Titled after a track on The Saints’ classic second album Eternally Yours, Naarm/ Melbourne author and musician, Tristan Clark’s books: Orstralia: A Punk History 1974–1989 and Orstralia: A Punk History 1990–1999 narrate the evolution of Australian punk from its underground inception in the ’70s and the emergence of hardcore in the ’80s to its commercial ascent in the ’90s. Clark’s comprehensive volumes delve beyond the music, exploring cultural and sociological contexts. Enriched with interviews from an extensive list of artists including The Saints, Radio Birdman, Boys Next Door/Birthday Party, Babeez/News, Victims, Leftovers, Fun Things, Zero, Psycho Surgeons, X, Depression, Hard-Ons, pioneering all-female artists Gash and the Mothers, Cosmic Psychos, Grong Grong, The Living End, Bodyjar, Frenzal Rhomb, and many more. The story is covered city-by-city, as well as significant regional centres, providing an unprecedented account of Australian punk history.

Gimmie spoke to Tristan about his 8-year-in-the-making project, how he used his discontent from a customer service job to start the project, his punk rock origins, and of the tragedy and triumphs he documented of the people that create Australian punk.

You’ve been involved in the Australian punk community for about 30 years. Your books, Orstralia: A Punk History 1974 – 1989 and Orstralia: A Punk History 1990-1999 are about to be released; how are you feeling?

TRISTAN CLARK: I’d like to say relief; it’s been such a lengthy process. It’s still hard to fathom that it will be out there. There are still all manner of things to do around it: I have to post a lot of stuff. I guess the perception is, ‘All done, it’s out,’ but there’s still a lot to do. It was probably approaching eight years from when I first started the book till its release. Admittedly, I finished writing it quite a while ago, but I was just waiting for it to get published. It was a glacial pace, almost probably worse than releasing punk records.

How did you first discover punk?

TC: I saw a skate film called Gleaming The Cube (1989). There’s a scene where he [Christian Slater as Brian Kelly, a 16-year-old skateboarder] puts on headphones and it’s D.R.I. playing. You know what D.R.I. are, such an intense experience. I had no frame of reference for it at the time. It was kind of terrifying, yet simultaneously alluring. Back then, obviously, you didn’t have the means of identifying and procuring that kind of music. So it passed me by.

A few years later, a friend acquired a tape, someone had passed on to him on the bus at school and then in turn he passed it on to me. Immediately, I could connect it back to that music that I’d heard previously. On that tape I recall first hearing Poison Idea ‘Feel The Darkness’. Needless to say that led me down a, an unforeseen dark path, pardon the pun.

Have you always sort of lived in Naam/Melbourne?

TC: I was born in Tasmania, but we moved here when I was six. My recollections are all pretty much Melbourne.

What were you like growing up?

TC: I was a pretty introverted, quiet kid. As to how I developed an interest in punk music, that’s a pretty uninteresting one. My upbringing was largely suburban middle-class normalcy, so there’s nothing notable to speak of. It was all good family, sports, and a good school. A lot of underage drinking, which later lent itself to punk. But I was kind of wary of the traditional life patterns that I was seeing around me. There was some sort of internal urge to break from that. I didn’t have a clear vision of why, but I was always aware that I was a bit different, internally, from most of the people I knew. I was also lucky in that, I didn’t struggle socially at school. That difference over the years has probably seen me perceived as a little snobbish at times. Really it was an awkwardness and introversion, which I came to realise later that’s quite pervasive amongst punks.

How did you find your local scene?

TC: I was pretty fortunate in that a kid at school, he was either playing in a band or he was really attuned to what was going on and he would put up fliers around the school. There was a noted all-ages venue that was close to where we lived that was part of the circuit touring bands or even international bands would play. I saw Fugazi, NOFX, and Propagandhi there. There was a big all-ages scene at that time really thriving, it went deep into the suburbs. There’d be 100s of kids attending shows in suburban halls. It was also very unregulated back then, which made it even more enjoyable. This was from ’92 onwards.

There’s some younger bands at the moment that are making a real conscious effort to put on all-ages shows. In Melbourne, given that we have a huge scene here, there’s always been a conscious desire to put on shows away from licensed venues, there’s a consistent history of shows in unconventional spaces, like under bridges and in disused buildings. There was one put on a couple of years ago in a tall office block right on Southbank overlooking the city. We’re sitting in this plush boardroom with our feet up on the desks. It was quite incredible till the cops came shut it down.

I’ve seen video online of some cool shows in Naarm, like the shows Christina Pap from Swab puts on in drains.

There’s been some really incredible ones of those, more often not involving the police as well. They’re just great, that kind of thing, especially as a young person would be so enthralling.

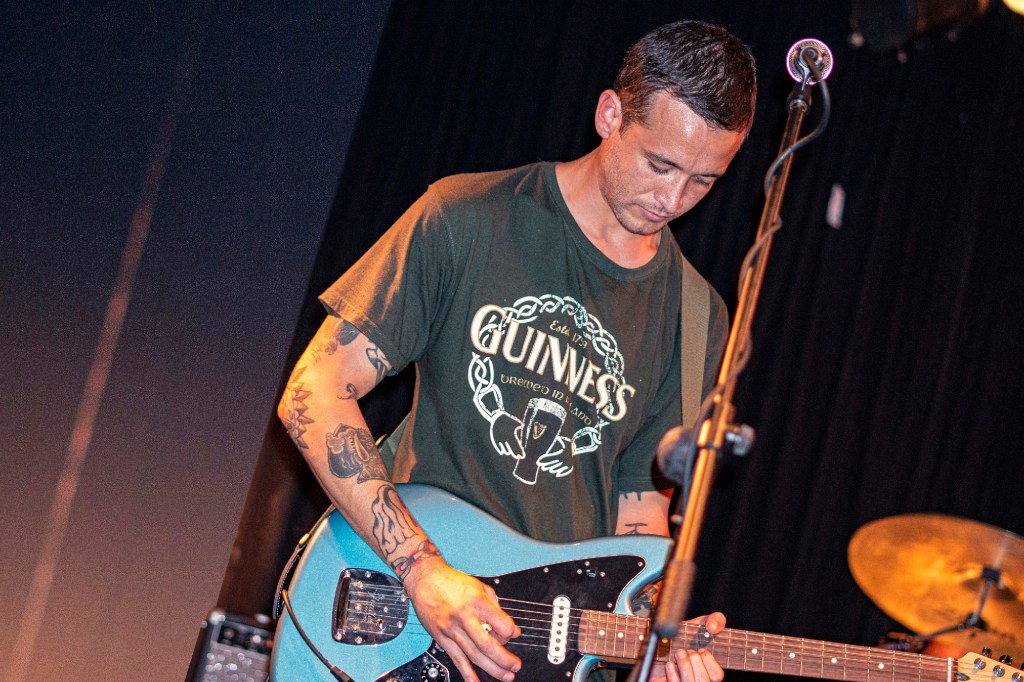

How has punk influenced your life? I know you’ve played in a lot of different bands: Bloody Hammer, Infinite Void, Deconsume, and more. I have some of your records.

TC: These kinds of aspects are just not things that I ponder. It’s interesting. You spend three decades of your life immersed in something without really giving much consideration to what the reason for your motivations are—at least, I don’t.

My background was more in the political scene, really quite explicitly, explicitly political, and that was very much entwined with activism. Therefore, a lot of stuff, even, I have to admit like a lot of zines and writing about punk just seemed of secondary importance to me, like frivolous navel gazing. I was more into dense political reading. As you get older, you get a bit less dogmatic and allow space to investigate these things.

When I was young, following high school, I was studying graphic design. I was promptly kicked out and banned from that. At that stage, I developed this budding political awareness through punk. I saw my future in an advertising agency, which was something that I couldn’t really reconcile with my very undeveloped anti-capitalism views back then. So then I went off to study politics, but that was very quickly subsumed by bands and touring and I dropped out.

Punk has come to permeate every facet of my life. At times I feel like I’m a relic in that still rigidly set in those ideals. I’m not inflexible, but maybe I am [laughs]. I’m still very much interested in politics. I still love the music and frequent shows regularly. My social circle is still primarily punks and my socialising does tend to be shows. There’s not even the thought of going away or pursuing something else. It’s been such a constant and all-encompassing to my life. Especially the last eight years spending every spare moment writing about it.

In the ‘About the Author’ section of your book it says you’re an educator; are you a teacher?

TC: A classroom aid. I work at a non-mainstream high school, a small community high school that’s traditionally attracted a lot of students who would be considered freaks and weirdos. Of course, there’s been numerous punks amongst them. There are kids that have played in bands. It’s interesting that we have a large proportion of students who are neurodivergent. There’s a number of punks amongst them, and it became quite evident to me from this and through my research and interviewing, just how sizeable that segment of people who have been attracted to punk are neurodivergent. But that probably hasn’t really been recognised or acknowledged.

I noticed that reading your books. I remember quotes from Link Meanie talking about mental illness. I had no idea he struggled with that. I learned a lot of new stuff from your book. I think his talking about that will make a lot of people feel seen and maybe not so alone. I think your books are going to start lots of conversations, which is really great.

TC: It was interesting how intimate that interview was. I’ve never met the guy, but we totally revered him as teenagers. It was surprising that a lot of people I’d never met face-to-face, once you get into conversation, how much they were willing to reveal. Really personal, even traumatic stuff at times.

Tragedy is a big theme throughout the book. At times it’s so brutal. Like, when Ed Wreckage from The Leftovers was talking about his band and said a couple of people in the band committed suicide and others died of cancer. Ultimately, Ed passed away before the book came out.

TC: That is definitely one of the overarching themes, sadly. But, you know, as someone like yourself, who’s been around for that long, you’ve seen all that firsthand. I was having a conversation with one of the first punks I ever knew this morning, and we were talking about how many people we know who are dead.

I gave the book to my dad to read before I signed off on the final edits. I was like, ‘Oh, what’d you think?’ His first response was, ‘A lot of dead people.’ That was quite jarring. The other day, I catalogued how many people I interviewed that are now past, I made a post about it to acknowledge those people. It’s a dozen. 12 out of 200, is kind of staggering. I don’t think it’s necessarily exclusive to punk, but they’re not lifestyles that are given to temperance or longevity.

I understand that you got started with your books because you said you were unhappy working a job in customer service and you were kind of looking for some purpose or some meaning.

TC: I was disgruntled with where that side of my life was going. In terms of my creativity or my social life, I couldn’t fault it, but my professional life didn’t really exist. I was working this crushing customer service job. And then I just happened to reread, Inner City Sound by Clinton Walker. It’s a cool book, but it’s very limited in what it documents. Seeing other books from places that were being published, it became evident that there was nothing that could be considered comprehensive that had come out of Australia. There’s a lot of other projects and books from here, but a lot of them tended to consign themselves to a specific place or time or a limited number of bands. I felt there was a glaring gap that someone needed to fill. I saw myself as that idiot that was going to undertake that project [laughs].

People pointed out to me along the way, ‘Oh yeah, you know, so -and -so tried’ or ‘Many people have begun but never saw it through to fruition.’

Congratulations on finishing it! It’s a big achievement. Before you started doing interviews for this book, had you done interviews before?

TC: No. When I started, I really had no formula. It was really spontaneous. It very quickly fell into more of a conversational form, which lent itself to drawing out a lot more of those deeper and intimate responses from people. That was the positive side of it. The negative is, you have to go back and transcribe bloody two hours of tape that you’ve just done, waffling on to each other.

Who was the first interview?

TC: A friend of mine. He played in Thought Criminals in the late-70s. They’re one of the more noted bands of that time. Their record’s quite revered. So then I felt that I could use that as leverage with other people, like, ‘Oh, well I’ve interviewed this band, I’d like to interview you.’ Amazingly people were so forthcoming and placed trust in me. I was a random guy with this big claim that I was going to write this great book! People didn’t really question that, they were willing to offer me their time. I’m forever thankful for that.

What were the things that you were most interested in finding out about from the people you spoke with?

TC: Initially, it was more to do with the band details and minutia but it quickly became evident that wasn’t the interesting aspect. It was more people’s stories. Obviously, you want the humorous anecdotes that will get people to pick it up but I found people’s personal lives were more compelling than often the music itself. People had these really rich lives either adjacent to punk or after punk. I began to really try and capture that aspect.

I remember one interview I did with one of the guys from Last Words, it had gone on for an hour and a half. We got to the end of it and he happened to mention in passing that he was now a pastor. I’m like, ‘Oh, sorry, we’re gonna have to go back and unpack how you get from playing in a punk band in the Western suburbs of Sydney in the late-70s, living in a migrant hostel, to now being a man of the cloth. There’s a lot in-between here that I need to know about.

Any other really memorable stories or even ones that didn’t make it into the book you could share?

TC: You had really polished performers like Jay from Frenzel Rhomb or Russ from Cosmic Psychos, who have honed their interview skills over many years. They have a wealth of anecdotes to humour you with. But often it was the really unassuming ones that you went into with very little detail about their band or their lives and you’d come out of it and just be like, oh wow! That was so rich and fulfilling, or maybe traumatic as well.

I made a conscious effort… bands like The Saints and Birdman, obviously everyone’s heard Ed [Kuepper]’s story, ad nauseam, same with Deniz Tek and Rob Younger, but I made an explicit point of tracking down other members of the bands that could offer a different perspective. I spoke to drummer Ivor Hay. I said to him, ‘Oh, has anyone ever interviewed you?’ He’s like, ‘Outside of the documentary? No. No one’s ever talked to him about the band.’ It’s quite different to that standardised narrative that you get from Ed.

I think that the thing that makes The Saints’ story extraordinary is, when you look at the Ramones and The Damned, you’re talking these great cultural centres of London and New York. Then you talk of the Saints you’re talking about Oxley, that was the most conservative and stifling environment. Their message more spoke to suburban alienation and monotony, and that oppressiveness that was ever-present to people in Brisbane, transgressive or, buck the norm at that time.

Was there anyone that you wanted to find for the book that you couldn’t?

TC: A few people. Especially women it seemed were reluctant to share their stories. I could only speculate whether there’s trauma or an unwillingness to revisit that aspect of their lives. I’m not sure.

I was hoping there would be more women featured in your book, but I do understand the reluctance of women to participate. I wanted to include a lot more women in my own book because there have always been women involved in punk, and I know that there is a feeling that we often get written out of the story. As a woman in punk myself, it’s very, very important, but many I asked didn’t want to speak for it or ignored my request. I wanted to ask you about it because some people may see your book and complain there aren’t enough women, but what they don’t see is how many people you may have asked. It wasn’t through lack of trying on your behalf.

TC: That’s how I feel. Given the extensiveness of my research, I couldn’t uncover too much—it still is uniformly white and male. But then the proportion of women that I did get is reflective of the numbers of performers. Ideally, I would have liked more. I’m scared of that critique. But I did try. My book would probably be close to like 10% women.

I really appreciated all their contributions and the perspective they gave.

TC: For the most part, they were positive. There’s probably periods through the 80s where that real masculinist sort of thing was dominant, especially during the hardcore era.

It’s still that way to a degree. The hardcore scene, more so than the punk scene.

TC: That’s probably not something that I’m too exposed to. But within that more politicised scene that I tend to still be involved with, it’s changed so much and it’s fantastic. There’s always going to be problems, issues, but there’s been a definite attempt to rectify things and people are quite vocal about confronting issues and certain attitudes.

Your books are named after The Saints’ song ‘Orstralia’. When in the process did you realise that was going to be the title?

I originally had the title of Gobbin’ on Life. If you look through the content it seems quite suited, but then I had, especially some older men, questioning it. Even people that weren’t involved in the project were like, ‘Oh, that’s a dumb name.’

It can be scary putting stuff like this out into the world. People love to critique and judge.

TC: I am anticipating some backlash. I had an article in the City Hub the other day and they titled it: The Rise and Fall of Punk. I never made mention of a fall at all. He was an old school journo, he wrote shorthand. When I read the feature I felt sick. That’s not what I said. No, no. And then I stopped reading it. I thought that hopefully no one will see it, and then some people started sharing it on the internet. I guess I’m just going to have to live with it.

Are there any punk books that have made an impact on you?

TC: A lot of books are strictly oral histories. They’re still fascinating and have great anecdotes, but they then tend to lack context. I really wanted to sort of be able to place punk within its political and social and economic context within Australia.

I’ve read a few books, John Savage’s England’s Dreaming, that’s the classic. But beyond that, not a lot of them. I probably read, Please Kill Me years ago. I was always more into political writing.

I really liked that your book went beyond the major cities scenes and bands.

TC: That was a very conscious effort to do so. It is hard to excavate that history from outside the city centres. It took quite a bit of effort, but if I was trying to tout something as a comprehensive history, I had to do that. It was fascinating to hear about bands that never amounted to much in a conventional sense. A lot of them only ever played a small number of faltering shows, but they had some great stories that accompanied them.

I tracked down The Rejects who were the first punk band in Rockhampton in the late-70s. They were staggered that someone knew about them, let alone wanted to ask them some questions. They played one show ever at their high school graduation.

I noticed at the beginning of your book, in the preface, you said that some of the views expressed in the book don’t necessarily align with your own values. Reading through the book I was alarmed to come across the views of a particular band from Western Australia.

TC: Yeah.

Was it hard to sit there and hear these things during an interview?

TC: I didn’t actually give him any allowance to express any sort of repugnant views. I really stuck to the music, but he’s still, as far as I’m aware, a neo-Nazi.

People probably, they’ll find that contentious that I included people like that. You know, there are a couple of neo-Nazis that I interviewed or former neo-Nazis, and people will find that problematic. But I’m like, well, I don’t want to hide all these distasteful aspects of punk, I think I have to include it. Perhaps that requires me to speak to people that I never would otherwise – I find their views horrifying – to give the full picture. But yeah, that was a pretty interesting one. We did the interview and nothing distasteful was said and it was polite enough, but then he said, ‘Oh, the guitarist in my current band is now living in Melbourne. You should like meet up with him.’ And I was just really evasive, ‘Yeah, yeah, sure.’ Then he keeps calling me. I do’t want him to think somehow that we’re friends or maybe that I have some sort of sympathy to his views. I’m really polite. I’m not going to be like, ‘Fuck off.’ Eventually I stopped answering and that was the end of the correspondence, thankfully.

There’s people in the book that I included that I’m aware of things that they’ve perpetrated that makes me feel really uncomfortable, and especially uncomfortable meeting them in-person or speaking to them. I had to put that part aside, just say, ‘Look, this is your purpose, to try and glean information from them, to give a fuller sort of history.’ There’s a difficulty in that when I know what you’ve done in your past. Like, with the singer from Bastard Squad. I’m kind of scared that what I’ve written, not that I wrote anything that isn’t true in there, you know, most of that, aside from killing his girlfriend; he didn’t want to talk about that. But there’s a lot of sort of unsavoury elements in his life.

One thing about making the book… it’s interesting how people can oscillate between extremities, like especially people that, you know, found themselves as neo-Nazis and then could have sort of this ‘Road to Damascus’ moment and atone for that by then turning into ardent pacifist anarchists. And that they’re able to somehow make that switch. It’s like the same energy, but the opposite way. Like I said, my thinking is still fairly rigid and very much sort of in line with what it was 20 odd years ago.

Is there anything you learnt about yourself throughout the whole process?

TC: Probably more so the aspect about the neurodivergence, but that also coincided with my job as well that I started working. I was like, oh, you know, these certain things resonate with my own behaviours as well. But, beyond that, no, I’m not sure. Maybe I guess a patience and resilience that I wasn’t aware that I had. I felt at times that I was doing what was almost effectively informal counselling for some of people.

I’ve gone into a role at work where you take on this wellbeing role. So whether you know that ability to sort of sit and listen to people and really empathise with them. Maybe that in part really honed by interviewing so many damn people and listening to the often troubling stories and thoughts.

Anything else you want people to know about your book?

TC: I guess, weirdly, it feels like maybe some sort of semblance of reflection on it, and this might sound contrived, but it almost feels like an offering to the people and scene that’s given me so much.

I’ve speculated so many times about, what my trajectory might have been if I stayed that suburban stoner kid. I can’t imagine it to have been a tenth of the experiences I’ve got to enjoy because of punk.

Punk, it’s permeated, fashion, art, more mainstream music, that’s undeniable. It’s imprint on Australian culture is surprisingly much larger than what you would think for something that has mostly being fairly marginal, aside from brief periods of sort of prominence. It’s something that’s probably not been duly acknowledged.

Buy the books at PM Press (worldwide) or from Orstralia (Australia).