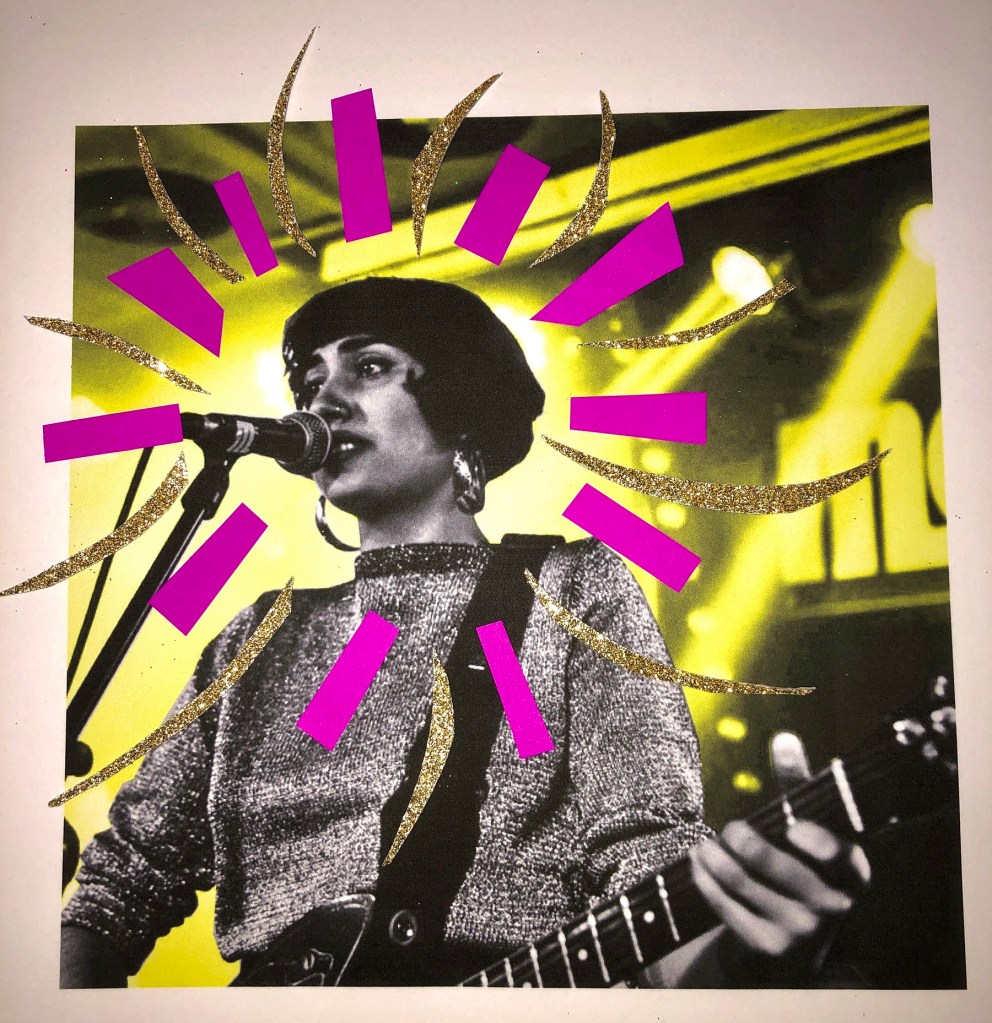

Gimmie recently caught Wet Kiss at Season Three, Fortitude Valley’s ‘weird little space for special things to happen,’ on an ordinary Tuesday night—except that a big music industry conference was in town, drawing its crowd to the usual venues. But this wasn’t part of that hustle; it was a DIY gig, tucked away from the conference crowds. No lanyards or VIP attitudes here. Just a small, dimly lit room up a flight of stairs, usually an instrument shop by day. The building, built in 1902, once housed a grocers and an oyster saloon. Now, it is packed with an all-ages crowd of people hungry for something real.

Wet Kiss is kinetic and visceral, wildly powerful, and funny. For Brenna O and her band, music isn’t just an art form; it’s a lifeline. They are sensitive souls making music for those who need it to survive, just like they do.

Brenna dives into depths others often shy away from, exposing hidden corners and bringing them into the light. She’s both a unifier and a disruptor, challenging norms in ways that make her performances crackle with excitement, spontaneity, and truth. She invites her audience to surrender to the moment, and the emotional catharsis that only sharing space and time with non-conforming misfits can evoke. The band feels bigger than the room they occupy tonight.

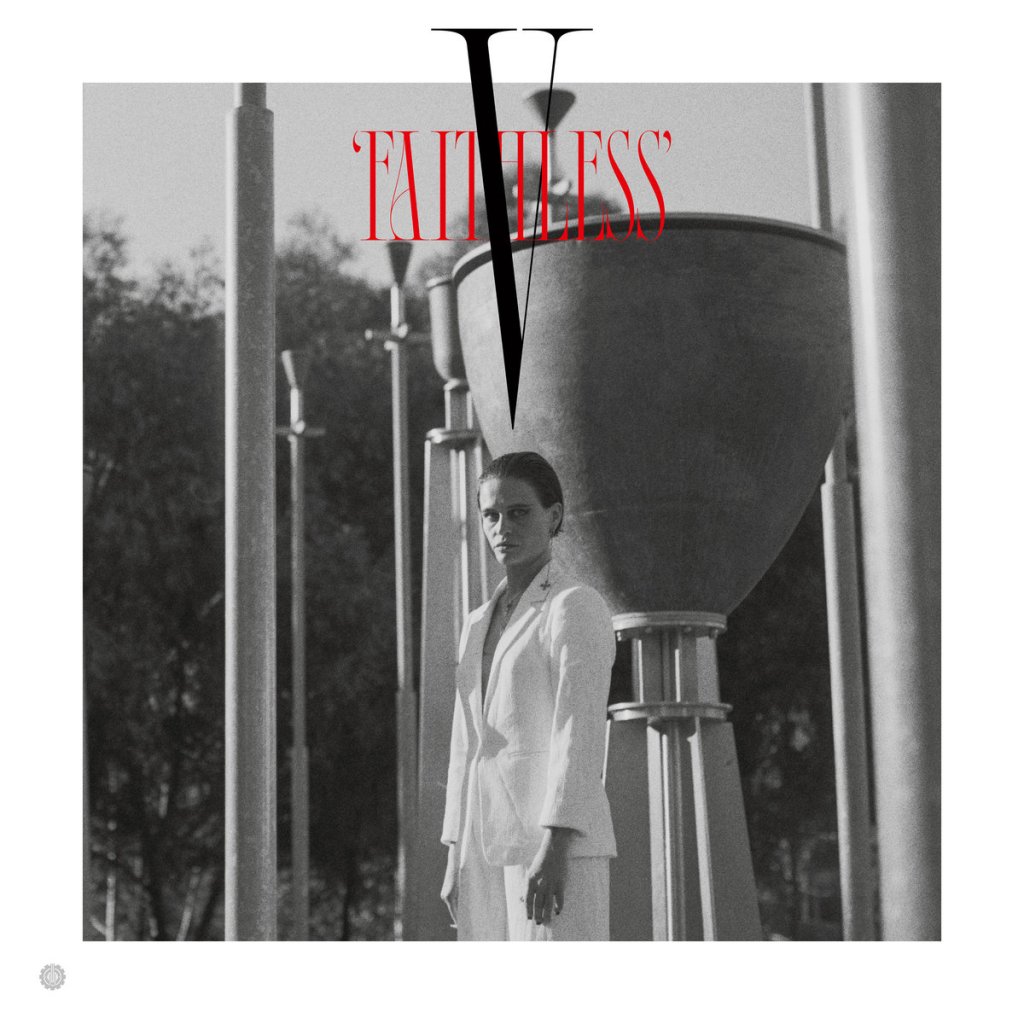

Gimmie chatted with Brenna a couple of weeks later about the band’s upcoming album, Thus Spoke the Broken Chanteuse. The album channels the eclectic spirit of David Bowie and Iggy Pop’s Berlin era, infused with the theatricality of Judy Garland and the storytelling of Lou Reed. The album showcases Brenna’s artistic and personal evolution, bringing a sophisticated writer’s eye to the fringes she moves in. She shares how moving out of her comfort zone and embracing the unknown in Berlin, helped her discover her true self and solidify her creative identity.

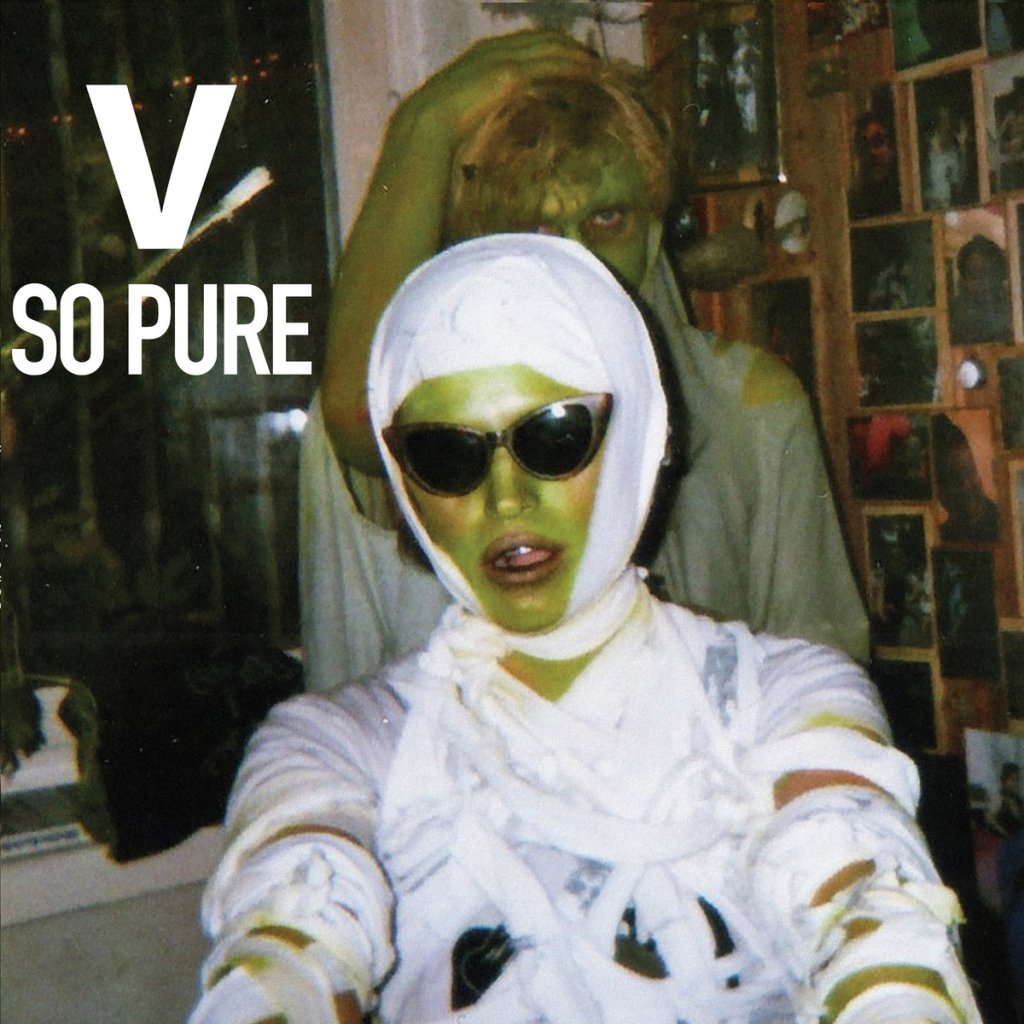

The album features anthems for the dolls like ‘Skirt,’ celebrating performance and vulnerability; ‘Gender,’ which literally touches on waiting at the gender clinic while abroad and the emotional experience, and the challenges and anxieties of navigating the more stringent healthcare requirements for hormone therapy; while ‘Small Clubs’ is about resetting oneself and living freely. ‘Chick From Nowhere’ explores stumbling out of bars at dawn, capturing the bittersweet highs and lows of fleeting connections. ‘The Gay Band’ addresses loss and memory, revealing the emotional toll of friends who have passed away, also delving into the courage required to come out to one’s parents. And track ‘Isn’t Music Wonderful’ celebrates the beauty of music and the deep connections it fosters, while also confronting the struggles of making a living in the industry.

Brenna tells us, ‘You’ve got to live like you’re in a movie.’ Each song captures that cinematic quality of life—vivid scenes filled with laughter and tears. With Thus Spoke the Broken Chanteuse, she invites us to step into her world, encouraging us to embrace the chaos and beauty of our own stories.

You’re up coming record is fire! Dinosaur City sent us through a sneak peek. It’s one of the best things we’ve heard all year.

BRENNA O: Thank you! We’ve worked hard and stayed true to ourselves. Things are good. We just played a show in Sydney at the Oxford Art Factory on Friday. I hope never to play there again. It was a nightmare.

Why?

BO: It was too crowded. I can’t even compare it to Brisbane or Melbourne, but it’s like piling people into a venue that doesn’t feel right. Intense security, a terrible green room, and only three drink cards each—we weren’t treated like stars at all [laughs]. It felt like a cattle factory.

Was the show good, though?

BO: The show was really good, and the perks were, it was incredible to have all these bands that I know from down here playing and hanging out—it was lots of fun. I’m really ragging on the venue, but… look, it wasn’t the worst experience. I’ve had worse. I’d rather play at a dingy house show that’s covered in black mould where everyone running the event is sweet to me. That’s the priority. I don’t care if it’s a big space, and it was, but it just didn’t feel great. Still, the show was fab. The next day, my partner, Dan [Ward], who does BODIES, put on a house show with Daily Toll and Spike Fuck, and it was really good.

Nice! We love Daily Toll. I’ll have to check out Spike Fuck. Anything else been happening? How’s life?

BO: My life, my life… I’m living with my partner in this room that’s, covered in absolute garbage moment, out at their brother’s house. We’re looking to move somewhere, but we don’t know how or when, and I need to get another avenue of money so I can figure out how to get myself out of this place. But it is cute and sweet and safe.

I was in Berlin for over two years, and I started coming back and forth when we were asked to do Rising. I was in a real flow in Berlin. I had a whole group of friends, and I was gigging. But after I left, things in Australia started changing, like the music scene, and there were new younger bands starting, and they were really digging us. So I just wanted to come back. It’s so nice to be around that.

You’re asking me how my life is. At the moment, I’m seeing everything through music. I really don’t know how to talk about my life without talking about that. It really is becoming very all-consuming, and because my partner and all my friends are also completely obsessed, we’re all bonding as a group over our ability to make music, share skills, and encourage each other to try and be superstars. I feel very surrounded by love at the moment. And you’re calling me and being very sweet, I really appreciate that you reached out to me.

It’s a pleasure. We’re fans of what you do. We’ve got your other album She’s So Cool.

BO: With the first release, it probably felt like it came out of nowhere. It was a bit ambiguous who we were, and every song was made with a different intention. Whereas with the new record, it was all recorded and produced in the same space. All the lyrics, all the chords—everything was laid out on the floor, and we vaguely knew what we were doing. But the first one, we were just experimenting in this old warehouse I used to live in, which gives it this disjointed, fun house kind of vibe. The whole band are all members of the band, Bodies Of Divine Infinite and Eternal Spirit, which I kidnapped [laughs]. I was doing solo things and projects before this—noise and karaoke—and it was so terribly awkward.

What initially drew you to making music?

BO: I always wanted to. I remember when I was 17, it hit me in a classroom—really, really penetrated my psyche. I didn’t finish high school because I never got very good grades and had terrible attention. One day, this person came into our art class, and he made miniatures—miniature figurines used for stage props and plotting out different scenes. It wasn’t that they filmed these miniatures, but they were a way for directors and cinematographers to figure out how the cast would be sitting and how everything would look dramatically.

It was fascinating, and it gave me a little insight into the ins and outs of a different type of career or reality. I had such a bad time in high school. A teacher—my English teacher—once told me, ‘I think you should walk across the road and file an application at Woolworths and just finish school now, because you’re never going to make it.’

They were wrong! My English teacher told me I will never ever be a writer and first year out of high school, that’s what I started doing and I’ve done it my entire life. So they were both wrong. Never listen to people that don’t get you.

BO: Yeah. They were incredibly wrong and jaded. Look at you—you have a magazine that everybody loves

It’s really nice that the people who we love and respect and enjoy their music, love and respect and enjoy what we do—that’s all you could ask for. Gimmie has become a community of people that simply love music and art, and that means everything to us.

BO: I saw Amy Taylor gave you a shout out the other day.

That was so, so kind of her. A lot of people don’t realise how much simply sharing what we do, telling people about us, really helps a little independent publication like us.

BO: She is such a stunning person.

Yeah, she totally is. It’s cool that she’s totally herself, writes amazing songs, supports and helps others. One of the loveliest people in music. Amyl and the Sniffers deserve all their success and more, they’ve worked so hard. Their new record rules!

BO: We love them! I love them. I love Amy. She’s always been so supportive of us too. We opened for them at Berghain when I was living in Berlin. The whole band came over and it was very sweet.

Why did you move to Berlin?

BO: After lockdown, I’ve always had this habit of going overseas every year. I try to save money and go—I went to New York, then Iceland, and then New Zealand, which is not as crazy, but it was very nice. Then I kept going back to Berlin. And as much as I think the place is awful in a lot of different ways, I just needed to get out of here. I had this death drive. I was dying here and needed to see if I could push myself to struggle in all sorts of ways and do something really creatively fulfilling.

That’s how I wrote the rest of the album. I went there on my own and had to make a whole new set of friends, get a job, and experiment with a new life—dealing with a new language. Now I have friends and all these people over there that I know I can go back to for the rest of my life. But other than that, there was no job, no real reason for me to go there. I had two friends who were already there, which made it a little easier.

But why does anyone go to Berlin? I think it’s just renowned for taking in a lot of global stragglers—people who are seeking an escape and a way out of judgment. Because I never really could hold down a job, and no one there gives a damn what you do. No one asks about your job; it’s almost like a dirty thing to ask.

I worked in a bar there, and I also worked for a fashion seller called the Grotesque Archive. I played shows, and Dan came with me for a year. The band joined me for a bit, and otherwise, I just did things solo. My visa is still active until September next year, so I will go back to see that out and see what happens. I’m excited; I feel like everything’s happening here for me, though.

I get that feeling. That’s so great! We’re so happy for you. It always fascinates me when people go live in a totally different place to what they know. I’ve had opportunities to but never took them up. When I was 18, I was offered a job at MTV in New York—but I didn’t go.

BO: Why?!

I’ve always been really close to my mum and she was unwell for a long time with different stuff. I’ve never had a lot of friends and spent a lot of time just with my family growing up. So to me, the idea of moving to New York, seemed like such a scary idea at the time. I didn’t know anyone, I was barely out off high school.

BO: That’s fair enough. You’re still so young at 18.

There are so many times in my life when I’ve turned down seemingly amazing opportunities. Sometimes you have these dreams, and when you’re close to getting them—or do get them—you find they’re not what you thought they’d be. You realise you don’t want that, and that’s okay.

BO: Mm-hmm. Particularly when you’re doing your creative gift, your gifted talent, and then you find yourself doing it for another institution or someone else.

Exactly. When what you love becomes tied up with industry and the machine of products and profits, it can get hard. We care about people, not products—that’s what makes Gimmie different.

BO: Yeah, that situation could be so miserable and heartbreaking. I know a lot of people that work in fashion and you have to shut off a bit of your brain. Maybe that’s your instinct that things are not right or you’re not fulfilling your creative purpose because you are so drawn to the glamour of the institution or the company.

I love fashion! But like the music industry, it’s an industry too. People and products are disposable and what matters most is the bottomline—profit. Not creativity and innovation. Obviously, I’m in favour of artists making a living, and people should do that in whatever way works best for them. However, it saddens me to see big corporations making more money—often much more than the artists themselves—from the heart and hard work that the artists put into their craft. Without the artist they don’t have shit.

BO: Yeah, it’s funny being a musician at this point in my life, not because I’ve always been super DIY, but because I now have a manager. I’m so grateful for Jordanne; she’s not industry at all. She tries to be the anti-industry. However, you have to talk to these people. She took us to Austin and South By Southwest—not to play, but to meet people. Some of them were great, but some of them… maybe this is going to get me cancelled but—just a whole bunch of people with no talent [laughs].

[Laughter]. I get what you’re saying…

BO: Trying to make deals and use the people who are creating things to get the money. I don’t know, maybe it’s a bit cliché, but it’s interesting to see. I feel like there are ways to connect with the people and the right labels that will fulfil every goal and dream you have.

When you first started making music, you were making it on your laptop and more electronically, right?

BO: Yeah, I learned when I was using GarageBand. I had old microphones from the drugstore and effects pedals that people would hand down to me. I knew this older synth musician called Matthew Brown, and he mentored me, helping me figure out the basics and tried to do shows from my studio in school. To be honest, when I was 17, I had a few bands where I’d sing and play guitar. One of them was called Total Loser Friends, and another one was called Gay, which Daphne [Camf] from No Zu, who’s passed away now. It was when we were like, maybe 18 or 19.

Those were my early band experiences, and it was this—you hear about this all the time—before you know how to play a single chord or how a song’s meant to be structured, the music just comes together so quickly. You’re so proud of everything you do, and you feel so reckless. It’s such a great feeling that you can’t get back. When you’re at a bigger level of scale, for me, you have to figure out how to manifest that thrill in a different way. You keep building it, making it larger, and get more ambitious because you don’t have that naivety anymore. Those bands were so fun to play in.

And I never had stage fright—I never got stage fright until I started doing solo laptop stuff and realised that I had no clue what I was doing. Things always went wrong. I would plug the pedals backwards, or I would use a mixer and it would blow out the sound. Or, no one came. I would have shows at the Post Office Hotel here in Coburg quite regularly to one or two people, and just push through.

It took me a while to figure out what I was writing about. It took me a while to realise, okay, you can’t go on stage unless you’re wearing heels, can’t go on stage unless you’re wearing makeup. You have to present yourself to the audience and also have a lyrical message that can be fully involved in the theatrics and storytelling.

It takes so much bravery, struggle, and learning to get to that point for me, which I guess progressed as I started transitioning. Before that, I was super awkward. I saw someone at the Oxford Art Factory who’s known me for a long time, and they said I used to be a bit more quiet. When you’re on stage, it’s like a kind of persona or extension of yourself anyway.

With the new album that’s going to come out, it feels like what you’re doing is finally fully formed. All the pieces are there, and it works. Its’ really levelled up.

BO: Thank you. Definitely. It paints a complete picture. It almost feels like a concept record or, as you said, fully realised—the lyrics, the instrumental changes, everything. I hope that they paint vivid images in your head.

The last record was, I’d have a poem here and a piece of writing there. When I was in front of the microphone recording the track, I was actually going for my phone and jumping through lyrics. It wasn’t as cohesive. It was more cut and paste—a Burroughs kind of thing, more immediate.

Whereas the new one was, I’m going to write this song, and it’s going to be like a little opus—a complete message. So I can see how it would feel more complete.

What do you see as the biggest concepts or themes running through the record?

BO: Because I moved when I wrote a lot of it—either just before I moved, or some of them while imagining what it would be like to live overseas—and some were written overseas. It’s grappling with the desire to be a star, to be successful, to transcend what I saw for a few years: stagnation, a lack of growth. I was comparing that to my physical body, as well as my intellectual growth.

What it took to make friends and try to get attention in Berlin was for me to alter myself a little bit. I bleached my hair, took a lot more drugs than I’d ever taken, and pushed myself further. The album reflects the real intense highs and lows of that experience, and my poetic take on how I felt in those moments. For example, there’s a track called ‘Chick from Nowhere’. It’s about coming out of bars when it’s daylight, trying to go home with someone, or feeling the ups and downs. It’s like cocaine—going up, crashing down. There are references to how in Berlin you don’t ring houses by numbers but by names. The chorus is sort of like, ‘Did you go to work? Did you go to sleep? I’m outside. I’ve got your name. I’m inside your place.’ It’s about looking for a certain type of friend. It’s daylight, I feel disgusting, I need to come in for a shower [laughs]. These are lived, messy experiences.

I also tried to take elements of glam rock, music often sung by men about women, and flip it—trying to be the woman they’re singing about. The broken heel running down the street, trying to get home, trying to get some money.

Another track,’Skirt’, is about this experience where I tried to play a gig solo at my friend Dan’s apartment. He’s a musician in Berlin. He suggested I do a solo set, and it was a disaster. I couldn’t play the instrument, I got really drunk before the show, and I had my leg up on the amp while telling jokes. I held the audience the best I could, but afterward, someone said, ‘Everyone was trying to see up your skirt to see what was going on up there.’ I thought, bastards! [laughs].

But then it came to me—trying to make an anthem for the dolls about performing and being vulnerable. It’s about what people are really looking at when they see a trans performer. The album has deep emotional stuff, but I’m also trying to enact a raucous, fun side.

Is there any specific emotions you mostly wrote from for the album?

BO: There’s a lot of longing in this album. The main theme I get from reflecting on it is that you can’t always get what you want. You may move somewhere, but you’re never going to escape yourself. You will always be followed by that person, by your past, by who you are.

In the song ‘Small Clubs,’ it’s about this experience of resetting myself. I’m now playing to not many people again, and I don’t know many of them. Maybe it hasn’t instantly improved my music career or my status in society, but who cares? I’m just going to do it anyway. I don’t care if people at home are telling me to come back and saying I made a bad decision. A lot of people told me I had made a horrible choice by leaving, which is so wrong.

When I left, I met great people. I wouldn’t have played with Berghain or had all these incredible experiences with Amy, or lived my life freely. At the end of the day, you’re living for yourself. You’re living for your art. So, of course, it’s good to travel. But to get to the main themes, I don’t know if there’s a lot of happiness in it. I wasn’t really feeling happy or sad; I was just trying to think super forward and become a vessel for experience. I’ve had years where I wasn’t doing that. I wasn’t thinking of my life like it was a movie.

My friend Jai, who’s the guitarist for EXEK, we became close friends in the past year. He’s always saying, ‘You’ve got to live like you’re in a movie.’ It sounds full of shit, but I just love that. That’s exactly the attitude I want to have: living for right now. I don’t think there’s any one emotion encapsulated in this album, you just have to dive into it. It’s a chaotic two years of life lived, and it seems like something out of a movie.

Let’s talk about other songs on the album. First, opener ‘The Gay Band.’ It’s a powerful track, starting with piano and your voice. It’s from the heart, and I believe you.

BO: Oh, that’s such a beautiful thing to hear! Because it’s the most important thing: belief—selling it. That’s why I love Madonna so much as a singer. Not because she has an extreme belt or anything; there are other singers I respect in so many different ways. But she’s the queen for me because she sells a message. Even if she’s singing about something you can’t remotely relate to, it doesn’t matter because her conviction makes you care.

What’s your favourite era of Madonna?

BO: I have a lot! I would probably say that the ‘Live to Tell,’ ‘Papa Don’t Preach’ era, around ’86, is my favourite. I love that whole decade—from ’85 to… oh God, I love her too much to even just pinpoint an era. But I like that. I like when she is basically herself—along with Michael Jackson, George Michael, and Prince—all those monolithic figures from that ‘80s. That’s all the stuff I grew up on. I just miss living through it, but I know it so well. That was a powerful era of Madonna, and that film she put out, is probably my favourite too. But then Ray of Light, of course.

That’s my favourite!

BO: It’s a comeback album of the century. It’s incredible.

So we were talking about conviction in delivery…

BO: Conviction! Oh my God, thank you. Because you can’t hear it when you listen to your own music; you don’t hear as much. You don’t hear conviction. I’m not listening to it and thinking, ‘What a genius!’ It is hard; it is hard to listen.

Was it hard to give that performance when you recorded the vocals for it?

BO: I did. When you’re doing a take, you’re like, ‘I have to make this work.’ You have the choice to be, ‘I could imagine if I delivered it really dry and distant,’ which can be one way an artist might do it. But to me, that’s not why I like music: to feel distant or sing like my voice is simply just an instrument padding something. I really felt it.

The themes of the songs, particularly that one, are about memories and people who have passed. I’ve had many friends pass away in the past eight years—more than I feel like I should have. And you lose something every time someone dies, but that’s not fair. I don’t want to lose anything, and I don’t want to lose people. I don’t want to lose myself. If someone dies, it’s a gift for you to keep living.

The other central themes of that song are also about confessing things to your parents and coming out.

One of the lines that really got me is when you sing about telling your parents, and they didn’t understand, and you cried. I wanted to cry when I heard that. I wanted to give you the biggest hug ever.

BO: Thank you.

It moved me because it was real.

BO: It’s really sweet of you to say. I’ve got tears in my eyes. It was about, I’m coming out and telling you, okay, it didn’t work out. And, there’s someone who I had a crush on and they’ve changed as a person and I have a friend who’s passed away, and—can I move on?

All heavy things. I love that you combined all that into one song.

BO: They all seemed related, in a sense.

Letting go of things.

BO: Yeah, totally.

Letting go of things and becoming who you are—who you’re meant to be.

BO: Definitely. When you’re writing, you have all these subconscious things; everyone has intrusive thoughts that flow through their brain. So when I’m writing, I just write down all these thoughts, mapping them out as they convey a message. I never questioned that all those messages meant something, but when you put them together, it definitely forms a complete feeling about self-acceptance and letting go.

I knew it was really deep.

BO: I didn’t even know it was that deep! [laughs]. Thank you.

What can you tell me about song ‘Metal Silhouette’?

BO: That song is punk rock and very fast. One of my favourites is Only Theatre of Pain by Christian Death. Al and I love that band. That was the one song for which I wrote the lyrics the morning of; I tried to picture different scenes and memories of intimate moments I had with my lovers or people I really had feelings for. I aimed to grab little moments and scenes, making a lot of poetic innuendos and metaphors. It had to paint quick images in your head about what you were hearing, as it was going to be a really fast song. Around that time, I was also listening to a lot of Placebo, so I was thinking about what could be the coolest thing to say in a poetic way.

Where does your love of words come from?

BO: I’m a real acolyte of Lou Reed. That’s why I feel I see lots of references, like streets and walking. A lot of his lyrics are just him walking through a rough part of New York, and all the poetry is already there for him. It’s already written; you just write about what you see.

In terms of writing, I’m also dating a poet, so we have very different approaches to how we write about things. We’re always trying to challenge each other. I guess I’m trying to write poetically, in a way, to upstage him and excite him with what I’m creating. I like the Beat poets, especially Ginsberg, and I really enjoy Patti Smith’s first album.

In a way, telling the most straightforward story may not be the right message for me. I prefer tongue-twisting wordplays that may require a second take. Rozz Williams from Christian Death, uses a lot of metaphors too.

When I’m writing, I often shuffle my sentences around in my notes. I know there’s a different phrase I can use or a totally disconnected word that can create something rhythmically exciting. That’s what I’m going for in many ways—an unexpected twist in the use of a noun or something.

However, I didn’t have any creative writing mentors who informed me. I only really started reading as an adult; as a kid, I was never encouraged to read.

Did you grow up in Melbourne?

BO: Yeah, I was on the west side and then moved around to the east with my mum. My parents split up quite young when I was young.

Did your household encourage creativity?

BO: No, no, not at all. They never did anything creative or musical. They’re not bland people at all. My mum is great; she’s queer. Basically, I was raised vegetarian, and I’m still vegan, and she’s vegan too. My dad is in the country with his new wife, and they’re conspiracy theorists—kind of like libertarians who live off their own land. So, they do have their quirks, and they like music a lot. My mum likes glam rock, KISS, and Bowie, and she probably inserted a lot of these references.

Where your love of these things come from?

BO: Yes, it’s almost embarrassing to say. Isn’t it cliché, being brainwashed as a child, and then it transfers into your adult life [laughs].

It could have been worse; at least they’re very cool references.What was the kind of music you found yourself that was your thing?

BO: The Velvet Underground and the more gritty aspects of that punk glam thing. My mum was a product of the 90s; she liked Alanis Morissette and all that kind of stuff. My parents were 17 when they had me, so by the time I was growing up, they were very set in that world. But I found myself in the 2000s, listening to the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. The music I started discovering, like Ariel Pink and all that stuff, was all through blogs. Those are the things that your parents can’t introduce you to. As a kid, I liked the Spice Girls.

I’ve got a Spice Girls record.

BO: Cool! I still do love them. I went to the CD store, and they had these multi-set collections. I didn’t know the bands; I was about 15 or 16. I picked up The Mamas & the Papas, The Cramps, and the B-52’s. I racked up all these CDs just because they were on bargain.

Those were the things that rotated throughout my teens, they were self-discovered. It was a crazy lesson to go from sunshine pop to L.A. punk and then to weirdo art student music. Those are huge influences that informed everything for me, and I saw them as very much the same things. I discovered them at the same time, and it made sense to me that sunshine pop in the 60s in L.A. would have informed The Cramps.

I like The Mamas & the Papas a lot because they convey such a breadth of feeling in one song, balancing happiness with the saddest chords. The melodies they sing, their voices, and the harmonising—even when they’re flat—are so beautiful.

I really love the melodies on your album. Gimmie have been thrashing it since we got it, and they get stuck in our heads. Like, you know how you’ll be humming something to yourself and then realise, ‘Oh wait, that’s Wet Kiss!’

BO: Oh my god! Yes!

You’re really masterful at writing poetic verses and then catchy choruses. Those hooks!

BO: A chorus should be catchy. That’s just how I think. It has to be absolutely catchy. Then you have all this space to experiment with the verses, but you don’t want them to be dull either.

The chorus of ‘Skirt’ gets stuck in my head all the time.

BO: I’m thrilled to hear this.

There’s a real attitude to it.

BO: It’s, well, you’re looking up my skirt, but like, so what? Fuck you.

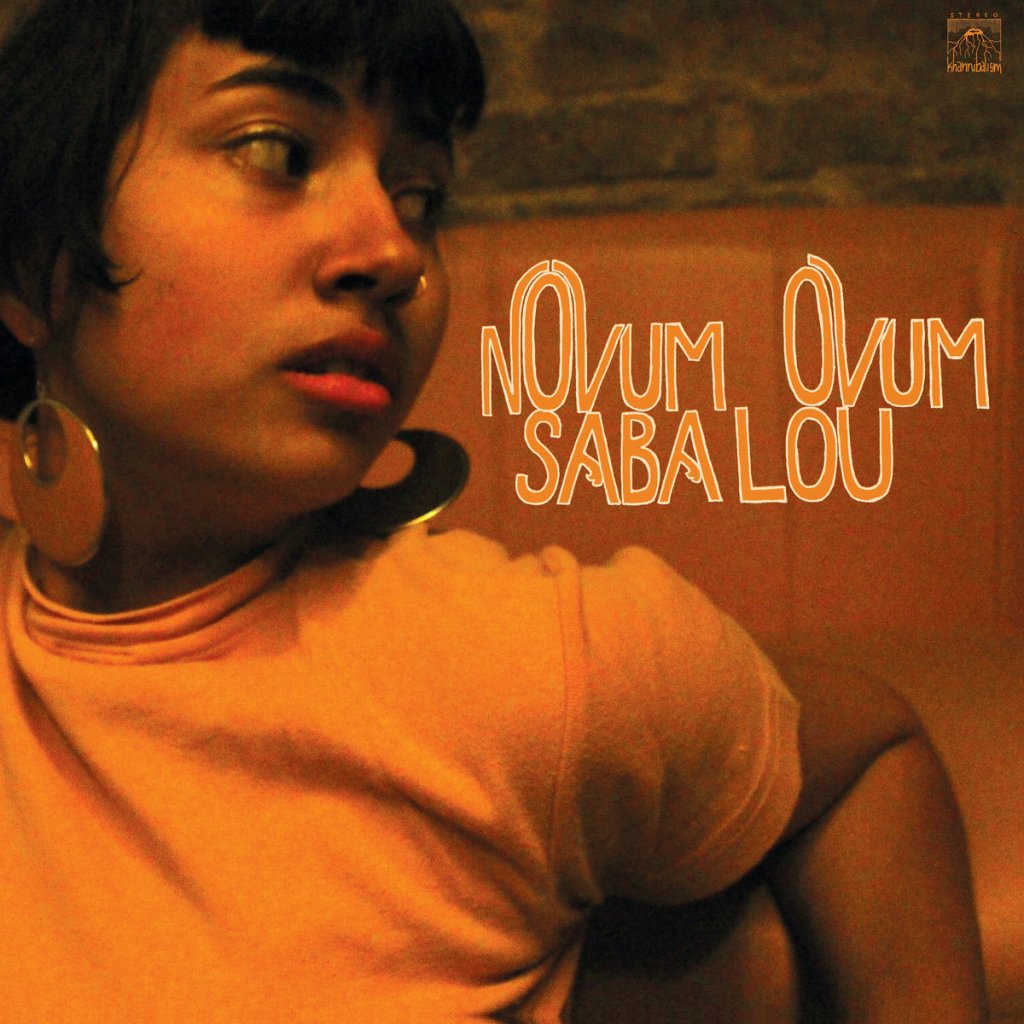

I love that. It’s a tough sounding song. ‘Isn’t Music Wonderful’ got me in the feels too? What a title?

BO: That title says it all. It’s just about how great and how beautiful music is, and how to live your life fully involved in its production, waiting for it to blossom and be loved by other people, hoping it will be. It’s about connection. When you’re writing, you’re making connections with others.

It’s also about struggling to keep making music. Like what it says in the verses: ‘Every success, another $2 address.’ Because as much as you keep playing great shows, you don’t get paid very well. The things that we all wear on stage are generally from the op shop. We keep trying to glam it up as much as possible. But it doesn’t really matter, because playing a show with the people that you love and care about—your closest friends—is a really great feeling.

Also, though, how good is it finding a $2 dress at the Op Shop?!

BO: Yeah! But maybe it’s more like a $24 dress these days, I should say [laughs].Finding a nice dress is like the best feeling in the world.

The next song ‘Gender’ seems like a significant song?

BO: Yes. That song is about waiting at a gender clinic. I wrote it when I was at the doctor in Berlin, trying to get a script for hormones because, in Germany, they don’t have informed consent like we do here. Basically, when I wanted to get on hormones here, I just went to the doctor, and they didn’t throw them at me carelessly, but they were like, ‘OK,’ after maybe two or three meetings. They wanted to know that I’d researched and understood the risks and was ready to do it for myself. But in Germany, you have to have six or eight psychiatric appointments. I was really worried.

Understandably.

BO: So I was in the waiting room, and in a situation and stressed. But at the same time, I’m like, ‘How can I turn this into a rock song? How can I make this experience reflexive, but kind of dynamite?’ I was trying to write really literally. That night, Dan was still with me in Berlin, and I made the three chords, and then we were jamming and having some wine. It came together. That’s why some of the songs are so absurdly sexual. It’s about the male unwanted attention that comes from becoming more and more beautiful.

In the lyrics you talk about adding another page to your diary. Do you journal a lot?

BO: I have a diary. I have multiple books at this point. Yeah. When I write a diary, I always say that I like to leave it on the table because it’d be such a shame for someone to open it and read my dark secrets [laughs]. I like to write it like it’s a novel. It helps me cement that feeling, which is the creative process of writing and living fulfilling your life. That motivates me.

But lately, the entries have been so matter-of-fact. Maybe because I’ve been busy—I played this show; it was good. This person played with me, I like this band, and I didn’t like this person. That has been the last few weeks of my diary entries. I don’t know why my mind is trying to get out the facts at the moment. But generally, I write long-form.

I also write film reviews. My partner has a publication called No More Poetry. And No More Poetry have a magazine called No, No, No mag. And I contribute long-form essays basically every issue where I review a film, but it’s more a diary about my life.

I’ll have to get a copy, I’d love to read that. So, in your song ‘Chick From Nowhere’ I noticed that the tentative title of the album was a lyric from that song.

BO: Yeah. Thus Spoke the Broken Chanteuse.

Where did that line come from?

BO: The ‘Broken Chanteuse’ line comes from this writer called Max, from a magazine called The Stew. He reviewed our first album and said that I had yellow teeth and called me a Broken Chanteuse. I thought he was such a little cunt for saying that. But I really love Max. Basically, I was like, wow, that’s what you think of me. But then I was like, no, this is the lore. He was building this lore and image of me based on what he thought about the music. So I was like, well, I’ll feed that back into the music: ‘So she’s got yellow teeth. She likes what she sees. That’s what it said in an underground magazine.’ I thought it sounded cool.

There’s a Nietzsche book, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, that quotes that ‘God is dead.’ That’s the book Bowie was reading during his most schizophrenic period, when he was creating his Berlin albums.

I didn’t know that. I love trivia. What can you tell us about ‘Pink Shadow’?

BO: That song was written before I went on this trip to Berlin, but it’s about the last time I was in Berlin. I was in Berlin for three months. It reflects on 2018, when I was having my ass kicked by being in such a difficult situation—struggling to get to know people and dealing with my own difficulties.

That was the first trip where I took my first estrogen tablet in Paris. I was such an egg, so undeveloped at that point in my life, while making music. I played one show in this girl-only art complex that was housed in a big pink shed. That’s why the opening line is ‘In a pink shadow in a lesbian’s bungalow.’

I was staying at this commune, KuLe, which has been around since the ’90s, where artists can live. I actually played there again when I moved back in 2022. The song is also about the experience of living with those people. I was there around the time they hosted the African Biennale, and it was really fun. I had a great time.

But it’s funny because, when the African Biennale was on, the way the European residents handled the presence of Black people was strange. There was this trepidation, like a fear of doing the wrong thing. I mean, this happens everywhere, in every country, but it felt particularly odd there. There was this weird defiance, and KuLe sits right across from a big German art institution, yet the African Biennale was just so much cooler.

It’s mentioned in the song, and other elements of the song reflect teething, growing, and figuring out how messed up Europeans can be. It’s about figuring out my life too, knowing I was going to go back, and reflecting on the memories.

That’s really interesting. ’Bunk Buggy’ is another song that always gets stuck in my head.

BO: ‘Bunk Buggy’ is the only song not about travelling. It’s about my dad. Like I said, he lives out in the country. As I mentioned, me and my mom are vegan, but he works for abattoirs—he kills animals. I don’t think he exactly likes it, but he doesn’t have much choice. He’s a very funny guy. He likes talking about conspiracies. He really likes Trump and Alex Jones [laughs]. But then he’ll oddly know who Blaire White is, a trans YouTuber who I don’t like it all. And, Catboys and all these esoteric memes. He’s a gamer. He’s a very strange guy. But then he just says these funny things. He was messaging me: I’m going to work today. And I’m riding the bunk buggy. I replied, What is the bunk buggy? He said a tractor that plows all the fields for the wheat, so you can feed the pigs that are in the pen to sustain them before you slaughter them. At the time he was getting severely underpaid and wanted me to help him. I tried. But his workplace, has all these signs about, if you complain or join a union, you’re like a communist. Crazy shit.

Wow!

BO: He has no choice out there. I guess the song is an exercise in making a different type of song. I had the funny word, wrote down all these lyrics, and then we were jamming. Before this record was even conceived, this has been a song we’ve had for a long time. I just inserted ‘bunk buggy’ as a chorus.

I was also inspired to write it after hearing this Cocteau Twins song called ‘The Spangle Maker’. It’s about a man who works in a spangle factory—those little metal spangles. It’s such a beautiful song, though I don’t think ‘Bunk Buggy’ is a beautiful song. It’s a raucous rock song.

I thought there was something about my dad’s profession and the despair of that which I could form into a song. When it comes together, I think it’s funny because, to me, ‘Bunk Buggy’ sounds like I’m trying to create a new dance. It’s not a known word, but it’s a funny phrase to say. I was trying to make it end the album with this refreshing, strange, off-kilter vibe that reflects the reality the whole record is composed of.

Is there anything that you find challenging about writing songs?

BO: The writing itself—you get the ideas down with pen and paper or in iPhone notes, and you’re looking at them, and you’re like, this conveys a feeling, but it just comes across wrong. You’re like, I couldn’t, that’s not me. That’s not my voice.

So it comes back to what I was saying earlier: wordplay and getting the message across. I find that challenging. Recording is also a big challenge. I probably did the vocals in three takes. There’s a lot going through my head—a lot of pressure in those high-stakes moments, and that’s where a lot of swearing happens. There’s fighting, and a lot of vulnerability.

Our band has a rule: anything that happens in the studio doesn’t count. You don’t count that in the friendship. So if someone calls me a fucking cunt, or vice versa, we leave that in the room. Then we all hang out, and it’s fine. It’s part of the creative process. [laughs]. We need to be violent, focused, and emotional. Recording is a hard part of the writing process because when you record, you sing it, and you’re like, ‘I can’t say this!’ Then suddenly, you’re doing a little edit, adding an extra bit. Or, in the studio, people are like, ‘You should use this word,’ and sometimes I’d be like, ‘No,’ but other times I’d say, ‘You know what?Yes.’

So the writing is still happening during that process. It’s only right when you’re singing it to yourself before it’s even becomes a song. I have songs ready to record right now that I hum the melody to, and I think they’re so catchy, but I’ve never actually recorded them outside my head.

For example,I wrote one recently that’s about how big shoes—heels that fit a bigger foot, like a transperson’s foot—are often ugly. I had the melody [sings] do, do, do, do, do, do, do, do, do. It sounds so corny when I say it, but I wrote it on guitar, and it sounded a little better. I sang the lyrics to my partner, and they were like, ‘That was so bad.’ That cut me. But now that I have a test audience, I’ll keep working on it over the next six months.

Another difficult part of writing is dealing with rejection—when you present something and people are like, ‘I don’t understand what you’re trying to say,’ or ‘I don’t like this topic. You could do better than this topic.’ But sometimes you’re like, ‘But I want to write a song that some weird person would react to, even if it was just one person.’

I like that. What was one of the most sort of emotional moments for you when you were recording?

One song I’m not happy with the the performance, and I went back into a studio of my friends to rerecord it, and I think I might attach it, send it to my mixer, is the song ‘Babe’. I had such a difficult time singing it, because that one song needed more, it’s like, my personality was not enough, and it needed me to sing really clearly on pitch. The chords, everything was pulling you into like this pitch, and it’s this rocky, slow, melodic, tight of jam. I had to do that a thousand times! When we got it back, I had to auto tune and pitch correct so many parts of my vocal delivery, because it sounded bad if it was a little flat or a little sharp or a little yell-y.

That was so emotional because it was devastating to realise, this song isn’t working, but we had recorded it. What do we do? So I went back into another studio and recorded another version, trying to throw the original out the window. If it doesn’t work, I don’t know what to do with that song, because it just feels like it isn’t connecting.

In the studio, doing try after try, with people saying, ‘You can’t sing it,’ that was quite emotional because I want to be a good singer.

Did you ever think you’d be a singer?

BO: Yes.

When did you first know that was what you wanted to do?

BO: When I bought those CDs that I spoke of earlier, like the The Mamas & the Papas, and I would sing along to them. I would tell everyone, ‘I want to be a singer.’ And everyone knows that I can’t sing one key [laughs]. My whole family is always like, ‘You’re okay.’ I would belt out songs in the living room. I would learn lyrics; I’m very good at remembering long streams of lyrics. So I always knew I would be one.

I’ve tried and tried for years, and I always told people I was tone deaf. Then in Berlin, I got a singing teacher who was an opera singer.

Awesome!

BO: She taught me a lot about breathing from my diaphragm, singing in key, and gave me a lot of tips for staying in key, like remembering the notes as numbers and mixing those numbers up. That way, you learn the position of the notes.

I developed a lot more just from those lessons and her encouragement. She had a great understanding that you can copy Patti Smith, you can do the New York Dolls, or you can sing like Bessie Smith and try to be more belt-y. But those people, when they get older, lose their voice because your voice is an instrument. It’s like a boxer, someone who’s constantly putting their body in the fray of damage.

So, it’s a choice. If you want to just be a punk singer and scream, scream, scream your whole life, your career might only last 20 years. But she was trying to encourage me to learn more technique to sustain longevity.

Once I got that skill, I became more critical of how I deliver. But I don’t get vocal fatigue after shows anymore. Still, I can’t always sing on pitch all the time.

It sounds pretty good from where I’m standing.

BO: Oh, thank you. I can hit it better than ever. By the third album, it’s going to be even better and better and better. I have no doubt. But that ‘Babe’ song, it’s a challenge. It’s a cover by a very little known artist from the 70s.

When I heard the original, it’s this folk song, and he has a kind of similar voice to me—he sings a little high and nasally. He’s an outsider, freak-folk person, and I love a lot of independent releases from the 60s and 70s. I loved it! I was like, oh my God, the chorus! I would love to sing this.

It’s hard to say why someone like Bette Midler or Helen Merrill or any jazz singer would choose a specific song to cover. You hear it, and you’re like, I feel like I could do something interesting with this. I did add one verse myself. It’s simple, heartfelt, sweet, and also a little cool. I was drawn to it. Our version doesn’t sound much like the original, except for the chords.

But my band doesn’t like playing it live, so we don’t do it. They don’t really like the song. No one really likes the song! [laughs]. So, grappling with that is still an ongoing issue.

Everyone in your band seems so strongly individualistic, which is really refreshing to see, especially live.

BO: Everyone’s very independent. We’re all encouraging each other to do our own thing, but we are just that, there’s no fake put on. We’re in a flow state at this point because we know what we’re doing and it’s just—FUN!

I feel like you’re really hitting your stride. I’m excited for you to put this album out into the world. I sense that bigger things are on the horizon.

BO: I feel like something is coming, and I can just feel it in the air myself, too. Usually, when I say things like that, I pinch my arm until it bruises because that’s my spiritual side trying to tell me not to be audacious or gloat, or I’ll ruin it. It’s a superstition I have. And, I don’t feel like pinching myself at the moment. I feel like flowing with an accepting love. I know something great is going to happen! I’m ready.

Follow: @br3nna_o and @dinosaurcityrecords.