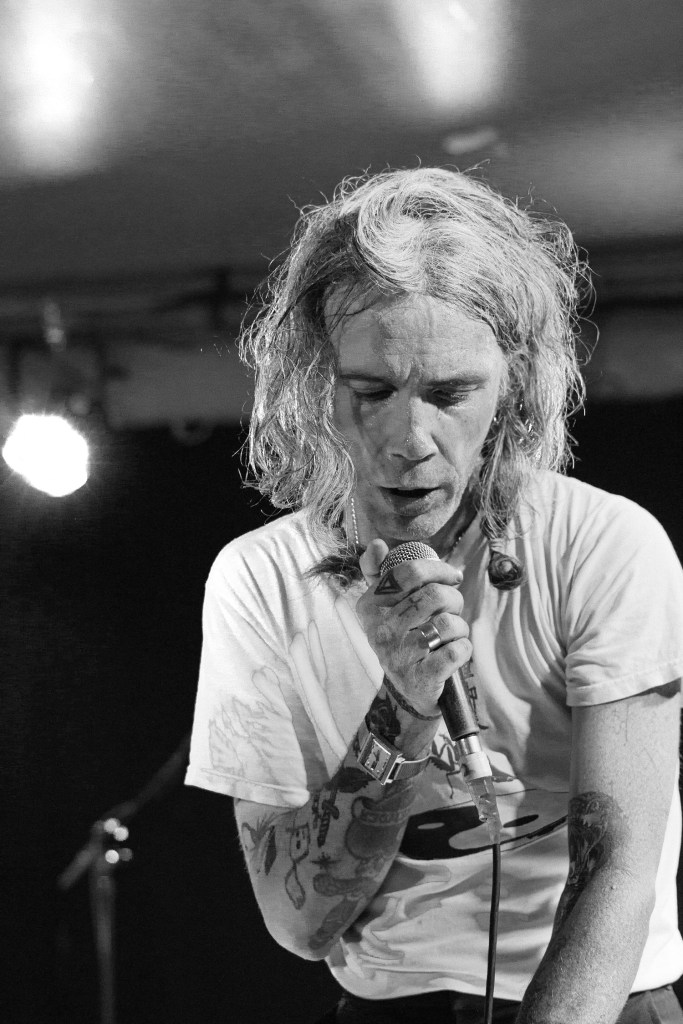

Community, vulnerability, and creativity are at the heart of Sam Taylor’s evolution—from a self-described “ignorant punk” to the electric frontperson of Meanjin-based band Fat Dog and The Tits. In this in-depth conversation, Sam delves into the transformative power of balancing strength with softness.

With raw honesty and humour, she recounts the pivotal moments that shaped her journey—from life-changing encounters high at festivals to mistakes made to painting skateboards to emotional revelations mid-performance that left her in tears and more. As Fat Dog prepares to release their stellar Pepperwater Crocodile EP and embark on an exciting new chapter, Sam reflects on the value of meaningful relationships, the courage to let go of judgment, and her ability to turn life’s toughest moments into art. Their EP has already made our Best of 2025 list!

SAM TAYLOR: I came back from tour and moved house. I was living in the middle of West End, and it was too much—too inconvenient and hectic to come home to. There was nowhere for my friends to park if they came over, and the house was really small and dingy. But now I’ve moved to Holland Park West, and I have the whole underneath of a house to myself for all my art and music shit. Happy days!

Nice! How did you grow up?

ST: I grew up in Brisbane with Mum, Dad, and my sister. I got into art and music right towards the end of high school. I was always into music because of my cousin. My sister got a guitar off him, but she never played it. I copied everything my sister did, so I started playing guitar and ended up loving it.

In Grade 11 and 12, I got into art class—accidentally. I’d applied to get into it every year but never got in. I don’t know why—maybe it was just the way the schedule lined up.

I changed English teachers because I didn’t like the way one of them taught. I really wanted to read the book the other class was reading. My schedule got changed, and I got plonked into art class. You needed prerequisites to get in, like doing art in Grades 8, 9, and 10, but I hadn’t done any of that. I had no prior experience, no idea what I was doing.

Nice! What was the book the other class was reading that you wanted to read?

ST: Jasper Jones. It’s a beautiful book. It’s amazing. A modern classic. The book my original class was reading was about cricket!

Oh, really?

ST: Yeah. The teacher had a very… interesting teaching style. Someone from head office actually came down and sat in on one of the classes to see what I was talking about. They were like, ‘Yeah, okay.’, that’s valid. And then, everything kind of worked out amazingly [smiles].

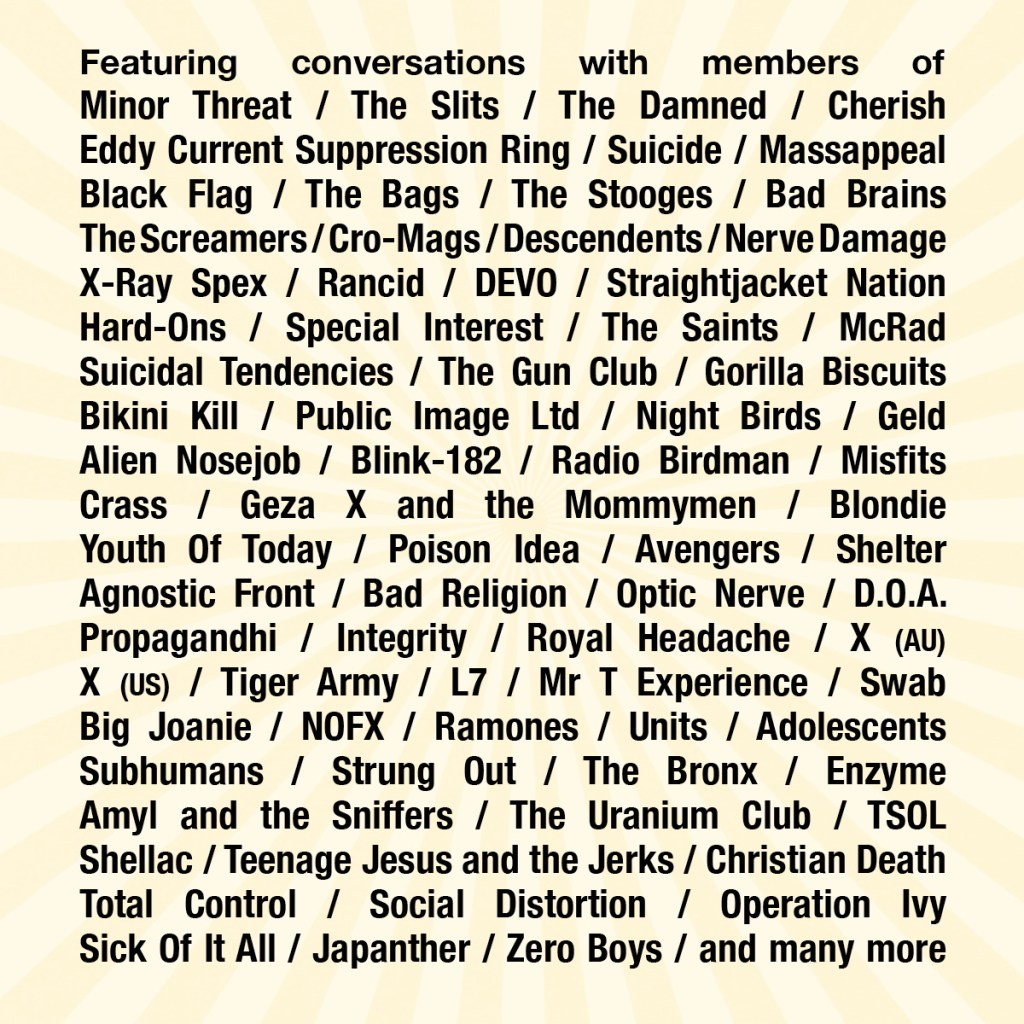

Your teen bedroom was covered wall-to-wall with images ripped out of skateboarding, surfing, and music magazines. You had posters up—Nirvana, Descendents and stuff like that. It was definitely a vibe and reminded me of my room when I was a teen. What kind of bands really inspired you then?

ST: Back in the day, I was very into heavier sort of shit—I loved Parkway Drive and all of that stuff. Nirvana was the big one for me, for my dad, he liked heaps of punk shit. NOFX was massive for me. I definitely love punk a lot.

There was a bit of a hardcore phase when I had all the posters in my room. I’d go see Amity Affliction and all that. But I’ve kind of definitely grown out of that now. It helped me at that time, very much so.

With all the skate and surf shit—Dad surfed, and he had a bunch of mates, including my godparents, who were all into skate and punk stuff. But when I really started delving into music—like, when I found things like The Cramps and B-52s—that really opened up my brain. I was like, I found my shit!

With the hardcore stuff, that was me being influenced by friendship groups and the people I was hanging out with. But once I found my shit, I went over to my godmother Anna’s house and spent some time in her record collection. She had a record player, and I was just putting on different records. I’d originally found B-52s through Mum, but when I first listened to it, I thought—fucking sick! The Cramps and B-52s were the ones that really started my brain opening, like, oh god, I really want to do this!

The Runaways were huge for me as well, including the movie—that was super inspiring. I love Joan Jett, love Cherie Currie. Even Suzi Quatro was something I learned from. Love all of that. Bikini Kill too—definitely a huge influence.

A lot of the bands you mentioned, like The Cramps and B-52s, they’re real outsiders and weirdos. They build their own entire world, and it’s not just musical—it’s visual as well, and it’s performance.

ST: Yeah. The Vandals are a really good one for that in the punk scene. When I was finding everything, I’d watch their music videos—they’ve got the funniest, most amazing, movie-style music videos. So inspiring, so funny.

Why is music and art important in your life?

ST: It’s a way I can function in this world. Whether it’s me listening to it—being able to get through whatever mood I’m in, enhance that mood, or help me feel a feeling—or doing art. Whether I’m creating through feeling or just zoning out and not having to think about things, it’s always been it for me.

Once I finally found that towards the end of high school, I was like, okay, this is what I can do. This is me. This is how I function. It’s genuinely in my blood, and it felt so good to finally find that and be like, Okay, cool.

Towards the end of high school, when you’re looking at university and what you want to do—I was like most people, wondering. But as soon as I found art and music, I thought, That’s me. Whenever I listened to music, I could see myself doing it. Whenever I saw people’s art, it didn’t make me want to create like that—it just gave me more go.

In 2014, as you were finishing high school, you thought for a brief moment that you might join the Navy, and you had an interview booked to go to. But knowing you through your art and music now, I could never imagine you doing that!

ST: I know, I know! Honestly, I was like, I don’t know what to do! I had this friend, and we were going to go to the Navy together. He went for his interview, and he was like, ‘Honestly, don’t—don’t fucking do it.’ And I was like, ‘OK.’ He went through with it for a while. Served his however long he had to serve until you can get out of it.

I’s bizarre how much I thought I had to do something. It took Mum and Dad a bit to understand that I’m not a conventional person. I’m not going to have a conventional 9-to-5 job. That’s just not happening. It did take a while for them to come around, but as soon as they were on board, a couple of years out of high school, they understood. They heard me play and saw my art, and they were like, ‘OK, this is you, and we can’t change that.’ They jumped right on board as soon as they understood that it wasn’t a phase.

Have you always enjoyed singing?

ST: Yeah, loved it. Mum had an office downstairs, and I would blast Christina Aguilera, Lauryn Hill or whatever the fuck, and literally sing to the top of my lungs, whatever I was feeling at the time—out of desperation or sadness.

You have such a unique voice. It makes you really stand out, especially with the music Fat Dog and the Tits play.

ST: Thank you. Honestly, if I could show like 15 or 17 year old me the music that we’re making now, I would absolutely shit my pants! In a good way [laughs]. Sounds weird, but you know what I mean? It’s so exciting.

We’ve got a song, ‘Should,’ and that was the first song I ever wrote back in the day. I would be over the moon to know that I’m a part of something like what I am now.

‘Shoulda’ is our favourite song of the ones you sent through from the up coming release. I love them all, but that song hits me in the feels every time I hear it. There’s something so amazing about the melody you sing, and I noticed that the melody is similar to another song, ‘Bad Boy Blues,’ that you did when you were just doing Fat Dog acoustic stuff on your own.

ST: Yes, oh my god, yeah, it was! That’s the first song I ever wrote after my first breakup ever. When we were jamming and thinking of new songs, I showed them that, and they were like, ‘What the fuck? Yes, let’s do it!’ And then, we made it what it is now. I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s crazy!’

With songwriting, I can’t force it. We have a jam, and words come to me or whatever. Sometimes there are some songs where I’ve just been like, boom. I sit there, and I write it in one go, and that’s the song. Like, it just… sometimes I can’t choose when that happens, but I love when it does.

Yeah, my friend Gutty, who taught me a lot in music, we used to have a country band called Fat Dog in the Boners. He came up to me one day and was like, ‘You should sing something about a junkyard, like being Fat Dog. I don’t know, it just seems like a program.’ And I was like, ‘Cool.’

‘Queen of the Junkyard’ and ‘Queen of the Gas Station,’ which Lizzy Grant did when she—or Lana Del Rey, when she was Lizzy Grant—was my kind of ode to that. But yeah, it just, again, just pooped out of me.

Are ‘Money,’ ‘Should,’ and ‘Junkie Witch’ all songs that you’ve written previously and then expanded on with the band?

ST: No, no. ‘Queen of the Junkyard’ I wrote for the band. It could have been either/or—it could have been for my solo project or for the band—but the way it was written, it’s definitely for the band. But ‘Shoulda’ was pre-written, and ‘Solitude’ was pre-written. I did that for my solo stuff as well. That’s probably the most recent one that I’d written, um, that I showed the band, and they were like, ‘Yeah, let’s do it.’

But ‘Junkie Witch’ was a jam because we had a friend who was… ‘Junkie Witch’ is for either if you’ve got a friend who’s obviously going down the wrong path and you’re trying to pull them out of it. Or yourself. It was both for my friend and for me too.

But that one was literally just Rob sitting there on the keys going, and then the band joined in, and then I started yelling shit. A few of our songs are written like that—purely just a jam.

As well as heavy stuff, there’s humour. That’s what it’s about, honestly we’re goofy. I’m really excited to get this music video for ‘Queen of the Junkyard’ out there.

What do you remember most from shooting it?

AT: Oh god! Everyone in the band was fucking late; not all of the extras, though. That was hectic. I remember being towards the end of filming, but I still had two more band members to bash in the clip… there was the part where, finally, the car got crushed because we had to wait right until the end to get it crushed. My most vivid memory is me on top of a tire, going like, ‘Ahhh!’ And the director was like, ‘Give it all you got, give it all you got.’ I literally almost fainted. You can kind of see it in the video—I felt myself go forward, and I was like, ‘No, no, no, keep going!’ There was only one shot; you can only crush a car once. It was such a fun day. I felt bad for the band because it was pissing down rain and they had to lie in puddles.They were like, The shit we do for you!’ [laughs]. I was like, ‘I know! I’m sorry.’ It would look really good on film. It looks amazing. Jess Sherlock and Leo Del’viaro, the Director of Photography—fucking killed it.

Every scrapyard we’d called, they were just like, ‘Nah.’ As soon as I brought up the idea—’Nah, nah, nah.’ But her dad was delivering coffees one day to a scrapyard, and then he started talking to John, who said we could film there.

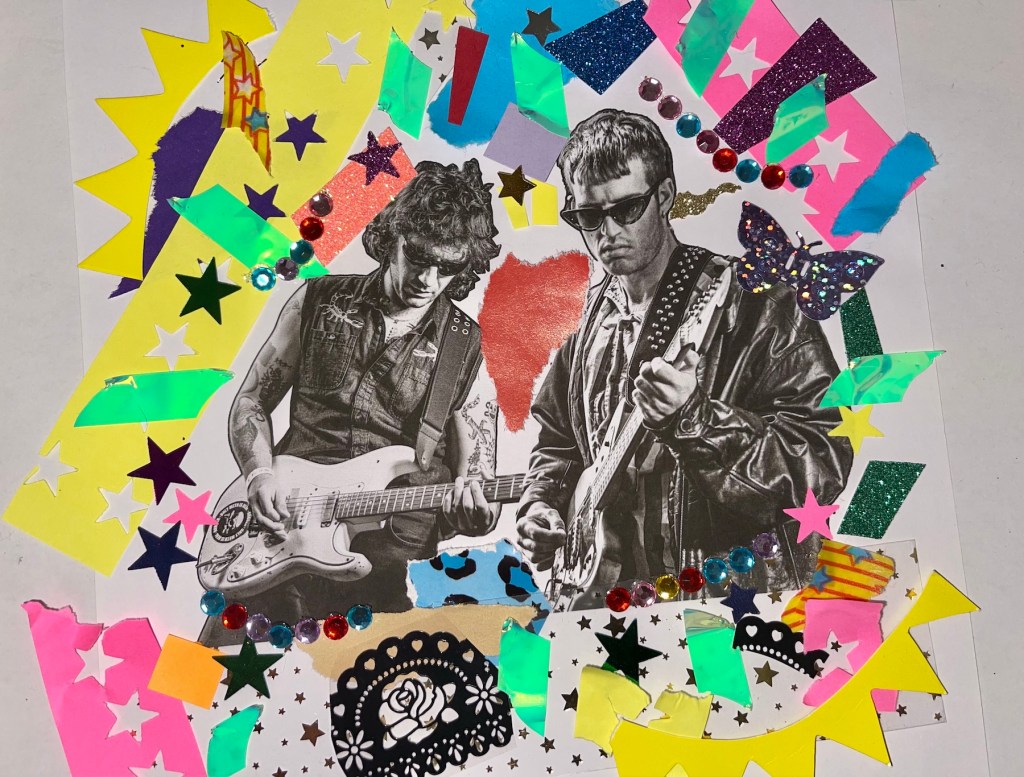

It looks great! Where did the name Fat Dog come from? You’ve been using it for a long while, for your art and your music projects before Fat Dog and The Tits.

ST: I got a t-shirt a friend gave me in high school, and it said: ‘Fat Dog Planet.’ And my brain just exploded. I was like, ‘What is that? Where do I find it? Who is it? Where? What?’ So I searched the ends of the fucking internet and everywhere I could to find it. But couldn’t. So I was like, ‘Fuck it.’ And, I won a competition with Converse to design a skateboard. I was like 17. I used Fat Dog for it. I changed my Instagram name, and everyone clued onto it straight away. Everyone started calling me Fat Dog, and I was like, ‘This is perfect.’

There is a band in the UK now called Fat Dog. They probably started in about 2021. Not mad, though, because there’s a lot of bands called Fat Dog. At first I was like, ‘Oh no, what do I do?’ And I was like, ‘Bitch, you stole the name from a t-shirt, you can’t say anything.’ Fat Dog from the UK is really good too. I love their music. We follow each other. All good, no harm, no foul.

Your first solo art exhibition was all your art on skateboards?

ST: Yeah, I mainly painted skateboards. That was from that Converse Cons pro thing I did. I got to design a skateboard, and I fucking loved it. I was stoked! The skateboarders, the crew helping, and the graphic design—it was the best. One of the skaters, I think it was Andrew Brophy, saw this little draft sheet I had with all these fucked up drawings for the skateboard. He grabbed it and was like, ‘What the fuck?’ I ran around showing it to everyone, thinking, ‘Is this me? Am I becoming me right now?’ Oh my god, it was really cool.

I noticed in a lot of dicks and vag in your art; where’s that come from?

ST: When I got into the art class without any prerequisites, the teacher fucking hated me for it. She’d tell me I’d gotten unfair treatment and made things hard for me. She’d come up behind me and say, ‘Your people look weird. Do you even know how to hold a paintbrush?’ She was a proper cow, to put it nicely. Really mean, and made me feel like shit. So, I started drawing all this messed-up shit, just because we could. At first, it was a fuck-you, but then I kind of liked it. The reactions I’d get—whether positive or negative—didn’t bother me. I wasn’t trying to offend anyone, but I did like pushing people’s boundaries and seeing how they reacted. Not physically, but mentally.

You’ve done art for Woodford. You always seem to have interesting things on the go.

ST: Yeah, I was working for Screen Queensland just before we went on tour, but now that contract’s ended. I’m not sure what’s next. But I love that kind of work—it suits me. It’s way better than doing the same thing over and over. I genuinely get depressed, my heart hurts, my stomach aches, and I get all anxious if I can’t create things.

It’s hard when you’re stuck within these little boundaries. It’s nice to poke out and see what happens and the reactions. People feel something, even if it’s just a little ‘oh.’ It doesn’t matter how they feel—it’s about stepping out of that cookie-cutter mould. Breaking free from that feels really good.

I know you like a lot of different music, besides the punk and hardcore we’ve talked about I’ve seen you rock a Beastie Boys shirt and also a Crowded House one. I know you like reggae too. It makes sense you’re in the band you are because Fat Dog and the Tits have a real eclectic mix musically.

ST: ‘We’re specialised in genre-bending!’ People ask us what we are. I used to say doom-funk-cunt-punk. And Rob’s like, ‘It’s not that.’ He fucking hates it when I say that. So I stopped saying it [laughs].

I was like, ‘What are we? What would you call it then?’ And he’s like, ‘Contemporary Australian rock.’ And I was like, ‘Shut the fuck up! No, I’m not. What do you mean?’

Then we kind of recently came up with the idea of junk rock, which is like jazz musicians playing punk rock.

You’ve been recording over the last year?

ST: Yes. Milko, our bassist, he recorded, mixed, and mastered everything. It’s completely in-house. It sounds exactly like how we fucking sound. He is an absolute genius. He’s a very smart, amazing man. I think it sounds, honestly, fucking amazing.‘

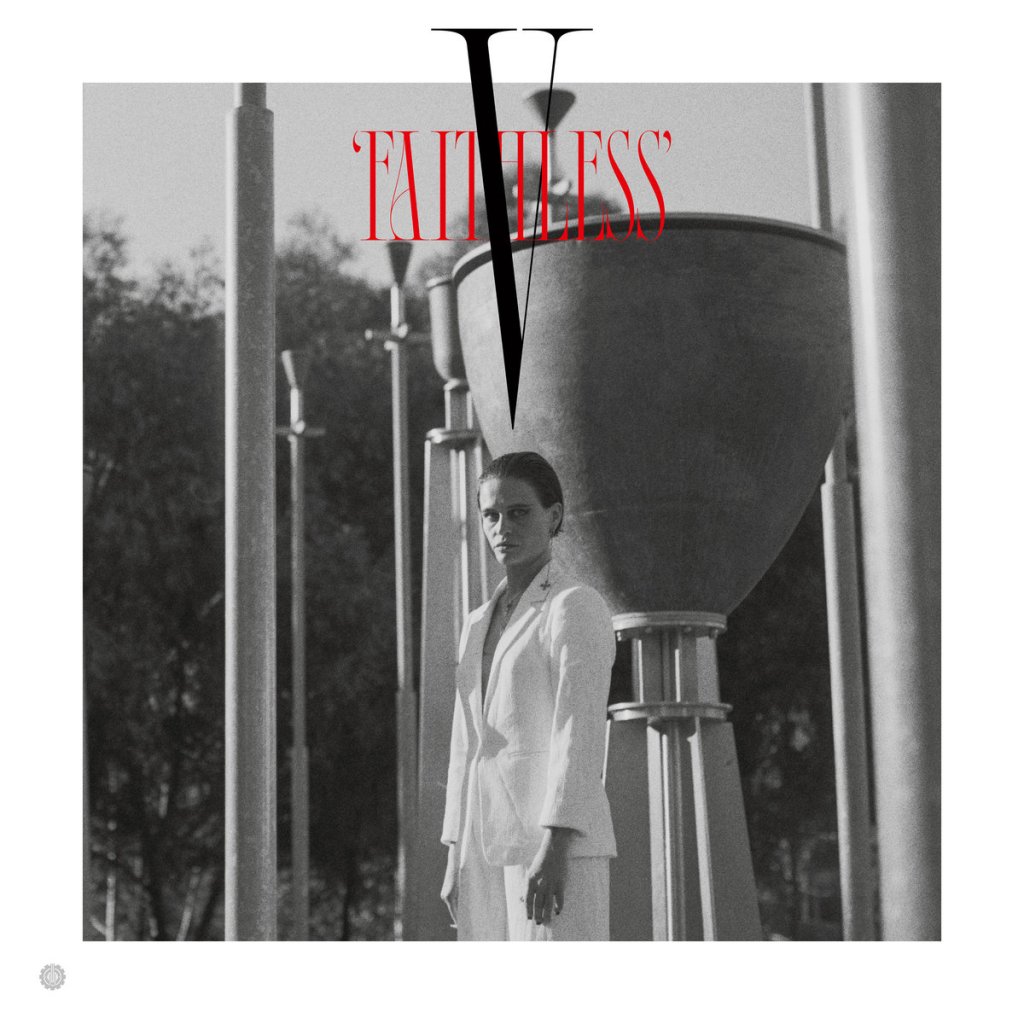

We’ve heard four tracks from it, which totally do sound amazing! How may songs will the final release have? Will it be an album?

ST: We’re in debate about that now, because we’ve got a few old songs that we used to play, like ‘Nancy’ and ‘Desert Dog’, which we’ll still play.

There’s a few older, slower songs we had recorded when we originally did the album, and it didn’t go as well as we wanted it to. We weren’t ready to record, basically. We were trying to jump the gun. So we’re thinking of releasing a five-track EP called Pepperwater Crocodile. Can you tell how high we were when we came up with that? [laughs]. Although, I’m pushing for a double-sided vibe. One side as the five-track EP, and the other side with different vibes, like doing a split EP with ourselves as, Sammy Taylor and the Brake Failures, that’ll have all those slow songs. I don’t know, though, I’m not sure where we’re at with that. Seven people in a band can be hard.

Tell us about the song ‘Solitude’.

ST: When I wrote it, I was coming out of being really sad—I went off the rails a little bit. I had to move back with my parents, they live in Kawana on the Sunshine Coast.

I sat at the beach, I took my guitar to this little spot where I always sit. I wrote it as a reminder to myself. Like—When the sun doesn’t shine like it used to, when your mind doesn’t operate like it should. When the sky turns a different shade of blue, all I needed was solitude.

I’m very much a social butterfly. I can get so carried away in that. I’ve learned better now, it’s an ongoing process.

The song was a reminder that when it gets shit, it does get better. And you can spend time alone and get through it. Or, you don’t have to do it alone. But sometimes, for me, solitude really does fucking help. Coming back to being grounded. I’m a bit spiritual, so reconnecting with all of that. Just fucking breathing and being with the moon, the ocean, and the earth.

Yes! You’re talking my language. I totally get that. Do you feel like you went off the rails in part because the subcultures and social aspects of skateboarding, the art scene, heavy music and punk communities are places where people often gravitate towards partying and you kind of can get caught up in that?

ST: Absolutely. And when something happens, or you’re stressed, or even just after a hard day at work, and you’re like, fuck, I can’ t wait to get home and smoke a bowl, or fucking drink beer…Or, you know, it’s like, can’t wait for the weekend! You don’t give a fuck about the whole week; you’re a zombie, just living to go out.

That’s what the ‘Solitude’ song is exactly about—you just need to come right back to centre and notice all of these energies and things that you’ve collected over time.

What is yours? What are you feeling that is actually fucking yours? What do you want? Or do you just get persuaded so easily? Who you’re around and what you’re around can really affect your psyche and how you deal with things. It’s like, ‘Well, fuck it, I’ll just go out with them!’ And you don’t actually deal with the thing. You think you’re dealing with it, but you’re not.

100%! Do you find that you get more of a buzz now from doing your art and music?

ST: Absolutely! Towards the start of the year, I was off it. I was not drinking, completely sober. We played a show, and the energy was fucking insane. I felt like I did the biggest line of cocaine, but it was natural energy that came from me. It felt so good; it felt so pure.

It was a show at The Bearded Lady. There was a lot of our regular crowd and friends—it was really sick. I could feel everything and see everything. Like, holy fuck!

It’s almost daunting, in a sense, because I’d be so used to at least having a couple of beers before a gig, like at very least, you know? So it’s nice. Honestly, it was really refreshing to see that I don’t need anything to do what I do.

I saw at the very first show you ever played, it was just you by yourself, playing acoustic guitar and singing. You got so nervous, your hands started shaking, and a friend had to get up with you and play guitar.

ST: Yeah, I was shaking so much! I’d rehearsed the song, but I actually could not fucking do it. I was so fucking scared. I’d never wanted to do anything more in my life, but I was so genuinely afraid.

Especially with solo gigs, I still get nervous getting on stage. Even the first time with the band it was like that—oh my God! Even though I wanted to do it so bad, there’s the other side of it where it’s like, this is everything, you wanted to do this, but I don’t want to fuck it up. I was almost fucking paralysing.

Having seen you play, I would never have guessed you get like that.

ST: Before the floods happened in Lismore, I thought it was going to flood up on the Sunshine Coast. Everyone was feeling super anxious at the time. I remember posting, I had a Bob Marley song playing, and I was dancing. I’d been painting a commissioned skateboard while watching the water come up into the house, and I was just like, oh fucking fuck! Feeling super anxious. So I posted to, number one, make me feel a little bit less anxious and maybe be able to talk to people about it. But, number two, also do the vice versa and be like, hey, if anyone’s feeling anxious, I’m pretty sure we all are—everything’s a bit weird right now.

Then I had a few responses, people were like, oh my God, you get anxious?. Believe me, I’m in my brain, I’m one of the most fucking cripplingly anxious people ever. But, because I go outward instead of inward—I appear very boisterous and really loud and weird.

You seem like a vibrant creative, really individualistic person, also someone that’s really caring and compassionate for those around you.

ST: I love dogs so much. I have seven dogs tattooed on me!

I didn’t get through the whole spiel about when I got the Fat Dog Planet shirt, but when I got it, my brain exploded, and I saw my vision.

After my music and art career, when I’m ready to settle, there’ll be a three-level house thing. The bottom level will be an animal sanctuary, starting with dogs and birds. Easy stuff, probably near the beach, but in the bush.

Second level will be an op shop to help fund it. If you’re First Nations, experienced DV, or facing homelessness, or feel disadvantaged in any way, you come in, get what you want, and you’re good to go. You can also hang out with the animals—pat them, chill with them, whatever.

And then the top level will be a skate park venue. That’s the dream, the goal, the vision. But later. I’m busy right now [laughs].

It seems like everything you do is community-based and collective.

ST: I always want to keep that as a huge part of it. Solitude is important, but community is just as important. Life gets very sad very quickly without it. It doesn’t have to be a huge community, and it doesn’t matter who’s in it. It’s about what you can do, what you can make, and how others can be involved.

It’s important to remember, we can always contribute something.

ST: Yes, exactly. Because some people, you know, you’ll think that you have nothing, so you’ve got nothing to give. But it’s not only monetary things that have value. That’s fuck all in this grand scheme of things.

Sometimes it’s just even having a conversation with someone or listening to someone. People crave that companionship; they need someone to connect with.

ST: Yeah, absolutely.

Have there been any moments that have really helped change your life?

ST: Oh, yeah, a few. I’m having a wave of memories flash in my brain. I feel like there were a few moments at Woodford when I was in my really ignorant punk phase. I remember I went to the planting, first of all. My friend and her mum took me there kind of like a, ‘You need this,’ sort of vibe, like, ‘You’re a little ignorant motherfucker.’

I went, and I’m sitting there like an old punk. And that experience kind of cracked me like an egg a little bit—opened my brain a lot.

I came from a bit of a judgmental background, had that attitude ingrained in me. I was very standoffish and didn’t give people a chance. As soon as I did, I learned so fucking much, honestly. It cracked me like an egg.

I used to be a bully. Like, in high school, I was a little fucking asshole. I was a worse bully in primary school. When I got to high school, people started fighting back. But I don’t remember anyone turning around and saying, ‘Why the fuck are you doing this?’

And one day, I was just like, ‘Fuck, why am I doing this?’ It just broke me. I went from like, ‘Fuck you,’ to, ‘Oh my god, what am I doing? Why am I fucking doing this?’

I was bullying my best friend, Angie, at the time on the internet. She was like, ‘I’m about to call the fucking cops on you. Like, why? What are you doing?’ We ended up working through that and breaking it down. I learned a lot from that. After that, she gave me the Fat Dog Planet shirt I told you about.

And then that led you into doing what you do now and being called Fat Dog?

ST: Yeah, I’ll spare the details, but we got there eventually. It’s amazing the connections that you can have if you let them happen.

School was hard for me, and I always felt like I had to be the tough girl because I got bullied a lot and I wanted people to leave me alone. I always felt I had to have a harder exterior. But as I got older, I found that there’s a real beauty in softness.

ST: Absolutely. There’s a time for toughness, and that can get you some places, but a lot of the time, that vulnerability—when you let that happen with people—is so magical. It’s so beautiful. Like, I love so much when even something as simple as walking past someone and smiling at them. That softness can be so valuable. There is strength in softness. It took me a very fucking long time to learn that, but I got there.

What are you most looking forward to in 2025?

ST: Releasing the EP! We’re going to do a proper Australian tour and then head overseas. I know we recently celebrated our second birthday this year, but that’s as a playing band. We’ve actually been together for like three years now. We’re all absolutely gagging for it. We’re ready to go.

What made you want to take your music from doing the solo thing to having a band?

ST: I always wanted a band. Last minute, a festival called Forest Fuzz—one of the sickest festivals that our mates ran—came up. I was doing this mentorship program with Alison Mooney, and she said, ‘Always carry a little card in your pocket with your manifestation.’ And then, right before the festival, I was like, ‘I’m going to get a band out of this. I don’t know how, but it’s just going to happen. And I’m really grateful for it.’

I played my little solo set. I cried through three songs. I still had three songs left to play, and I started bawling my fucking eyes out. I had to recompose myself, then play.

After, I ran back to the campsite, just to smoke some weed, because I was like, ‘That was hectic.’ Matt and Glenzy, the drummer and one of the guitarists in the band now, were sitting there like, ‘Hey, do you want a band?’ They’re both from Bricklayers. And I was like, ‘Yep, fuck yep!’

I love doing the solo stuff, but I always wanted to run around with a fucking microphone in a band. Having a guitar is fucking annoying. I’m a little alien, and I need to run around and do weird stuff [laughs].

What was it that made you cry mid-set?

ST: I was dating someone at the time, and I sang a song. Subconsciously, I realised, ‘Fucking nah, I’m very unhappy.’ And, it kind of hit me. That’s what the song is about. ‘Thank you for showing me that I’m not alone,’ is the last lyric, and you kind of wail that, like Alice Phoebe Lou’s ‘Something Holy’—it’s a beautiful song. I was singing the last lyrics, and I was like, ‘Oh, yeah.’It was hectic, and I was ugly crying.

You know when you’re in a relationship where people want you but don’t want the responsibility of you? Not dealing with what’s in the handbag, never cleaning the handbag out, but just fucking shoving shit in there—that’s it. That’s all I’m here for.

I’m a super, super emotional person. Art is how I process that. How I’m feeling about the situation just comes out in song. I’m just so fucking grateful that there’s a band of six other Tits that are so keen to do this with me. I would not be doing this without them. To have a literal dream come true is amazing. I’ve been spiritually and mentally and physically feeling that it’s like, strap in, it’s about to get real. If you want to do something, you’ve got to fucking figure it out—make it happen!

Follow: @fatdogandthetits and @fatdogplanet + Fat Dog on Facebook. LISTEN/BUY here.