and Steph from Display Homes called Ex-colleague. We played the other night. My partner Lauren, who used to play years and years ago, has taught herself drums for this other new band we’re in with my friends. We’re called Double Date. We’re both couples. Then, starting after Witness K slowed down a bit, Andrew and Lyn started jamming, and I’ve been jamming with them as well. We’re playing our first show soon—we’re called Next Enterprise. It’s been really fun to play again!

Check out: barelyhuman.info.