This year Chapter Music released The Job which is a collection of lost recordings from between 1979-83 of Melbourne post-punk-disco-funk band, Use No Hooks. We spoke to UNH bandleader Mick Earls to get an insight into the band and that era of the Melbourne music scene. They were part of the experimental Little Band Scene. UNH were pioneers and rule breakers, it’s no surprise their music has stood the test of time to finally become revered today.

We’re really big fans of your band Use No Hooks! The album – The Job – of previously unreleased recordings that Chapter Music released this year is really ace!

MICK EARLS: Thank you. Can I ask you what it is that you like about it?

Of course! There’s so much. I really love punk rock but then I really love people that take it further, like what Use No Hooks do. It’s almost like your music has no rules and that there is a real freedom on the record. If you think back to the time period that you made it in and what else was going on, you realise that what you were doing was very different back then as well as even now. The lyrical content is still relevant now too.

ME: Well, thanks a lot! You’ve made a couple of really perceptive observations there about the freedom of it. You mentioned punk and you mentioned taking it a bit further, doing the best I can to think back to what we were thinking then, if you play that record to a lot of people who have a certain idea of what punk was they would think there is no connection because it doesn’t sound like the [Sex] Pistols. What we thought punk did was clear the ground for pop music to start again from scratch, it wasn’t just a new musical style, category or genre; it made it possible for literally anyone again to start playing music without any preconceptions of what they ought to be capable of or what was expected of them.

Fairly soon punk started to think of itself as a particular image and style, which is perhaps modelled on the British bands or American bands like the Ramones, or even going back into the Velvets a bit, these were models for new artists to aspire to, once it started to think of itself in that way it started to lose contact with that enabling idea—that music can start again from scratch. What became post-punk took up that idea and recovered that enabling idea, without feeling obligated to sound like punk. It was quite the contrary to go right away from it while still honouring the aesthetic. That aesthetic was put to work in many ways on many fronts during that period of ’78 to roughly ’84 in inner Melbourne and Sydney too.

In Melbourne it was still really quite a small scene and there wouldn’t have been more than a couple of hundred people who were aware of this and attending gigs and playing in the bands. It was very vibrant! There was certainly a freedom about it. Audiences had had their ears blasted off and they were kind of ready for something that might extend their sensibilities beyond what punk had done, and beyond what punk had wiped away to some extent. There was almost a clear horizon, where people were prepared to accept anything. We were one of those bands together with the Primitive Calculators, with that idea of starting from scratch without preconceptions and musical training. It’s not really a new idea though. If you for instance listen to the early Johnny Cash records in the ‘50s, he and his co-musicians could barely play their instruments but they did it in a way that was unprecedented, very distinctive and completely compelling; they did what they could with what they had without any vision of where it might lead them in the end. That’s the kind of things we were doing with the ‘Calculators.

It must have been an exciting time!

ME: Yes, there was a real sense that anything is possible. Myself and Arne Hanna got Use No Hooks going with drummer Steve Bourke. We all had sufficient musical experience and knowledge, we weren’t punks or starting off having played for five minutes. We knew quite a bit more than three chords and a beat. We were able to draw on that idea of starting again and to do it in a way anything was possible. We could pull in a really eclectic mix of elements coming from different music like surf, soul, electronic drone music, American minimalism and jazz, which had been taboo during the punk period. There was also disco and eventually the funk and rap that ended up on this LP.

The three of us got going with very minimal approaches to things. We would do things like bring in tape recorders with pre-recorded sound on them like, the TV and news broadcasts, which we would operate through reel-to-reel tape recorders—we were sampling it effectively. Our first band was called Sample Only, that’s what we were doing before we even knew we were doing it [laughs]. This was the kind of experimental process we took but then we started adding more players and changing players. We pretty much devised new material for every gig; a lot of it worked, a lot of it didn’t. There were long-form compositions with blending different elements usually over some kind of pumping beat in parts, then it would drift away into other things. Every now and again we would craft some songs. We had a singer and that singer might disappear [laughs] and if somebody else came along and offered themselves we would usually bring them in in some way or another; that’s what I meant by anything is possible.

You can hear some of that material on the digital downloads that came with this LP, some of the early material. Not so much the audio-collage drone music stuff though, the audio quality isn’t good enough to be included. We had to patch the stuff up quite a lot.

It wasn’t until the final phase of the band, which is the phase that produced the material on this album, that we had anything like a regular set-list and even probably formed songs. It was still experimental, in the sense that I had never written rap lyrics before; I just came up with a whole heap of almost clichés, familiar expressions you’d hear around worksites and hearing people in the media talk about work or politics and so on, that’s where I drew all that from. I thought of rap as a sort of rhyming machine.

At the time we had been playing these long soul, funk, disco grooves with a four-piece. After our singer Cathy Hopkins left, and our saxophone player at the time Michael Charles left, we just decided to bunker down and try to play long grooves that were danceable. We all loved American funk. We acquired a fabulous bass player called Andre Schuster who could play in that style, like the band Chic for instance. Steve the drummer left and Arne switched to drums because we wanted a more basic drumming style with steady beats and good solid tempos, which he could do without having prior experience as a drummer. Here we were on the punk idea—just do the best you can with what you’ve got!

Hearing that material now for me, after all these years, that’s what I notice the most, the drumming on that record. I notice it more than the vocals or guitar and even the bass playing, it’s just done so right. We ended up playing that material without any idea of where it would go but it started to acquire a bit of a following and we started to play outside of the smaller venues and inner city pubs where we had played previously.

The excitement was there! It was also right outside the music industry. There was no sense that we should build up a following and make ourselves famous and get on Countdown. We had no idea what we were doing but, it seemed to work and here we are! [laughs].

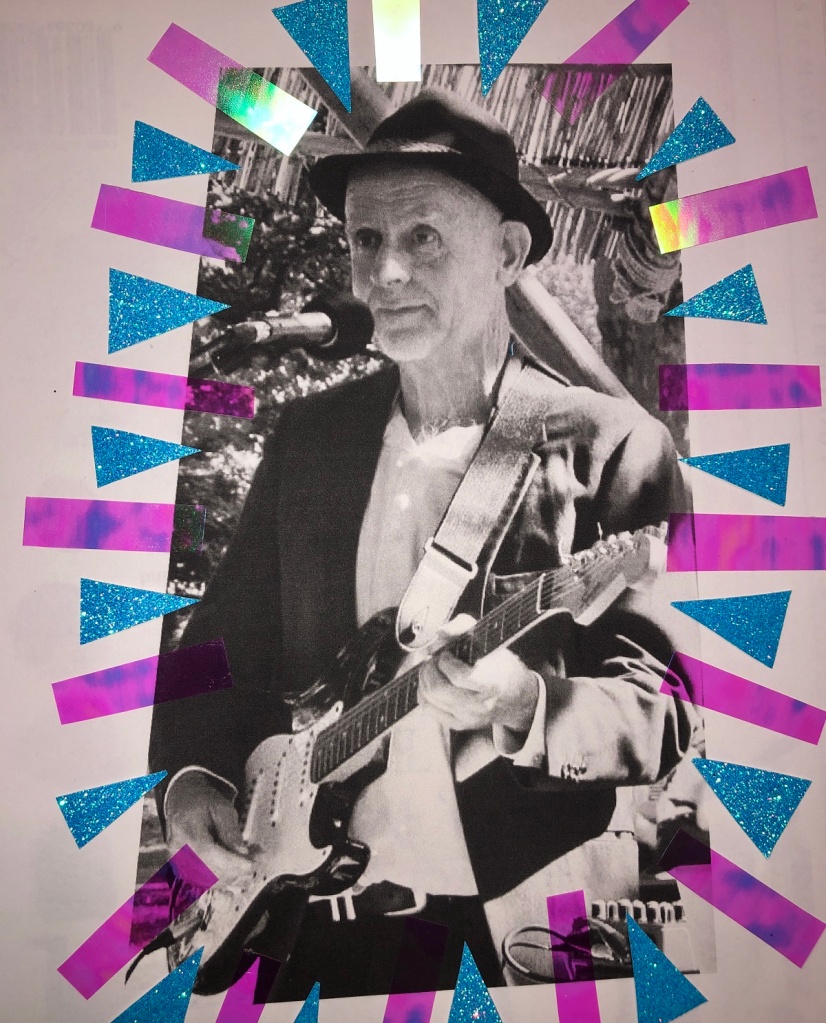

What first inspired you to pick up a guitar?

ME: This was when I was a kid when I was really young, I’m a bit older than most of the others involved in this, I heard guitar music in the 1950s. In those days there was a lot of instrumental music on the radio in the Pop Charts. Duane Eddy was an American guitarist and theme from Peter Gunn was his big hit and then there was an Australian guitarist called Rob E. G. and then there was The Shadows and the surf bands and groups and the rock n roll guitars like the Elvis Presley records. I had an older cousin that looked like a rocker and had an electric guitar… and then along came The Beatles and so on, which almost became obligatory if you were interested in music to start playing guitar. You could get guitars relatively cheaply and bang away without really needing any sort of tuition. There were books, I basically just learnt out of books and just strumming away in my teenage bedroom [laughs].

I read that in the mid-1970s you were exposed to non-narrative experimental films at the Melbourne Filmmakers Co-op in Carlton; did that influence your creativity?

ME: Yeah, oh yeah! I did! It’s a bit of a personal idiosyncrasy in a way, I was exploring anything that was outside the cultural mainstream at the time, there was a lot going on. In Melbourne there was the Carlton Filmmakers Co-operative and they use to screen a lot of that stuff but there was also a place in Flemington called The New Music Centre, which was a government funded facility in an old church. It was mainly run by electronic and experimental composers coming from the classical music tradition and sound poets and people like that there.

Around the same time I also attended something that was a festival of tape music, music that was composed purely for recording. That was in a run-down factory space, behind the Filmmakers Co-op. I was also interested in writing, I was interested in contemporary literature and poetry. I was open to almost anything! These ideas got into how we compose music. You wouldn’t necessarily start off with an idea of beginning, middle and end, and a progression to get from a verse to a chorus to a pre-chorus; we didn’t bother with those ideas so much.

The non-narrative film style that really caught my attention was the minimalist style using repeating images. There was an Australia filmmaker called Paul Winkler whose films I saw quite a lot of. He would have maybe an image of a brick wall with almost a jackhammer kind of sound going, filmed through a handheld camera that would be shaking back and forwards in time with the jackhammer sound—that synchronised sound and music. You couldn’t take a real lot of it but, it had a very powerful affect. This is what I first thought of when I saw The Primitive Calculators play. It was very much small repeating cels of music played with a lot of distortion and a relentless drive coming from the drum machine.

Experiences of seeing those early films gave me a bit of a sensibility that enabled me to appreciate some of the things I was hearing the punk bands do, even though I was never going to be a punk player myself. I was very appreciative of it though and that’s what went in to Use No Hooks a bit. We used noise occasionally but also the aesthetic of minimalist repetition was something that underlaid most things we did from the earliest to the funk period. We realised that the idea of minimalist repetition could be taken and just applied to different music material, soul beats (which we did in the earlier stages), then disco beats (which we used much later). We’d make up rhythmic parts that would interact and repeat in a way that might be sustainable indefinitely. These were the ideas that went into what we were doing.

Improvisation and experimentation are very important parts of Use No Hooks’ way of doing things; why was this important to you?

ME: Part of this was political, politically inspired, because this was a period it almost seems impossible to imagine now but, very large numbers of people, young people especially, thought that there was some prospect of a major revolution in the Western world. Not in the sense of the Soviet Revolution but something where people could take charge of their own lives to some extent and build some kind of new society that couldn’t be programmed, I suppose. These ideas were very prevalent at the time and very influential and very powerful. People in the Arts in general were pretty much seized by them. The experimentation in a way you could see, was sort of an attempt at modelling how a new world could be constructed. A new society could be constructed from first principles which is what people across the Arts were doing. I’d say that perhaps might help give some understanding of why we felt driven to do this rather than to follow the accepted path of working out of a particular style, or format an image you wanted to follow and getting a manager and trying to promote it through the industry; it’s not what we were remotely interested in doing. The Primitive Calculators too! There were a lot of people in the punk scene that were interested in those ideas! An element of despair had kind of come in by that stage though, it’s not going to happen so we’re angry just the same.

Is there a Use No Hooks song that has a real significance to you?

ME: Not really. There are some I like more than others for the groove really. The ones that have significance for me personally are more of the earlier material, some stuff that didn’t make it on to the record or download. Lyrically, see none of it really has personal significance because all of the material, the rap-based stuff, is all impersonal; they’re all bits of language expression that have come from elsewhere, that have come out of common usage. That was the idea at the time, I wasn’t going to try to write about personal experience or values or so on, that comes through to certain extent in the irony that infuse all of those lyrics.

The track I’m most pleased with lyrically is “In The Clear”. There’s an emotional tenor in those lyrics that I like. There’s a humour. The humour that’s in it all seems to work pretty well. In terms of the groove, the music, “The Hook” is the one I like best. That nice bassline of Andre Schuster! The bluesy, slightly dirty harmonic element in it!

I understand that in 1984 Use No Hooks took a bit of a break because you were going to write new material; what kind of stuff were you writing then?

ME: Yep. Arne and I had decided that we wanted to get into Afrobeat, the music of Fela Kuti was something that we both were taken by. I first heard of a Fela Kuti record in 1971 and gathered quite a few recordings over the next ten years or so, and they influenced us a real lot. We didn’t really have the technical capabilities to compose that sort of music. We wanted to get into it partly because the stuff that we were doing on the record wasn’t working so well in live performance for various reasons. We thought if we got into more Afrobeat stuff… music on the record was pretty much put together in layers and sometimes that wouldn’t work live, if the tempo wasn’t right the song wouldn’t work, this was a problem we were having… because we didn’t pay attention to foldback and couldn’t hear ourselves on stage. We thought if we could compose music that had more interlocking parts where all the various rhythmic components leaned against each other or sat in each other’s space a lot more it would work better. Then we discover we didn’t have the technical expertise to do that. Then I had to get a job.

I had a very high-powered job and others went off to do other things. It just sort of died and never got back together. Although Arne Hanna went to Sydney and did a music degree and computer technology degree. He got into Afrobeat music big time and had a couple of bands of his own playing that music. He also then became a mainstay of the Sydney jazz scene as a guitarist doing session work for people, and also as a producer.

Finally after Arne and I got back together in 2016, I hadn’t played music really since 1984, he’d acquired the necessary expertise to compose in that style… we’ve since done a bit of work using those ideas, plus more sophisticated musical ideas that come out of Latin music and funk. That’s what become of that particular band.

Will you be putting out any of the newer stuff?

ME: We’re working in it! We did a few gigs as a duo, using computerised backing tracks, pretty much all new material. Some of the old things we re-worked pretty quickly to get them ready for gigs. They sound quite different, you wouldn’t think it was the same people. I’ve been doing the vocals and I don’t sound like Stuart Grant [also frontman for Primitive Calculators] who’s on the record, I’d never done them before! The experimental approach continues! [laughs].

There are recordings of one of the gigs that could partly be released in time. We are thinking about getting around to posting up some of these tracks plus some of the early material. We have other things in our lives and getting around to doing that stuff takes time. We hope to be able to. Arne and I are working on some tracks we’ve recorded sections for. There’s a fair bit in the works!

What was it like for you to do vocals for the first time?

ME: Look, I found it strangely relaxing if you would believe. I never enjoyed performing, I was always too nervous and too introverted. To come back now, virtually as an old man, and start doing vocals, particularly with writing new material, I found it really helped in light of performance. It was completely unexpected. Vocalising those raps, I’m not a singer and I don’t sing anything in tune [laughs] but to recite rap lyrics I found it relaxing in the sense that you have so many syllables say to fit a bar or two bars, and it’s a bit like rhythmic improvisation, you can put those syllables where you like but you have to get them out. You’re concentrating on the next word like; where am I going to break this or put it? You do it and then it’s gone and you’re on to the next and then the next. You’re fully concentrating on what’s coming in much the way that would a guitar solo or something. You’re less concerned with; how am I feeling? Am I nervous? Can I do this? What are they thinking out there? How is this sounding? All of these things that go through live musicians heads and that can really get in the way of enjoying the experience of playing. That was a most unexpected discovery, quite weird in a way because I thought, there’s a lot of gall involved with me pretending to do this! Somebody my age getting up on stage and out comes these words! It seems preposterous. Someone had to do it though. Arne can actually sing and sing well but he didn’t want to do it in this case. He was too preoccupied with managing the computing side of things. He played guitar on some of these gigs. He would interject with singing when he had to, when I was reciting these lines. It was good to get a response out of him when performing. It was an unexpected, enjoyable discovery.

That’s so wonderful to hear.

ME: The other thing that some people who have heard these recordings of live gigs said was “Your age has helped give you a slight huskiness in your voice and it suits the lyric and material”. The strange paradox of it all is a lot of people work and work at the craft of singing and vocalising and all I did was get old! [laughs].

You mentioned that you stopped playing music in 1984 and you didn’t start up again until 2016; during that time did you miss it?

ME: No. I didn’t. It ended badly for me really. I wasn’t really happy with how things were going and where it might go. There were a lot of personal issues that came up, which just led me to think that I didn’t want to be part of it anymore. I was working full-time. I went and worked on Smash Hits magazine, which had just started up here. It had been going in England for a couple of decades and then I was part of a team that got an Australian edition started in 1984. I was running production on that. It was a huge, very stressful thing and didn’t leave time for much else. Then my guitar got stolen and that finished things off.

I never stopped listening to music. I got right into classical music, which I never done so much before. I found it such a rewarding thing to do, particularly 20th Century composition, then went backwards from there. I’d always listened outside of the box; for me that was out of the box at that stage. Then I expanded my collection of Afrobeat music and got into Washington Funk of the mid-‘80s, the Go Go scene like Chuck Brown & the Soul Searchers and Trouble Funk, those influences stayed with Arne and I and found their way in to the newer material. I didn’t miss music.

Then I had a problem with my hand. Because I’d never been trained to play guitar properly, I never really had the right posture and I almost ended up with my fret board hand pretty much crippled! Dupuytren’s contracture, it’s a condition that involves a calcification of the tendons. The hand curls up. I had to have an operation on it to have it straightened, which meant that I’m left with hand that doesn’t have the strength it did originally. I thought I’d never play guitar again but when Arne and I started up, I had to play again. I can’t finger the fret board with same dexterity that I could before. I’m limited to mainly rhythm playing. There’s certainly nothing wrong with my right arm, I can still play rhythms reasonably well. I can’t do that much with the left-hand, I had to invent a new approach. I hit certain combinations of strings and move the hand around minimally between complex chords and play parts of them. I’ve got around it in that way and it’s still enjoyable but it’s prevented me from ever becoming a proper guitarist again like I was. That was a sad consequence of the early years, we did a lot of playing. Quite often I’d play for hours on end and be in pain but I thought it was part of it but I ended up stuffing my hand up!

I’m sure now playing guitar in your own way because of your hand, you can play stuff in a way that other people can’t. I believe that if you play guitar, you’re guitarist.

ME: [Laughs] Yes, point taken. I suppose I’m comparing myself to myself and how I was. As a guitarist I was the only guitarist and in some ways, not so much on that record but the early stuff, the guitar is quite prominent and I’m playing with a delicacy and speed that I couldn’t replicate now.

It’s a new guitar playing you!

ME: I guess I have made some advances! I’ve always been an experimenter, and I guess I can play in a way that’s appropriate for what we’re playing now.

I’m excited for new stuff!

ME: Thanks so much!

Why is music important to you?

ME: I’ve read a lot and thought a lot about music aesthetics, I’ve read a lot of philosophers’ writings on music which I could dip into but, that doesn’t get to what attracted me to it in the first place and before I had any theoretical perspective on it. What’s kept me listening to music constantly is its capacity to put you in a certain mood and ability to enable you to constantly modify those moods to what your desires might be or your needs might be in some cases. People that listen to a lot of music, particularly different sorts of music, know that if you’re in a really rotten mood there’s music you can put on that will most likely get you out of it. Alternatively if you’re feeling a bit flippant and light-hearted, frivolous, and you want to hear something more substantial, you know where to go to get that. This is something I learnt at a young age, that there’s a whole universe or feeling that can be generated through music. If you hear enough of it often enough you carry it with you internally without need to actually be hearing it through device, that’s been the experience of my life. There’s often some music that will come up in my head that suits the occasion I’m in, or even provides some sort of commentary on it. It can do that in a way that visual and verbal media can’t. It does it at such a basic level even babies seem to have an instinctive understanding of this; music makes me happy, if you take it away I feel unhappy and I want to hear more. Once you realise it’s actually possible for you to play some of this yourself, you’re on a bit of a road that you know other people are going to hear it and then you have a bit of a capacity to put them in certain moods.

Then there’s a technical element of music, because it happens in time you can put sounds together in a certain order and see where it leads to construct patterns and structures and things and combine elements—it’s a very, very intriguing, engaging process. You can never be sure of the outcome because it’s happening in time and there’s a compulsion to keep doing it. If you can do it well enough and you’re aware of your limitations and work within what you’re capable it can be really satisfying.

Anything else you’d like to share with us?

ME: I think I’ve said enough but, I am fascinated and amazed with the interest that’s been shown for our music now. We never paid much attention to recording and putting out records then, these recordings on the record were done at a practice session in a single take. There was also a fellow Alan Bamford, who is not long deceased, he came to all of our gigs and recorded them all. We weren’t so interested and didn’t want to hear them but Alan had the foresight to realise that in years to come someone might be interested in this stuff. It’s intriguing to think why people of your generation is interested in this music.

Maybe part of is that… if you look at a lot of music now, everyone records themselves at home, very lo-fi and maybe in one take, and they make the most of what they have, they aren’t trained musicians, and it’s the rawness that they can relate to.

ME: The idea that it’s being pulled together in a way.

And it comes back to the no rules and doing things how you wanted without caring for commercial success. Lots of musicians Gimmie talks to don’t care about being popular of famous, they just love making music with their friends and making art for art’s sake. AND I’m sure people like it because it’s just a really, really cool record—that infinite groove! It makes me so happy and it makes me want to dance, it simply moves me!

ME: That’s a really pleasing thing to hear. If something makes you happy, that’s the highest praise really.

Your record also gets one thinking about the endless possibilities in music.

ME: That’s even more gratifying to hear. I think the female voices in there has some appeal too, they’re not trained, you’re not listening to The Pointer Sisters or anything [laughs]. Hearing them gets you thinking that, I could do that! That could be me!

Please check out USE NO HOOKS; The Job out now on CHAPTER MUSIC.